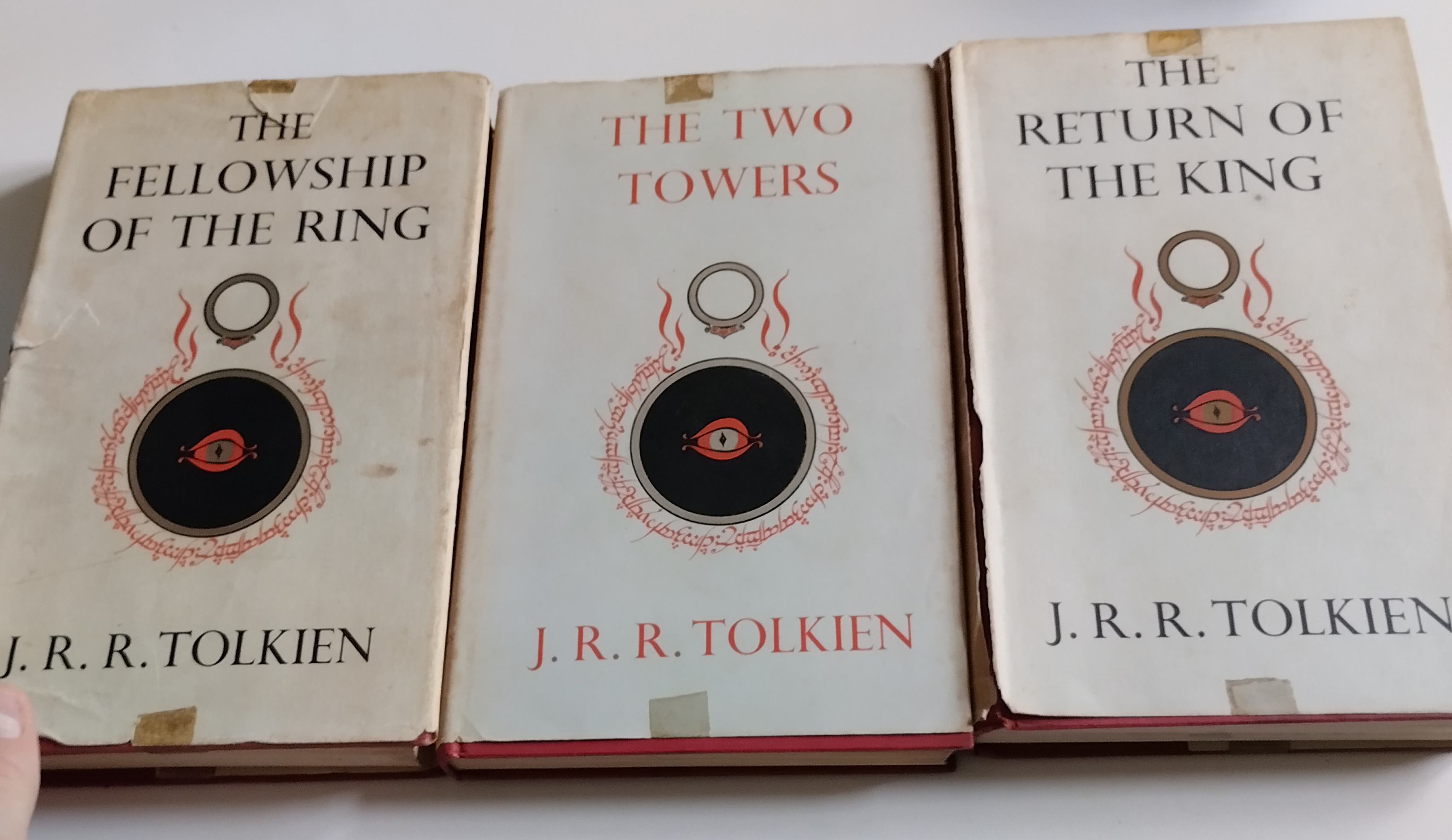

Lord of the Rings is intended as a single book, but it was split into three by the publisher. Its final volume, The Return of the King, released on October 20th, 1955.

It'd be fun to read forum impressions from 1955 of people experiencing it for the first time, but alas that is not possible. However, we can read C.S. Lewis's essay about it two days after its release.

Wonderfully stated by Mr. Lewis.

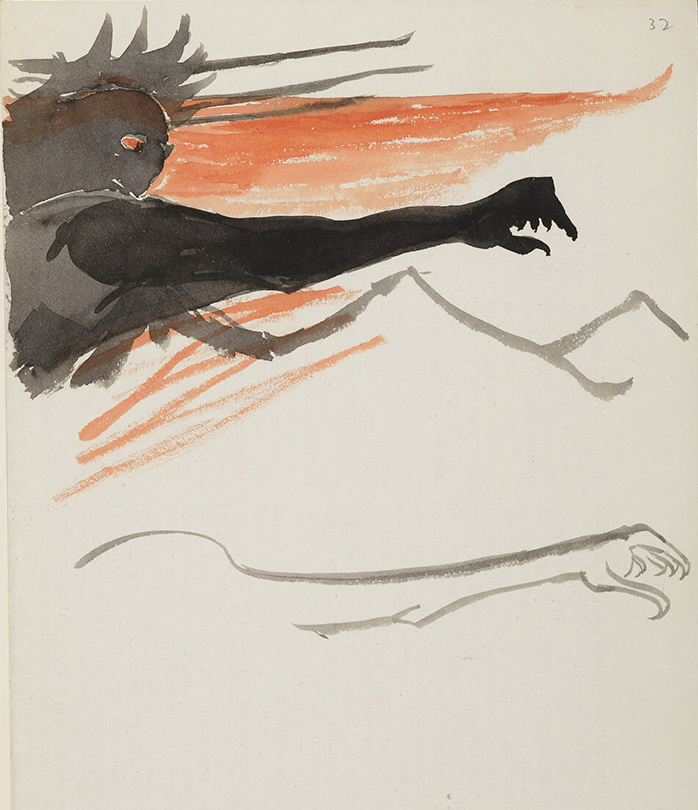

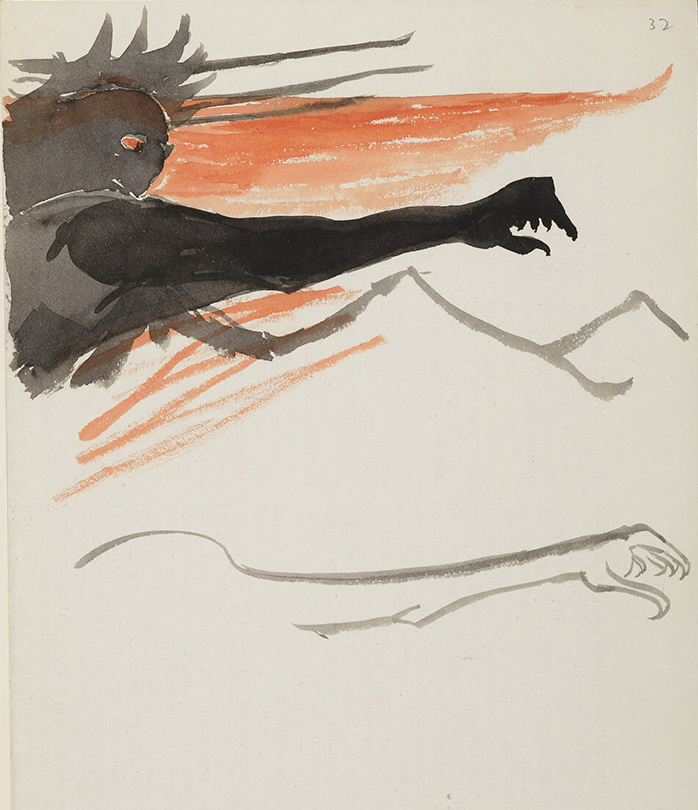

(Tolkien's watercolor sketch of Sauron)

On the other side of the pond, we have W.H. Auden's review for the New York Times. Quite the interesting read, as he describes how LotR was received in high brow, elitist circles at the time, and with some keen insight into good and evil:

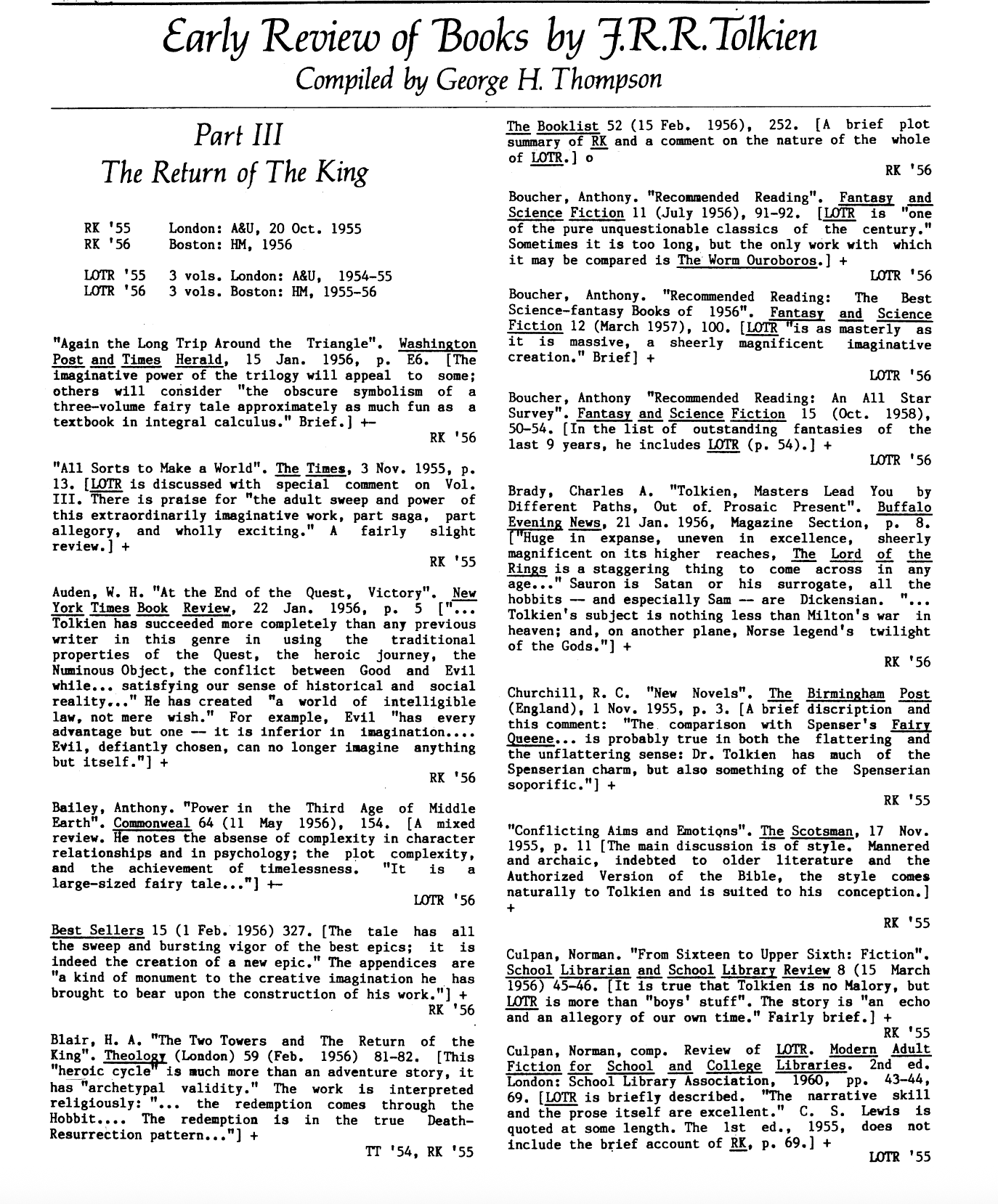

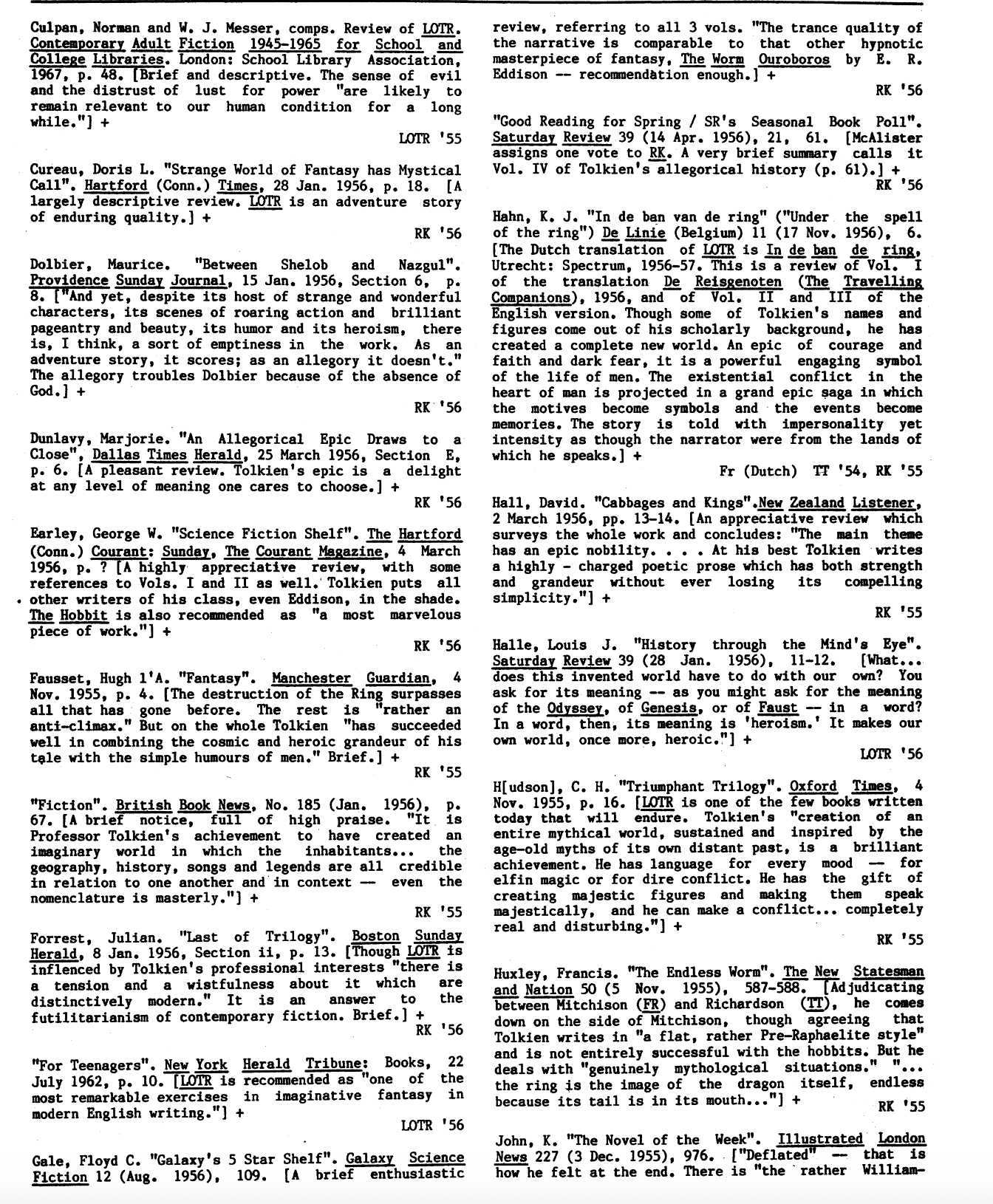

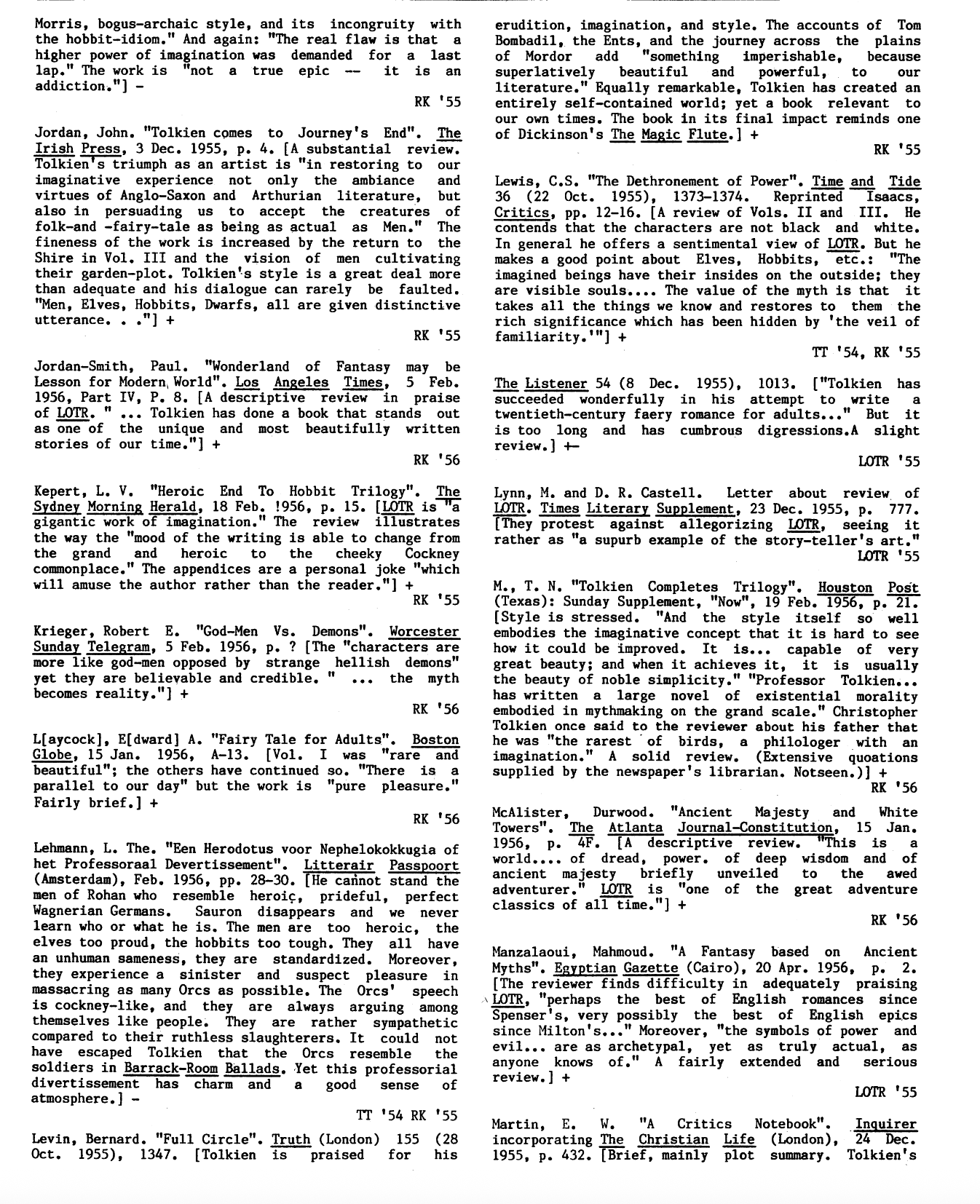

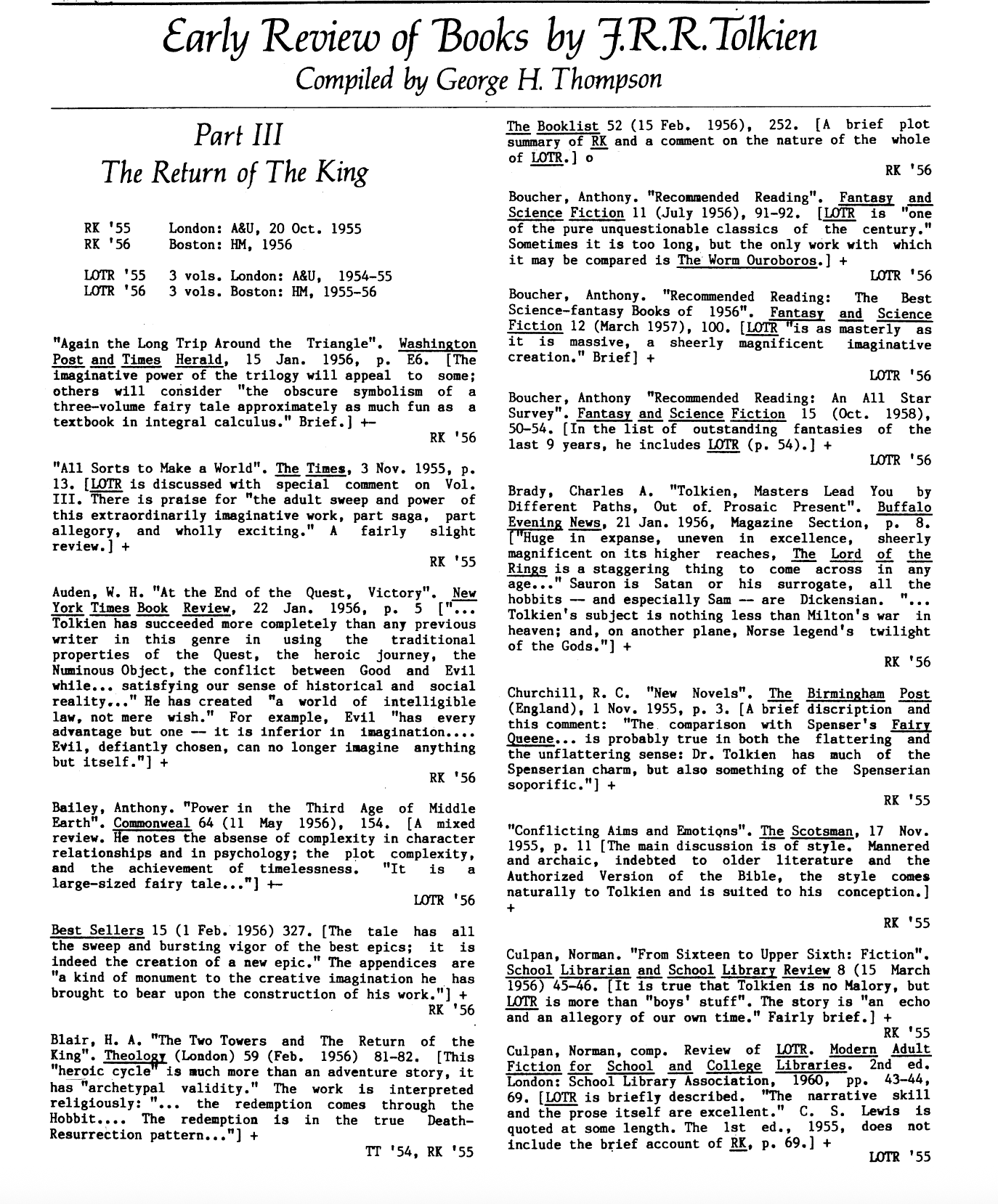

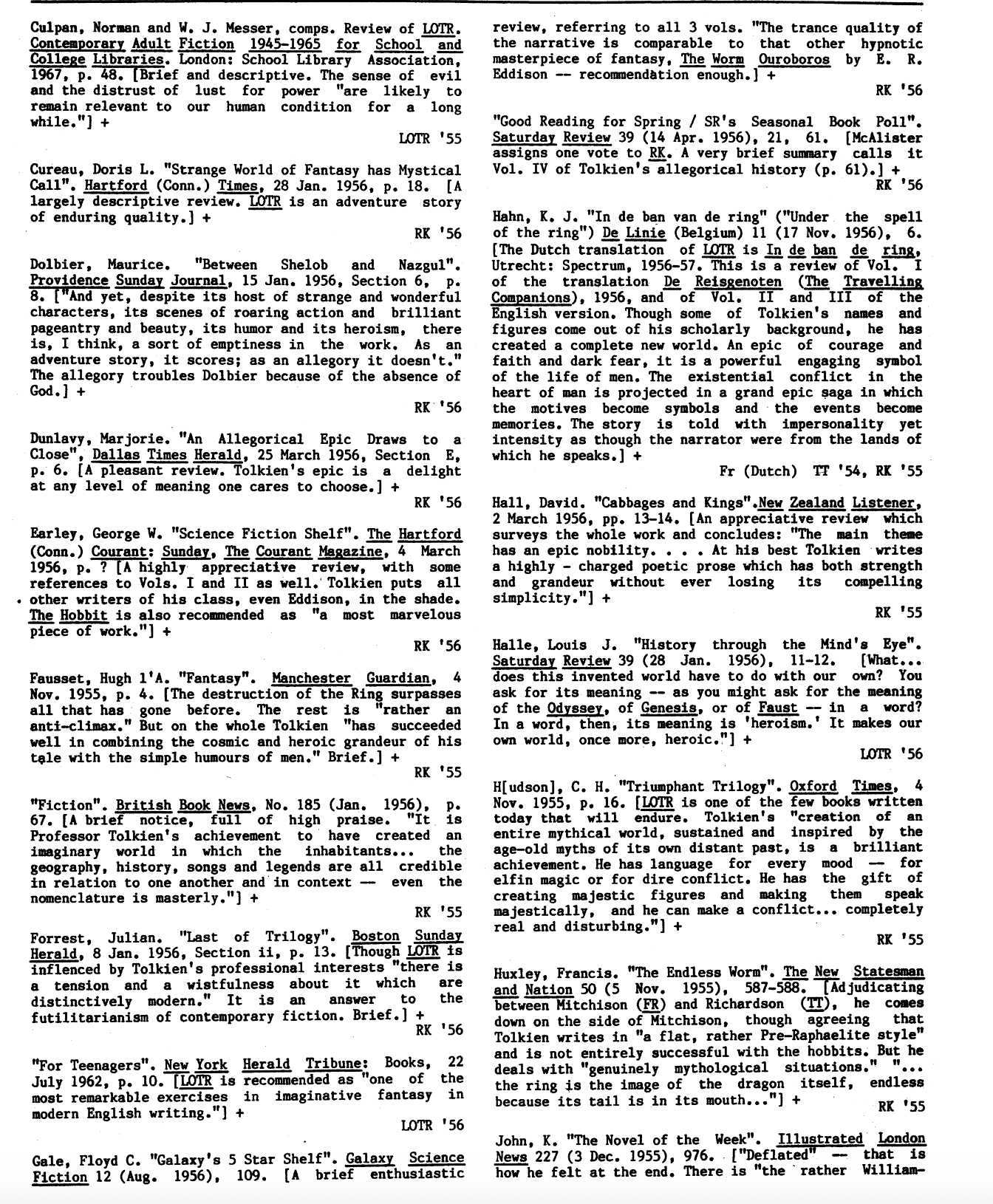

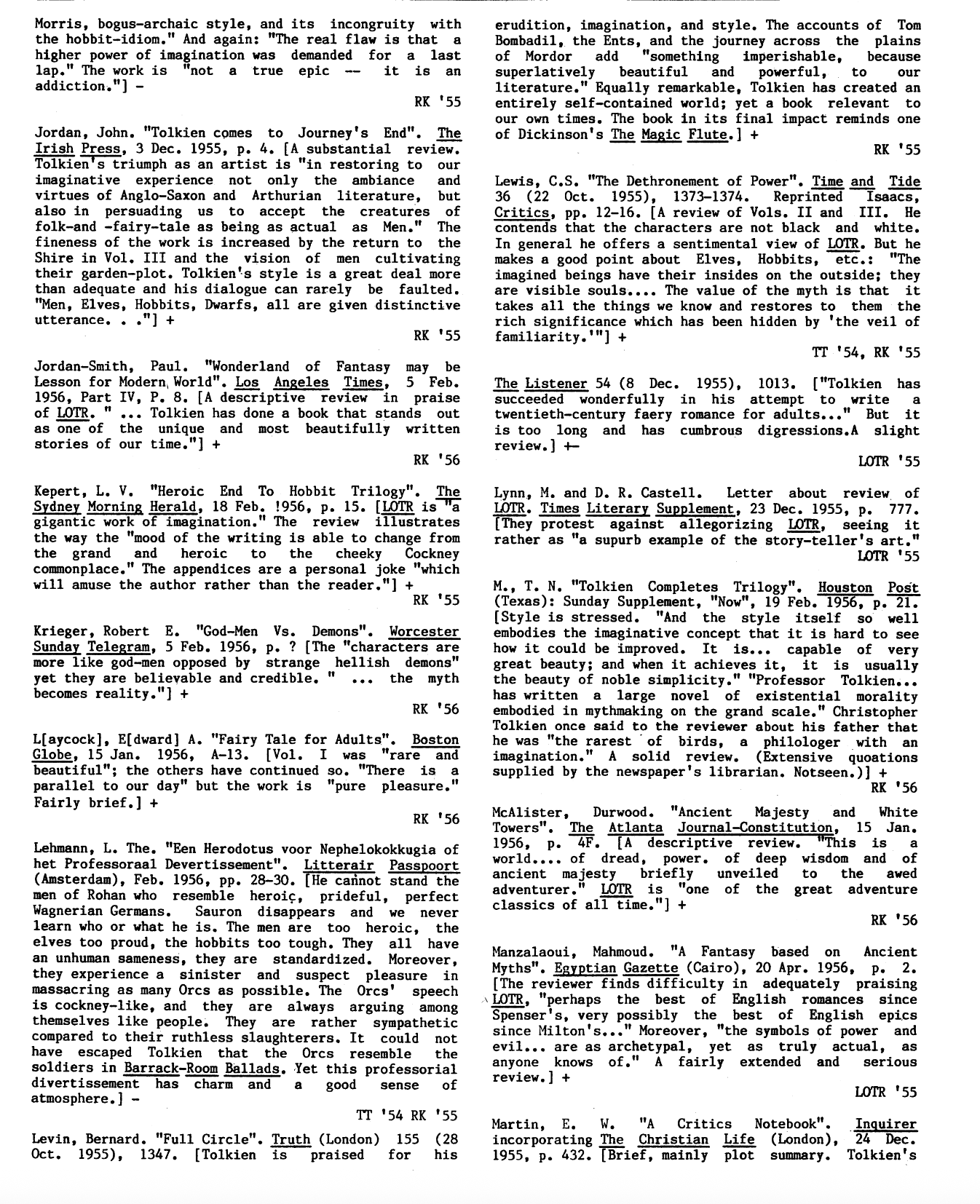

Ever wonder what the Rotten Tomatoes of the day would have looked like for Return of the King in 1955? Here you go:

"It is doubtful...whether the conditions which made such an achievement possible can be reproduced, or whether the work itself can serve as a model for future literary creations. To that extent, its very finality implies an inescapable limitation; but within the limits which this uniqueness imposes, the romance stands in its integrity, a monument to the vigour and consistency which have gone to its making." -Derek Traversi, 1955

Some critique stands the test of time.

It'd be fun to read forum impressions from 1955 of people experiencing it for the first time, but alas that is not possible. However, we can read C.S. Lewis's essay about it two days after its release.

Article: 'When I reviewed the first volume of this work, I hardly dared to hope it would have the success which I was sure it deserved. Happily I am proved wrong. There is, however, one piece of false criticism which had better be answered: the complaint that the characters are all either black or white. Since the climax of Volume I was mainly concerned with the struggle between good and evil in the mind of Boromir, it is not easy to see how anyone could have said this. I will hazard a guess. "How shall a man judge what to do in such times?" asks someone in Volume II. "As he has ever judged," comes the reply. "Good and ill have not changed…nor are they one thing among Elves and Dwarves and another among Men." (II, 40-41).

This is the basis of the whole Tolkinian world. I think some readers, seeing (and disliking) this rigid demarcation of black and white, imagine they have seen a rigid demarcation between black and white people. Looking at the squares, they assume (in defiance of the facts) that all the pieces must be making bishops' moves which confine them to one colour. But even such readers will hardly brazen it out through the last two volumes. Motives, even on the right side, are mixed.

Those who are now traitors usually began with comparatively innocent intentions. Heroic Rohan and imperial Gondor are partly diseased. Even the wretched Smeagol, till quite late in the story, has good impulses; and by a tragic paradox, what finally pushes him over the brink is an unpremeditated speech by the most selfless character of all.

There are two Books in each volume and now that all six are before us the very high architectural quality of the romance is revealed. Book I builds up the main theme. In Book II that theme, enriched with much retrospective material, continues. Then comes the change. In III and V the fate of the company, now divided, becomes entangled with a huge complex of forces which are grouping and regrouping themselves in relation to Mordor. The main theme, isolated from this, occupies IV and the early part of VI (the latter part of course giving all the resolutions). But we are never allowed to forget the intimate connection between it and the rest. On the one hand, the whole world is going to the war; the story rings with galloping hoofs, trumpets, steel on steel. On the other, very far away, two tiny, miserable figures creep (like mice on the slag heap) through the twilight of Mordor. And all the time we know that the fate of the world depends far more on the small movement than on the great. This is a structural invention of the highest order: it adds immensely to the pathos, irony, and grandeur of the tale.

This main theme is not to be treated in those jocular, whimsical tones now generally used by reviewers of "juveniles." It is entirely serious: the growing anguish, the drag of the Ring on the neck, the ineluctable conversion of hobbit into hero in conditions which exclude all hope of fame or fear of infamy. Without the relief offered by the more crowded and bustling Books it would be hardly tolerable.

Yet those Books are not in the least inferior. Of picking out great moments, such as the cock-crow at the Siege of Gondor, there would be no end; I will mention two general, and totally different, excellences. One, surprisingly, is realism. This war has the very quality of the war my generation knew. It is all here: the endless, unintelligible movement, the sinister quiet of the front when "everything is now ready," the flying civilians, the lively vivid friendships, the background of something like despair and the merry foreground, and such heavensent windfalls as a cache of choice tobacco "salvaged" from a ruin. The author has told us elsewhere that his taste for fairy-tale was wakened into maturity by active-service; that, no doubt, is why we can say of his war scenes (quoting Gimli the Dwarf), "There is good rock here. This country has tough bones'" (II, 137). The other excellence is that no individual, and no species, seems to exist only for the plot. All exist in their own right and would have been worth creating for their mere flavour even if they had been irrelevant. Treebeard would have served any other author (if any other could have conceived him) for a whole book.. His eyes are "filled up with ages of memory and long, slow, steady thinking" (II, 66). Through those ages his name has grown with him, so that he cannot now tell it; it would, by now, take too long to pronounce. When he learns that the thing they are standing on is a hill, he complains that this is but "a hasty word" (II, 69) for that which has so much history in it.

How far Treebeard can be regarded as a "portait of the artist" must remain doubtful; but when he hears that some people want to identify the Ring with the hydrogen bomb, and Mordor with Russia, I think he might call it a "hasty" word. How long do people think that a world like his takes to grow? Do they think it can be done as quickly as a modern nation changes its Public Enemy Number One or as modern scientists invent new weapons? When Tolkien began there was probably no nuclear fission and the contemporary incarnation of Mordor was a good deal nearer our shores. But the text itself teaches us that Sauron is eternal; the war of the Ring is only one of a thousand wars against him. Every time we shall be wise to fear his ultimate victory, after which there will be "no more songs." Again and again we shall have good evidence that "the wind is setting East, and the withering of all woods may be drawing near" (II, 76). Every time we win we shall know that our victory is impermanent. If we insist on asking for the moral of the story, that is its moral: a recall from facile optimism and wailing pessimism alike, to that hard, yet not quite desperate, insight into Man's unchanging predicament by which heroic ages have lived. It is here that the Norse affinity is strongest: hammerstrokes, but with compassion.

"But why," some ask, "why, if you have a serious comment to make in the real life of men, must you do it by talking about a phantasmagoric never-never-land of your own?" Because, I take it, one of the main things the author wants to say is that the real life of men is of that mythical and heroic quality. One can see the principle at work in his characterisation. Much that in a realistic work would be done by "character delineation" is here done simply by making the character an elf, a dwarf, or a hobbit. The imagined beings have their insides on the outside; they are visible souls. And Man as a whole, Man pitted against the universe, have we seen him at all till we see that he is like a hero in a fairy-tale? In the book, Eomer rashly contrasts "the green earth" with "legends." Aragorn replies that the green earth itself is "a mighty matter of legend" (II, 37).

The value of the myth is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by "the veil of familiarity." The child enjoys his cold meat, otherwise dull to him, by pretending it is bufalo, just killed with his own bow and arrow. And the child is wise. The real meat comes back to him more savoury for having been dipped in a story; you might say that only then is it real meat. If you are tired of the real landscape, look at it in a mirror. By putting bread, gold, horse, apple, or the very roads into a myth, we do not retreat from reality: we rediscover it. As long as the story lingers in our mind, the real things are more themselves. This book applies the treatment not only to bread or apple but to good and evil, to our endless perils, our anguish and our joys. By dipping them in myth we see them more clearly. I do not think he could have done it any other way.

The book is too original and too opulent for any final judgment on a first reading. But we know at once that it has done things to us. We are not quite the same men. And though we must ration ourselves in our rereadings, I have little doubt that the book will soon take its place among the indispensables.'

C. S. Lewis, "The Dethronement of Power" first published in Time and Tide, 22 October 1955, reprinted in Tolkien and his Critics: Essays on J.R.R. Tolkien and the Lord of the Rings (University of Notre Dame Press, 1968)

Wonderfully stated by Mr. Lewis.

(Tolkien's watercolor sketch of Sauron)

On the other side of the pond, we have W.H. Auden's review for the New York Times. Quite the interesting read, as he describes how LotR was received in high brow, elitist circles at the time, and with some keen insight into good and evil:

Article: January 22, 1956

At the End of the Quest, Victory

By W. H. AUDEN

In "The Return of the King," Frodo Baggins fulfills his Quest, the realm of Sauron is ended forever, the Third Age is over and J. R. R. Tolkien's trilogy "The Lord of the Rings" complete. I rarely remember a book about which I have had such violent arguments. Nobody seems to have a moderate opinion: either, like myself, people find it a masterpiece of its genre or they cannot abide it, and among the hostile there are some, I must confess, for whose literary judgment I have great respect. A few of these may have been put off by the first forty pages of the first chapter of the first volume in which the daily life of the hobbits is described; this is light comedy and light comedy is not Mr. Tolkien's forte. In most cases, however, the objection must go far deeper. I can only suppose that some people object to Heroic Quests and Imaginary Worlds on principle; such, they feel, cannot be anything but light "escapist" reading. That a man like Mr. Tolkien, the English philologist who teaches at Oxford, should lavish such incredible pains upon a genre which is, for them, trifling by definition, is, therefore, very shocking.

The difficulty in presenting a complete picture of reality lies in the gulf between the subjectively real, a man's experience of his own existence, and the objectively real, his experience of the lives of others and the world about him. Life, as I experience it in my own person, is primarily a continuous succession of choices between alternatives, made for a short-term or long-term purpose; the actions I take, that is to say, are less significant to me than the conflicts of motives, temptations, doubts in which they originate. Further, my subjective experience of time is not of a cyclical motion outside myself but of an irreversible history of unique moments which are made by my decisions.

For objectifying this experience, the natural image is that of a journey with a purpose, beset by dangerous hazards and obstacles, some merely difficult, others actively hostile. But when I observe my fellow-men, such an image seems false. I can see, for example, that only the rich and those on vacation can take journeys; most men, most of the time must work in one place.

I cannot observe them making choices, only the actions they take and, if I know someone well, I can usually predict correctly how he will act in a given situation. I observe, all too often, men in conflict with each other, wars and hatreds, but seldom, if ever, a clear-cut issue between Good on the one side and Evil on the other, though I also observe that both sides usually describe it as such. If then, I try to describe what I see as if I were an impersonal camera, I shall produce not a Quest, but a "naturalistic" document.

Both extremes, of course, falsify life. There are medieval Quests which deserve the criticism made by Erich Auerbach in his book "Mimesis":

"The world of knightly proving is a world of adventure. It not only contains a practically uninterrupted series of adventures; more specifically, it contains nothing but the requisites of adventure... Except feats of arms and love, nothing occurs in the courtly world-and even these two are of a special sort: they are not occurrences or emotions which can be absent for a time; they are permanently connected with the person of the perfect knight, they are part of his definition, so that he cannot for one moment be without adventure in arms nor for one moment without amorous entanglement... His exploits are feats of arms, not 'war,' for they are feats accomplished at random which do not fit into any politically purposive pattern."

And there are contemporary "thrillers" in which the identification of hero and villain with contemporary politics is depressingly obvious. On the other hand, there are naturalistic novels in which the characters are the mere puppets of Fate, or rather, of the author who, from some mysterious point of freedom, contemplates the workings of Fate.

If, as I believe, Mr. Tolkien has succeeded more completely than any previous writer in this genre in using the traditional properties of the Quest, the heroic journey, the Numinous Object, the conflict between Good and Evil while at the same time satisfying our sense of historical and social reality, it should be possible to show how he has succeeded. To begin with, no previous writer has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail. By the time the reader has finished the trilogy, including the appendices to this last volume, he knows as much about Tolkien's Middle Earth, its landscape, its fauna and flora, its peoples, their languages, their history, their cultural habits, as, outside his special field, he knows about the actual world.

Mr. Tolkien's world may not be the same as our own: it includes, for example, elves, beings who know good and evil but have not fallen, and, though not physically indestructible, do not suffer natural death. It is afflicted by Sauron, an incarnate of absolute evil, and creatures like Shelob, the monster spider, or the orcs who are corrupt past hope of redemption. But it is a world of intelligible law, not mere wish; the reader's sense of the credible is never violated.

Even the One Ring, the absolute physical and psychological weapon which must corrupt any who dares to use it, is a perfectly plausible hypothesis from which the political duty to destroy it which motivates Frodo's quest logically follows.

To present the conflict between Good and Evil as a war in which the good side is ultimately victorious is a ticklish business. Our historical experience tells us that physical power and, to a large extent, mental power are morally neutral and effectively real: wars are won by the stronger side, just or unjust. At the same time most of us believe that the essence of the Good is love and freedom so that Good cannot impose itself by force without ceasing to be good.

The battles in the Apocalypse and "Paradise Lost," for example, are hard to stomach because of the conjunction of two incompatible notions of Deity, of a God of Love who creates free beings who can reject his love and of a God of absolute Power whom none can withstand. Mr. Tolkien is not as great a writer as Milton, but in this matter he has succeeded where Milton failed. As readers of the preceding volumes will remember, the situation n the War of the Ring is as follows: Chance, or Providence, has put the Ring in the hands of the representatives of Good, Elrond, Gandalf, Aragorn. By using it they could destroy Sauron, the incarnation of evil, but at the cost of becoming his successor. If Sauron recovers the Ring, his victory will be immediate and complete, but even without it his power is greater than any his enemies can bring against him, so that, unless Frodo succeeds in destroying the Ring, Sauron must win.

Evil, that is, has every advantage but one-it is inferior in imagination. Good can imagine the possibility of becoming evil-hence the refusal of Gandalf and Aragorn to use the Ring-but Evil, defiantly chosen, can no longer imagine anything but itself. Sauron cannot imagine any motives except lust for domination and fear so that, when he has learned that his enemies have the Ring, the thought that they might try to destroy it never enters his head, and his eye is kept toward Gondor and away from Mordor and the Mount of Doom.

Further, his worship of power is accompanied, as it must be, by anger and a lust for cruelty: learning of Saruman's attempt to steal the Ring for himself, Sauron is so preoccupied with wrath that for two crucial days he pays no attention to a report of spies on the stairs of Cirith Ungol, and when Pippin is foolish enough to look in the palantir of Orthanc, Sauron could have learned all about the Quest. His wish to capture Pippin and torture the truth from him makes him miss his precious opportunity.

The demands made on the writer's powers in an epic as long as "The Lord of the Rings" are enormous and increase as the tale proceeds-the battles have to get more spectacular, the situations more critical, the adventures more thrilling-but I can only say that Mr. Tolkien has proved equal to them. From the appendices readers will get tantalizing glimpses of the First and Second Ages. The legends of these are, I understand, already written and I hope that, as soon as the publishers have seen "The Lord of the Rings" into a paper-back edition, they will not keep Mr. Tolkien's growing army of fans waiting too long.

Mr. Auden is the author of "Nones" and "The Shield of Achilles" among other volumes of verse.

Ever wonder what the Rotten Tomatoes of the day would have looked like for Return of the King in 1955? Here you go:

"It is doubtful...whether the conditions which made such an achievement possible can be reproduced, or whether the work itself can serve as a model for future literary creations. To that extent, its very finality implies an inescapable limitation; but within the limits which this uniqueness imposes, the romance stands in its integrity, a monument to the vigour and consistency which have gone to its making." -Derek Traversi, 1955

Some critique stands the test of time.

Last edited: