Kdad

Member

Ahead of a new Studio Ghibli film, critics are asking, 'How will we live without Hayao Miyazaki?'

The creative force behind Japanese animation has teased retirement before, but owing to his age and pace of output, we may finally be seeing the final Studio Ghibli film next week.

We are just one week away from the July 14 release of a brand new Studio Ghibli film, supposedly titled "How Do You Live?" — and we know almost nothing about it.

We know it's from the man behind Studio Ghibli, the 82-year-old Hayao Miyazaki, but there has been no trailer or promotional materials. How do we live? In the dark, apparently.

The no-promo strategy is a deliberate one, according to producer Toshio Suzuki. Speaking to Bungei Shunju magazine, he said, "This time we were like, 'Meh, we don't need to do that.'"

We also know Miyazaki came out of retirement for this one. He had made a formal retirement announcement following "The Wind Rises" in 2013 (Studio Ghibli's production department even shut down), and when asked why he came out of retirement this time around, he told the New York Times, "Because I wanted to."

Suzuki even reportedly tried to talk Miyazaki out of a return, but more personal reasons also held sway. Miyazaki said that the new film is meant to act as a farewell letter to his grandson. "How Do You Live?" is reported to be based on a classic 1937 coming-of-age novel of the same name by Genzaburo Yoshino (1899-1981), which follows a 15-year-old Tokyo schoolboy as World War II approaches.

Miyazaki has teased retirement before on multiple occasions (at least two, and possibly four depending on how you count them), and some critics are skeptical that he won't simply be back in another few years.

Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki (right) shakes hands with Studio Ghibli Chairman and Producer Toshio Suzuki during a news conference held to announce his retirement from film in 2013. | REUTERS

Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki (right) shakes hands with Studio Ghibli Chairman and Producer Toshio Suzuki during a news conference held to announce his retirement from film in 2013. | REUTERS"After 'The Wind Rises,' I thought, and so did Toshio Suzuki, that Miyazaki was really going to retire," says Kan Yanagibashi, a freelance writer who has reported on Studio Ghibli and wrote a series of Ghibli storybooks. "But (even) at the time, he hinted at the possibility of working on short films. In fact, he started working on "Boro the Caterpillar" for the Ghibli Museum shortly thereafter. And even if it's a short film, making any film ignites a director's creativity."

Miyazaki's cycle of retirements dates back to 1997's "Princess Mononoke." Yanagibashi says that the way Miyazaki pours his heart and soul into every work leads the director into a cycle of burnout. By the time he finishes the film he's working on, he can't fathom starting on a new one.

However, the director's age and the increasing length of time between his films — five years passing between "Ponyo" (2008) and "The Wind Rises," doubled to 10 in between "The Wind Rises" and this latest film — lead many to believe the writing is on the wall. "Because of his own rigorous demands and the need for physical stamina, it takes a long time to produce a new feature film," critic Reiichi Narima told Real Sound magazine. "So I do believe this will be the final film directed by Miyazaki."

There is no way to understate Miyazaki's importance to Japanese animation as a whole or Studio Ghibli more specifically. When he directs a film, he has complete creative control and authority. He even held great sway over films he wasn't directly involved with, which former Ghibli lead producer Yoshiaki Nishimura says factored into his own decision to found a separate animation studio, Studio Ponoc.

"The work of both Goro Miyazaki and Hiromasa Yonebayashi became 'Ghibli-fied' thanks to Hayao Miyazaki's involvement in the planning and scripting," Yanagibashi says, "aided by Ghibli-esque charming characters and detailed background art."

Goro Miyazaki, son of Hayao Miyazaki, poses in a garden on the roof of Studio Ghibli in 2006. | REUTERS

Goro Miyazaki, son of Hayao Miyazaki, poses in a garden on the roof of Studio Ghibli in 2006. | REUTERSStill, Studio Ghibli's recent films beyond Miyazaki's, as well as those of Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, have proved unsteady as a whole. The studio's previous effort, "Earwig and the Witch" (2020), directed by Miyazaki's son, Goro, by and large stumbled at the box office and in the eyes of critics.

"'Earwig' was very poor overall, though it had good points in the early scenes and I found its titular character interesting and expressive," says Andrew Osmond, a film and animation journalist, and the author of "Spirited Away: BFI Film Classics."

While earlier Yonebayashi and Goro titles like "Arrietty" (2010), "From Up on Poppy Hill" (2011) and "When Marnie Was There" (2014) performed better than "Earwig and the Witch," none have come close to matching what Miyazaki or Takahata have been able to do at the box office, in the reviews or in the hearts of fans.

"I think 'When Marnie Was There' is excellent, but everything about it was so low-key and ambiguous that it struggled to draw viewers," Osmond adds. "I'm certainly not convinced there will be any more iconic Ghibli films after Miyazaki's departure — or indeed, that there'll be any more Ghibli films at all."

The colossal void left that will be left behind by Miyazaki has many desperately searching for a successor. Although Goro Miyazaki has had some success in his directorial career, few would consider him his father's spiritual or legitimate successor. Yonebayashi, who directed "Arrietty" and "When Marnie Was There," has since joined Nishimura at Studio Ponoc. While it's true he was one of the rare few to receive praise from Hayao Miyazaki himself, Studio Ponoc's films, while solid, have thus far not been able to truly impress.

Filmmaker Mamoru Hosada is considered a promising heir to the animation throne, but his outings "Mirai" (2018) and "Belle" (2021) were perceived by critics and audiences as good, not great.

Outside of the Ghibli-sphere, the romantic worlds of Makoto Shinkai's "Your Name." (2016) and "Suzume" (2022) have spun box-office gold, however they still feel morally and aesthetically simplistic compared to Studio Ghibli at its best.

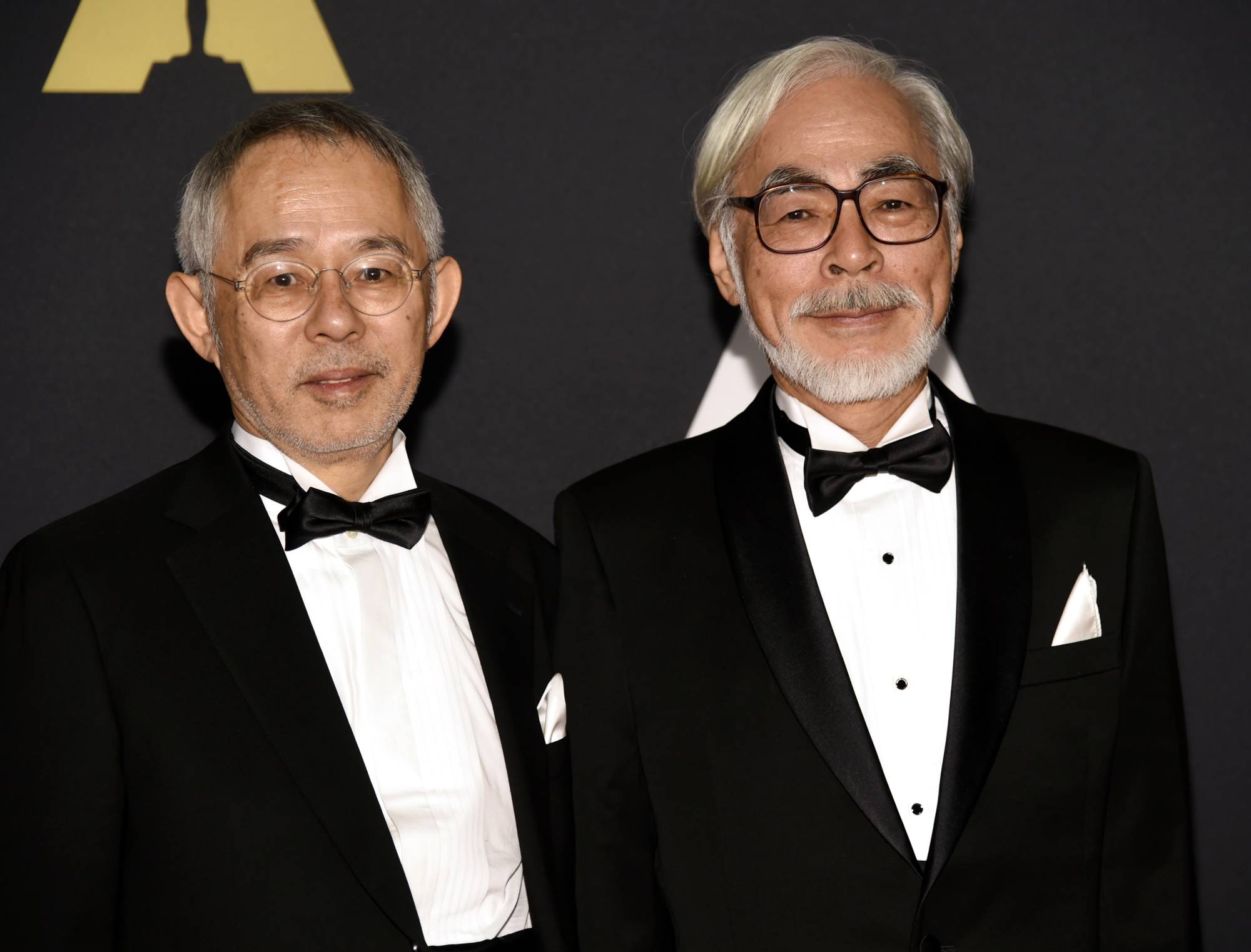

Film producer Toshio Suzuki (left), a long-time colleague of Hayao Miyazaki (right), poses with the animator at an awards ceremony in Los Angeles in 2014. | REUTERS

Film producer Toshio Suzuki (left), a long-time colleague of Hayao Miyazaki (right), poses with the animator at an awards ceremony in Los Angeles in 2014. | REUTERSReal Sound's Narima looks to Hideaki Anno, creator of the "Evangelion" franchise, to carry on the Miyazaki mantle with a potential continuation of "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind." That 1984 feature film covered only the first one-and-a-half volumes of a seven-volume manga series by Miyazaki. "According to Toshio Suzuki, Hayao Miyazaki gave his permission," Narima says, "saying, 'It's fine if Anno is the one to do it.'"

"For Ghibli to move forward, the company must allow new artists to express themselves, and that involves taking risks," Osmond says. "Unfortunately, Ghibli's reputation is that of a studio that would only allow risky ideas that came from Miyazaki, Takahata or Suzuki.

"Unless there's a substantial change in thinking at Ghibli after Miyazaki's departure, I'm doubtful that it can evolve, let alone turn out successful films."

As Suzuki told the New York Times, "The whole purpose of Studio Ghibli is to make Miyazaki films." With the newly established Ghibli Park in Aichi Prefecture giving life to the world of the director's creations in a characteristically refined and nuanced manner, the studio has at least guaranteed itself income and life moving forward, even without any additional titles. How do we live? Maybe off decades of copyright and merchandising.

In the end, Miyazaki's successor might be Japanese animation itself. His influence has disseminated throughout the industry and helped push it forward. Eddie Moriya, chief business development officer for Polygon Pictures' digital animation house, told Variety recently, "Each studio's effort to try new ways of expression, while referring to Ghibli and other great works, is what brings progress and advancement to the anime industry."

Excitement is high ahead of the release of "How Do You Live?," with the lack of promotion only raising expectations higher. Talk of a successor can come later, at this point the only act that has to follow Miyazaki's impressive body of work is Miyazaki himself.