Bayonetta draws upon a wide variety of sources of inspiration for its visuals, story, and action, but none are as distinct or complicated as the game's relationship to Art Nouveau, the misunderstood flash in the pan of the fin de siècle. I highly suggest taking the time to read through this whole post before commenting, as I will likely be answering many of your questions. This post is more or less a rough summary of a paper I wanted to do for a seminar on Art Nouveau, but as you will see eventually, I was unable to develop a rock-solid thesis and had to abandon the project in order to study the influence of Alphonse Mucha on fanart posted to DeviantArt. (Yes, I'll post some of those later in this thread) This thread will be pretty much limited to the first Bayonetta, mostly due to my own lack of time. So, without further ado,

What is Art Nouveau? There genuinely is no good answer, largely because Art Nouveau, unlike say Cubism or Abstract Expressionism, is not defined by an ideology but by an admiration of beauty and the natural world that was expressed in a wide variety of ways. Separate schools developed in Paris, Brussels, Glasgow, Turin, Chicago, Vienna, Barcelona, etc. each with their own ideas and style. It grew quickly from nothing in the late 1890s and by 1905 had effectively died, only to be revived in the 1960s. Bayonetta draws primarily from the artists and events in Paris, so it will be the biggest focus.

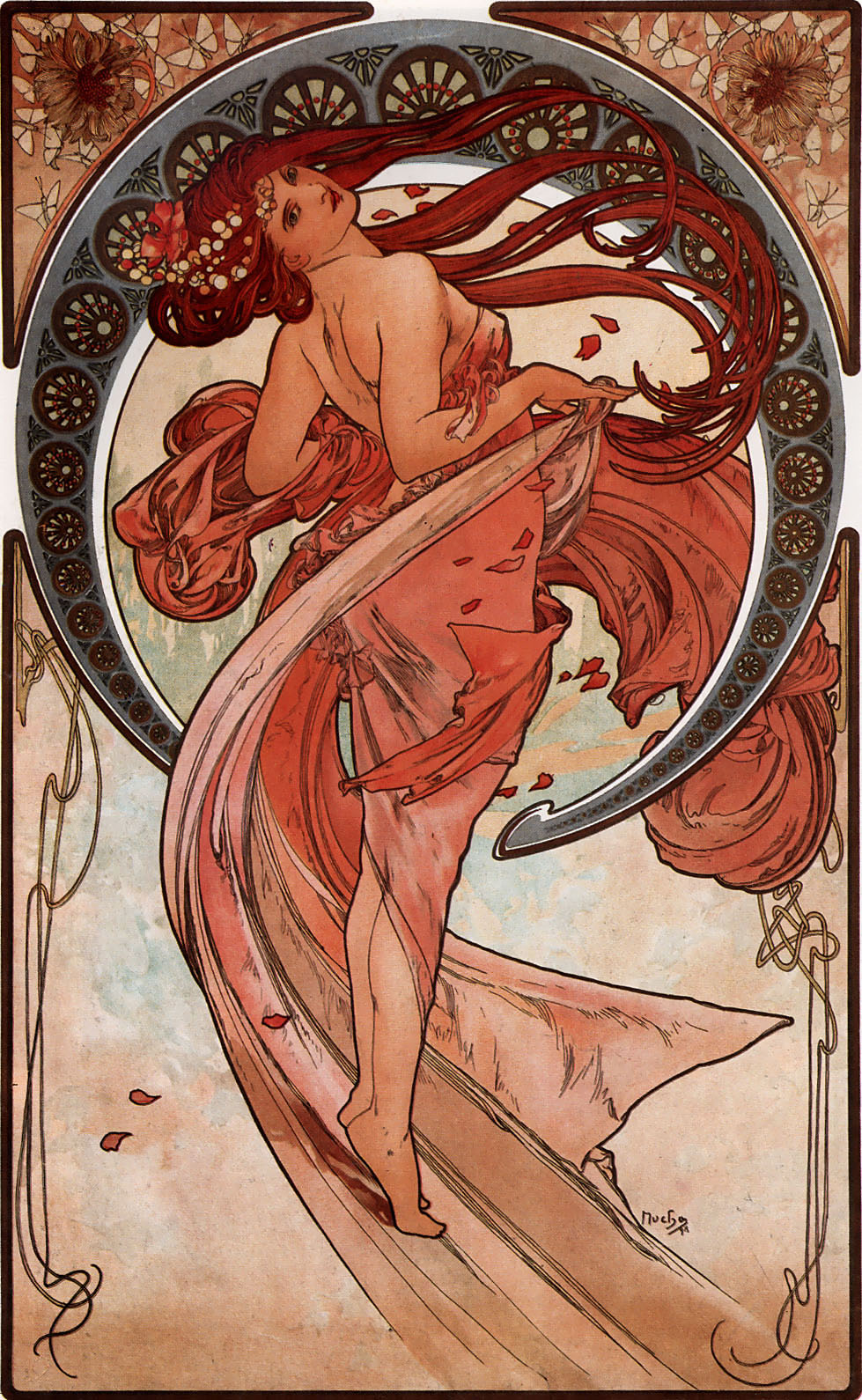

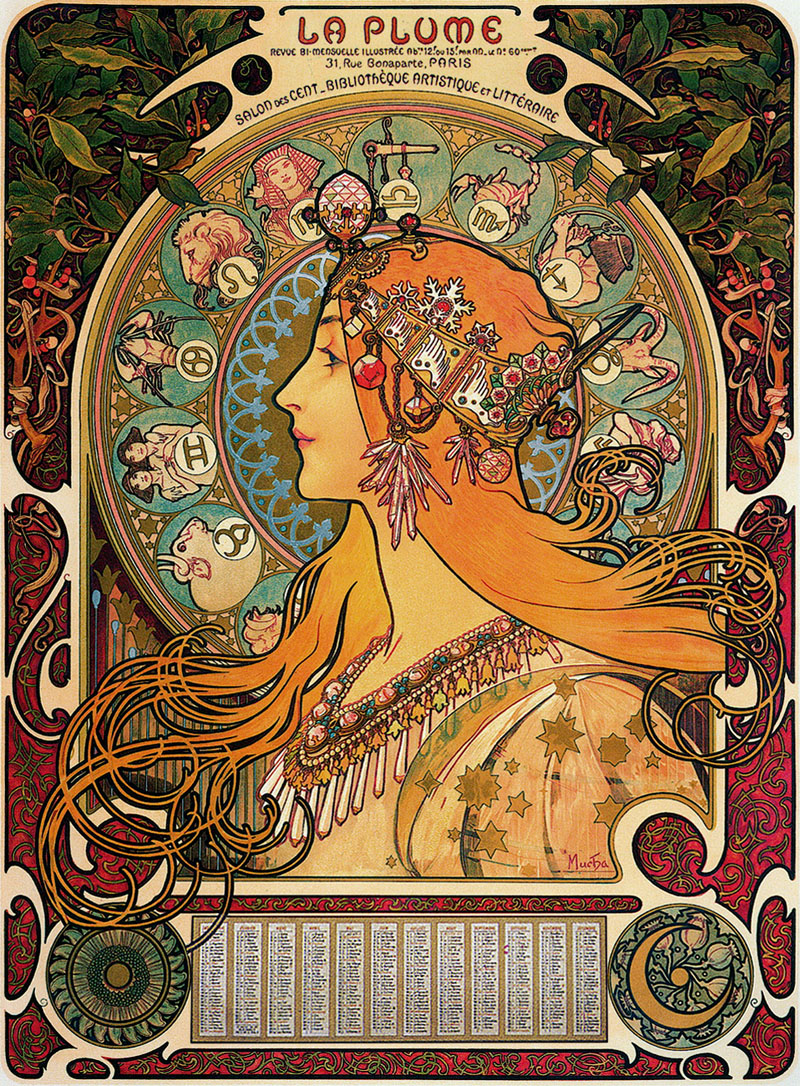

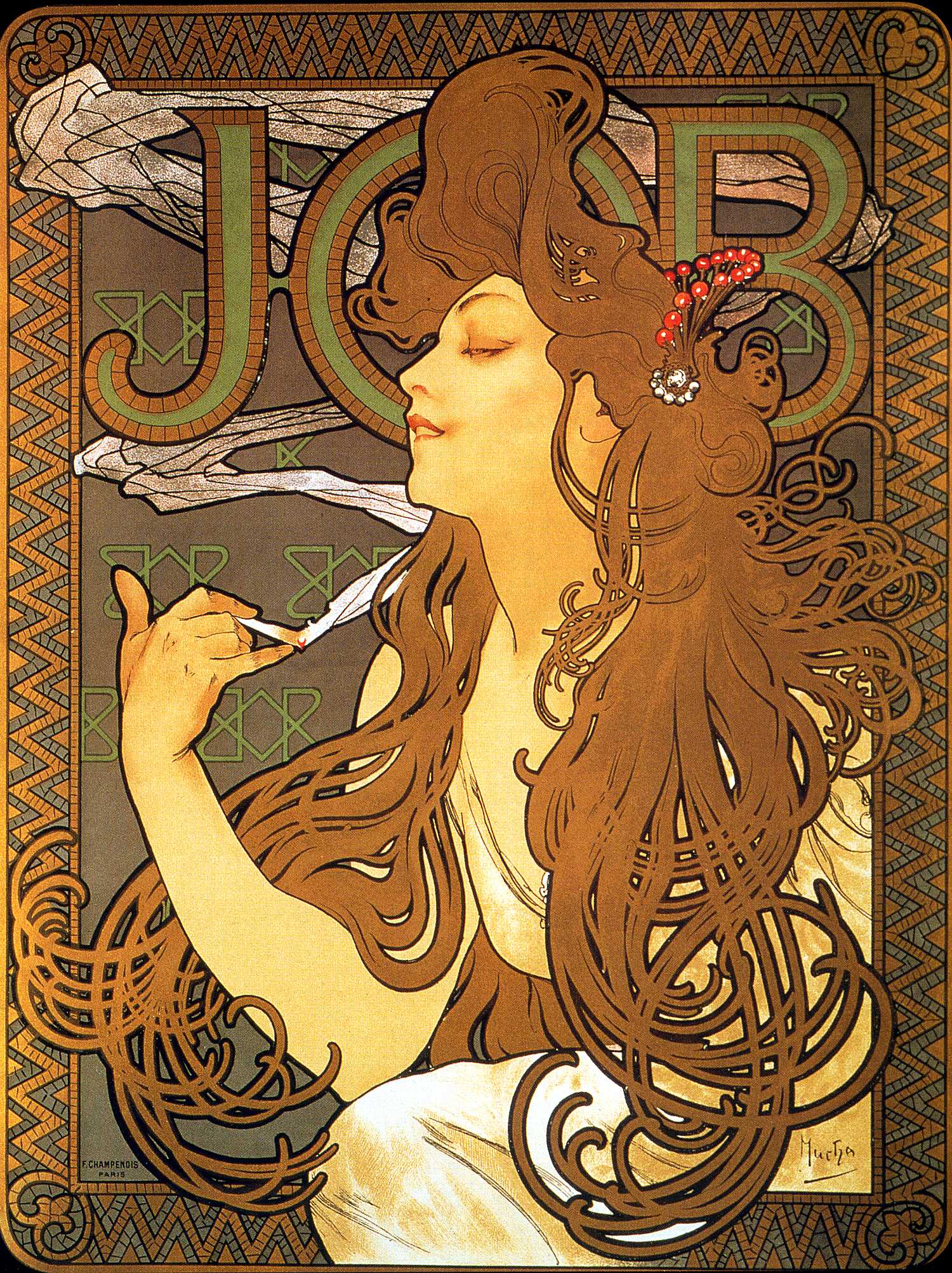

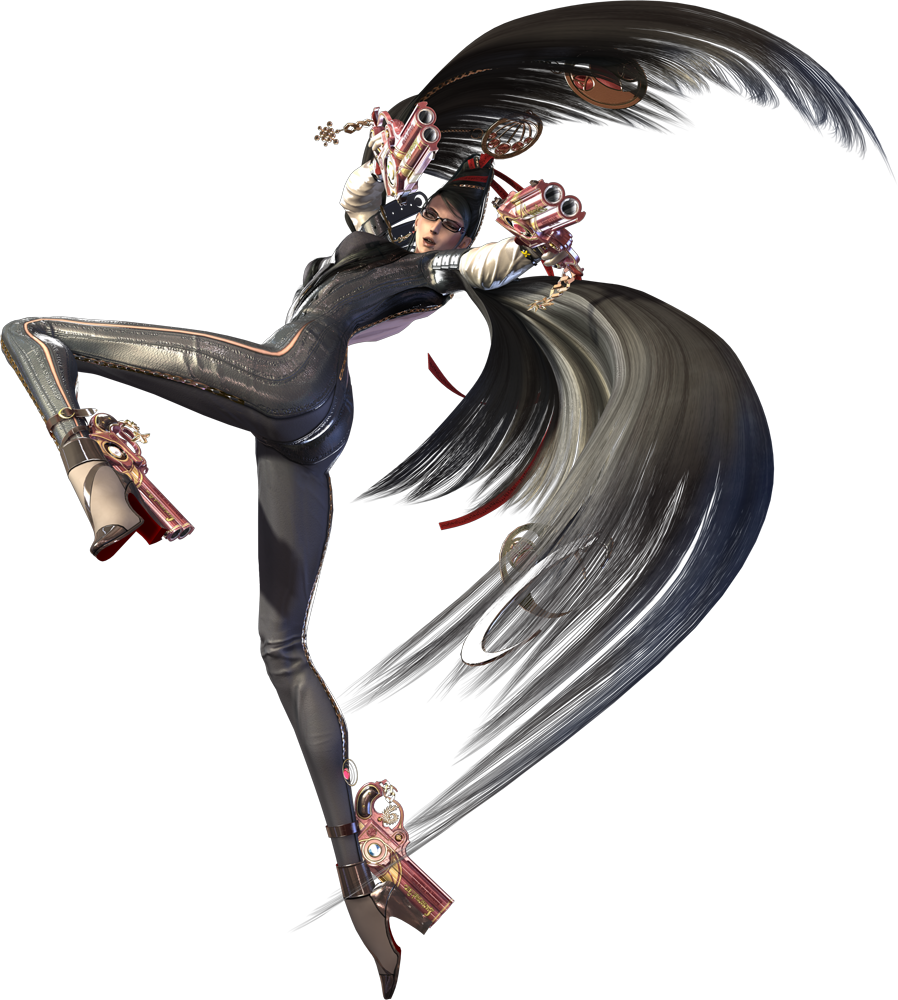

Magical hair is also a consistent theme in Art Nouveau prints, especially Alphonse Mucha's advertising masterpieces. Unlike Bayonetta's hair though, the hair he depicts is flighty, weightless where Bayonetta's weaves are heavy and powerful, exerting gigatons of force. Mucha's hair is beautiful, but weak while Bayonetta's manages to be both attractive and strong. Also note the circular emplems which are quite similar to the Umbran portals through which Bayonetta sends out her Wicked Weaves.

However, and this is where I began to run into trouble in my research paper, I am going to make the argument that the comparisons between Bayonetta and Art Nouveau go much, much deeper than just art design aesthetics. I argue that the gameplay, story, and Bayonetta's complex depiction as a character are all indebted to Art Nouveau ideas and historic events. I argue this due to my own interpretation of the game, as the primary sources for this read are thin, at best, and not indicative of much influence. In the few interviews translated into English, the art design of Bayonetta 1 is referred to as old-style or traditional while Bayonetta 2 is modern. There are no specific references to Art Nouveau in these primary sources, so most of this hot take is developed from my experience with the game and my knowledge of Art Nouveau. Hopefully I'll show you how to look at Bayonetta in a new light. I'll be making my case by looking at an Art Nouveau dancer Loie Fuller, the popular story of Salome, and will look into the ways gender evolved and was understood at the turn of the century through Art Nouveau, in ways both positive, encouraging the development of the "New Woman",and, at times, blatantly misogynistic.

So, Loie Fuller is the first of the 2 female performers who took Paris by storm. Loie Fuller captured the imaginations of Parisians through her unique form of dance, which involved wearing a gigantic, and extremely heavy, outfit like a sail cloth and spinning and shaking at great speeds alongside lights and music. Just take a look at this wonderfully weird performance Look familiar? Loie Fuller's performances were full-on spectacles that used light, music, and Loie's strange choreography to create an otherworldly experience whose flowing forms are evocative of the way Bayonetta's hair turns into weapons. (The comparison is probably more clear here with these posters which look nothing like Loie herself, there's a story from her autobiography about a young girl wandering backstage and seeing Loie, who was by no means sprightly as she needed serious muscle to hoist her costumes, and saying "You're not Loie, the Loie I saw was a fairy!")

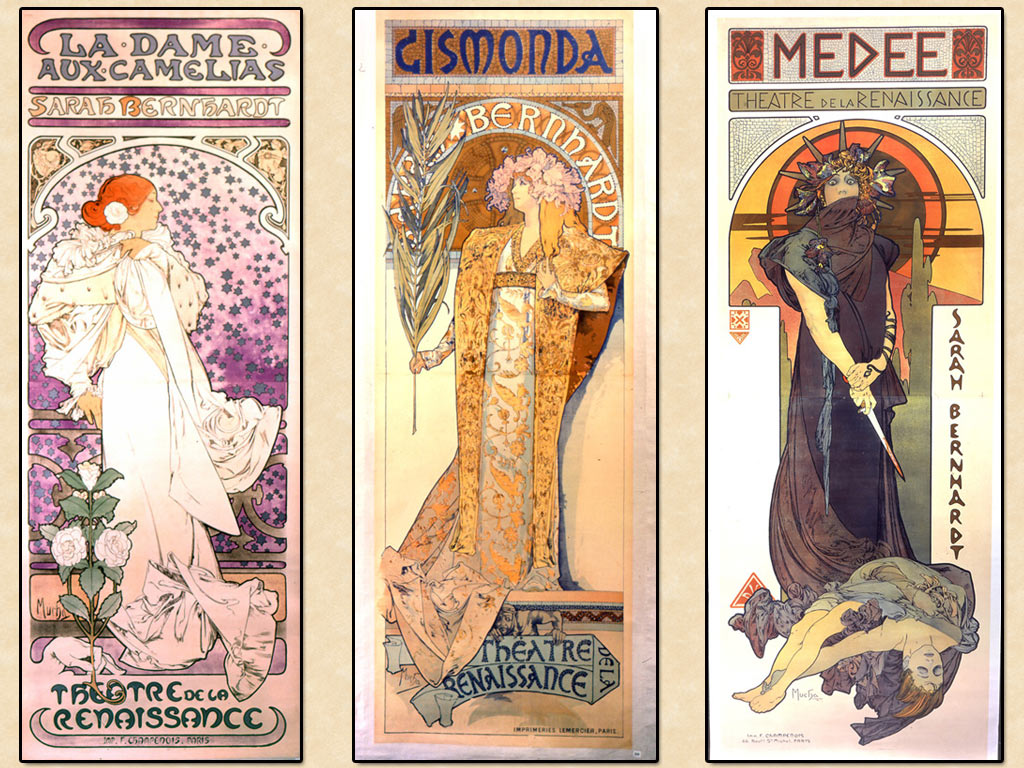

The story of Salomé is another link between Bayonetta and Art Nouveau, providing an example of a femme-fatale who used her seductive powers for her own means. Salomé became significant in the 1890s due to Oscar Wilde's play, which was banned from being performed in England due to its Biblical content, so Wilde translated it into French and, unsuccessfully tried to get Sarah Bernhardt, the other Art Nouveau superstar performer, to play the titular character. Something about Wilde's Salomé was so fascinating and strikingly bold that it triggered a state of "Salomania" in Paris and led to many copy-cat performances. The story is more than a little similar to Bayonetta's, as Salomé uses her beauty to seduce and ultimately betray her step-father by killing John the Baptist, who in this version of the story had failed to respond to Salomé's advances. (Yes it lacks the weird time-travel paradoxes and has a love interest unlike Bayonetta, but the core principal of the femme fatale using her power, expressed through some attribute of physical beauty, to betray a father figure is present). It also raises questions about what to what degree a female character in an artwork can express agency through their actions while simultaneously being "onstage" performing for an audience in ways otherwise would look exploitative. Is Salomé's dance for King Herod is both the ultimate expression of power for her character and a tantalizing peep-show for a cosmopolitan audience accustomed to much more subdued sexual content in their entertainment. Sound familiar? (Below I've included a couple of Sarah Bernhardt's posters to demonstrate how her stardom was not built upon the kind of raunchy appeal to drama that is such a central component of Wilde's Salomé and the most famous image from Aubrey Beardsley's 16 piece series made to accompany Wilde's Salomé, which took a different, but no less effective approach to creating an empowered female character. The poster for Richard Strauss' opera version of Salomé is also remarkable given that it was made in 1910 after Art Nouveau had passed out of style.)

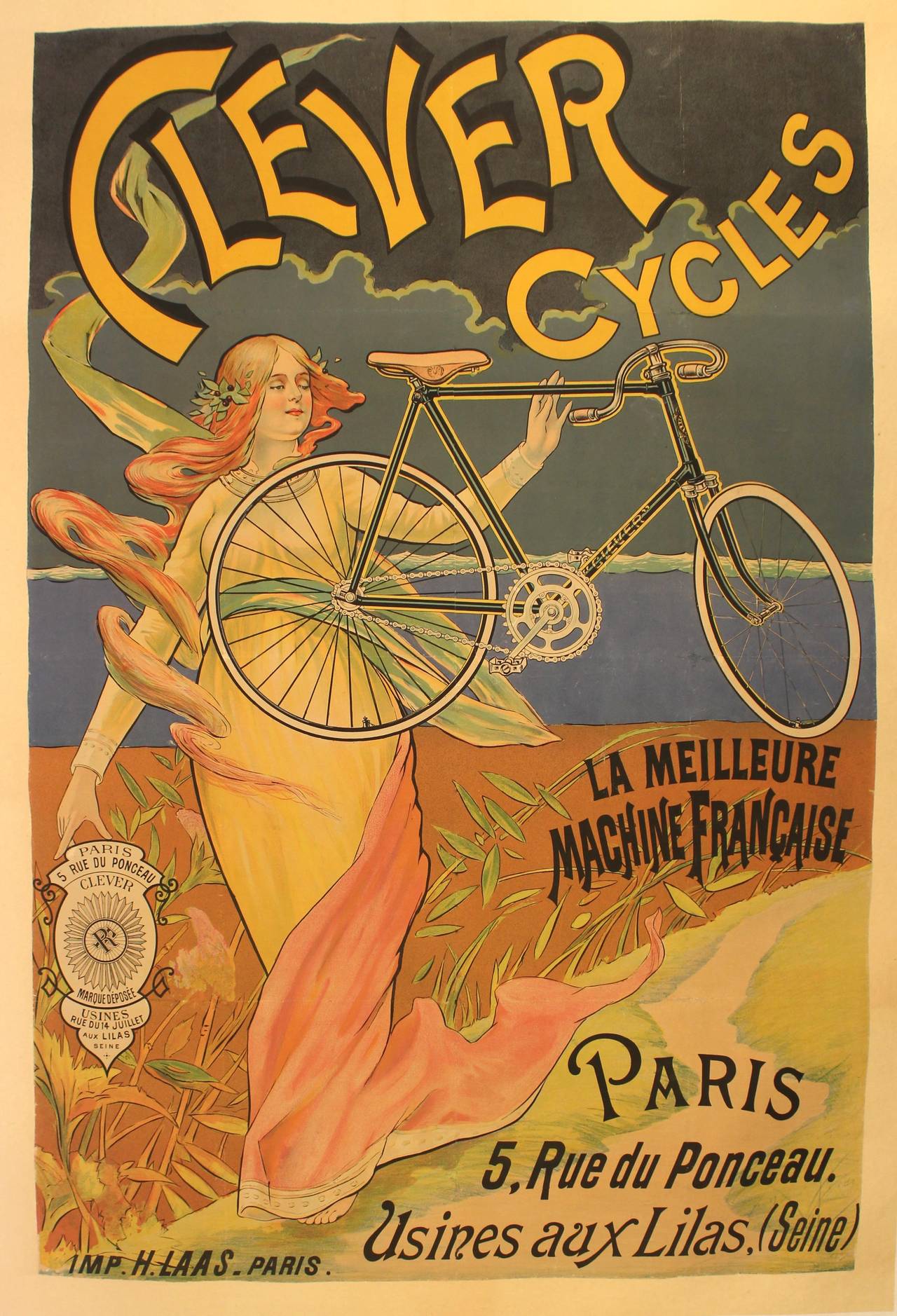

Art Nouveau both deified women and objectified them, which makes it challenging to say whether it had a positive effect on their lives. To understand this we have to remember what Paris at the turn of the century was like and how new developments in technology and changes in societal structure were allowing women to get out of the home and gain independence. Electricity first began to reduce the burdens of everyday life during this period and as Paris grew larger under Haussman's urban design women had to, out of necessity, leave the home, which due to the bicycle, they could now do with relative ease. No longer did an upper class woman have to wait for a male chaperone wit horse and carriage to take them to their destination, they could simply hop on a bicycle and get there themselves. This was a huge controversy in Paris at the time and saw fierce debate, but it quickly became normal and businesses quickly responded to the new influx of female customers by designing department stores that would most appeal to them. The bicycle was both a tool of liberation and a sign of a society heading down the wrong path. (Note that there are tons more posters with naked ladies holding bikes and I'm not really sure how to read them, some seem empowering while others are awful examples of male gaze. The photo of Bayonetta and Jeanne from Bayo 2 is so evocative of department store culture that I couldn't resist throwing it in too, even though it's closer to Art Deco glamour of the 1920s, it's still a nice shout-out to the new level of freedom made possible by consumer spending.)

Much of Art Nouveau actually came to represent those who saw female liberation as a mistake, as part of the market shifted towards bitter old men. Art Nouveau jewelry explicitly turned female forms into wearable tokens that reduced them to mere objects, often melding female forms with plants into strange chimeras. And lets not get started on Rupert Carabin's carved wood furniture, seriously, it's all tastelessly misogynistic(and very NSFW). What makes Bayonetta powerful is not just her hair, but her choice to exercise her free will and go out and kick some Angel ass, the same type of moral freedom that many at the turn of the century worried would throw society into chaos. By fetishizing the female form, without actually respecting the women who actually emobided those forms, Art Nouveau artists and patrons looked to control them and prevent them from acting out. So much like Bayonetta, there are valid concerns that Art Nouveau also objectifies women through use of the othering and the male gaze, but whether those elements outweigh the positive, empowering depictions is up to the viewer.

So, in summary, the art team at Platinum drew upon the alluring stylistic elements of Art Nouveau to help make the game look like nothing else on the market, but the relationship with the art style is also closely related to the story and specific historic trends that were occurring in tandem with Art Nouveau. What are your thoughts, did Bayonetta's art style draw you in or repel you? Is your Japanese better than mine and can you tell if the designers were actually talking about Art Nouveau?

Thanks for reading this far, hope you enjoyed the pretty pictures. If you enjoyed this thread then I'd suggest you check out my last thread on how Breath of the Wild draws upon 19th century painting for its style and scenery.

What is Art Nouveau? There genuinely is no good answer, largely because Art Nouveau, unlike say Cubism or Abstract Expressionism, is not defined by an ideology but by an admiration of beauty and the natural world that was expressed in a wide variety of ways. Separate schools developed in Paris, Brussels, Glasgow, Turin, Chicago, Vienna, Barcelona, etc. each with their own ideas and style. It grew quickly from nothing in the late 1890s and by 1905 had effectively died, only to be revived in the 1960s. Bayonetta draws primarily from the artists and events in Paris, so it will be the biggest focus.

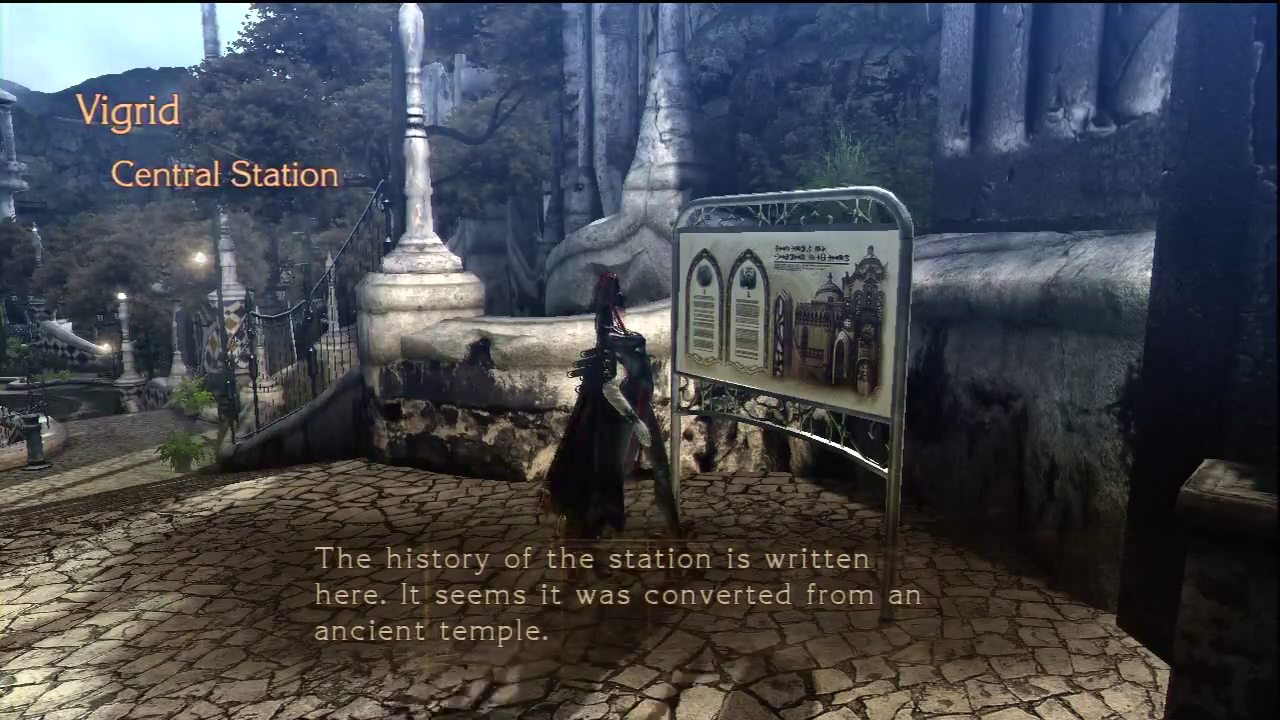

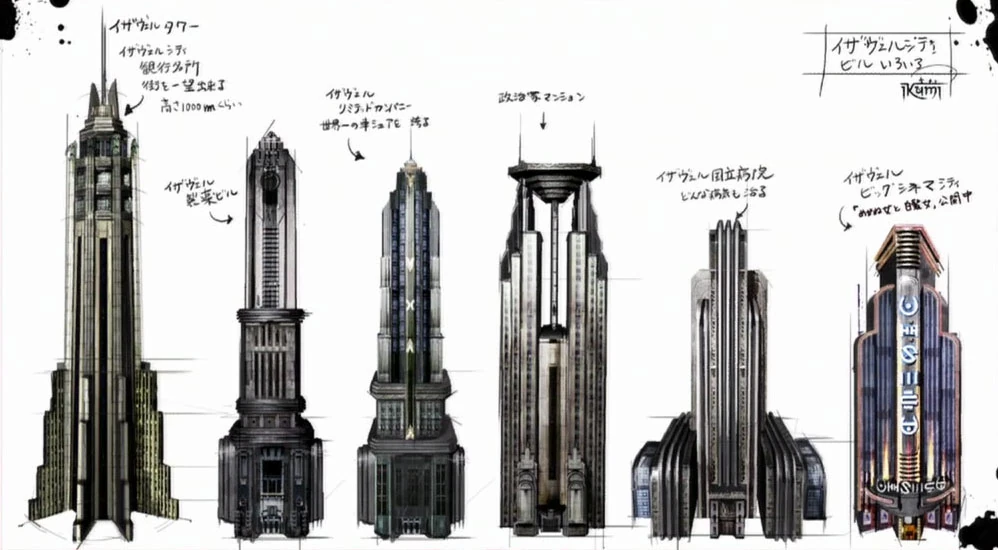

The clearest, and least disputable of Bayonetta's sources from Art Nouveau can be seen in the strange architecture of Vigrid. Much of Vigrid's large buildings bear clear influence to Antoni Gaudi, the architect from Barcelona whose works with the Güell family and plans for the Sagrada Familia incorporated strange organic, yet amorphous forms covered in glittering mosaic tiles. Hector Guimard's famous entrances to the Paris Metro also influence the design of the message boards within Vigrid that provide a little backstory to the city.

The train station the game begins in is another place where the influence can be clearly seen, as a mesh of Louis Comfort Tiffany's stained glass and Guimard's ornate cast-iron railings. Other places such as Rodin's bar, the Gates of Hell, also look as if they could be plucked from an alternate universe Art Nouveau that embraced Gothic sensibilities as well.

Magical hair is also a consistent theme in Art Nouveau prints, especially Alphonse Mucha's advertising masterpieces. Unlike Bayonetta's hair though, the hair he depicts is flighty, weightless where Bayonetta's weaves are heavy and powerful, exerting gigatons of force. Mucha's hair is beautiful, but weak while Bayonetta's manages to be both attractive and strong. Also note the circular emplems which are quite similar to the Umbran portals through which Bayonetta sends out her Wicked Weaves.

However, and this is where I began to run into trouble in my research paper, I am going to make the argument that the comparisons between Bayonetta and Art Nouveau go much, much deeper than just art design aesthetics. I argue that the gameplay, story, and Bayonetta's complex depiction as a character are all indebted to Art Nouveau ideas and historic events. I argue this due to my own interpretation of the game, as the primary sources for this read are thin, at best, and not indicative of much influence. In the few interviews translated into English, the art design of Bayonetta 1 is referred to as old-style or traditional while Bayonetta 2 is modern. There are no specific references to Art Nouveau in these primary sources, so most of this hot take is developed from my experience with the game and my knowledge of Art Nouveau. Hopefully I'll show you how to look at Bayonetta in a new light. I'll be making my case by looking at an Art Nouveau dancer Loie Fuller, the popular story of Salome, and will look into the ways gender evolved and was understood at the turn of the century through Art Nouveau, in ways both positive, encouraging the development of the "New Woman",and, at times, blatantly misogynistic.

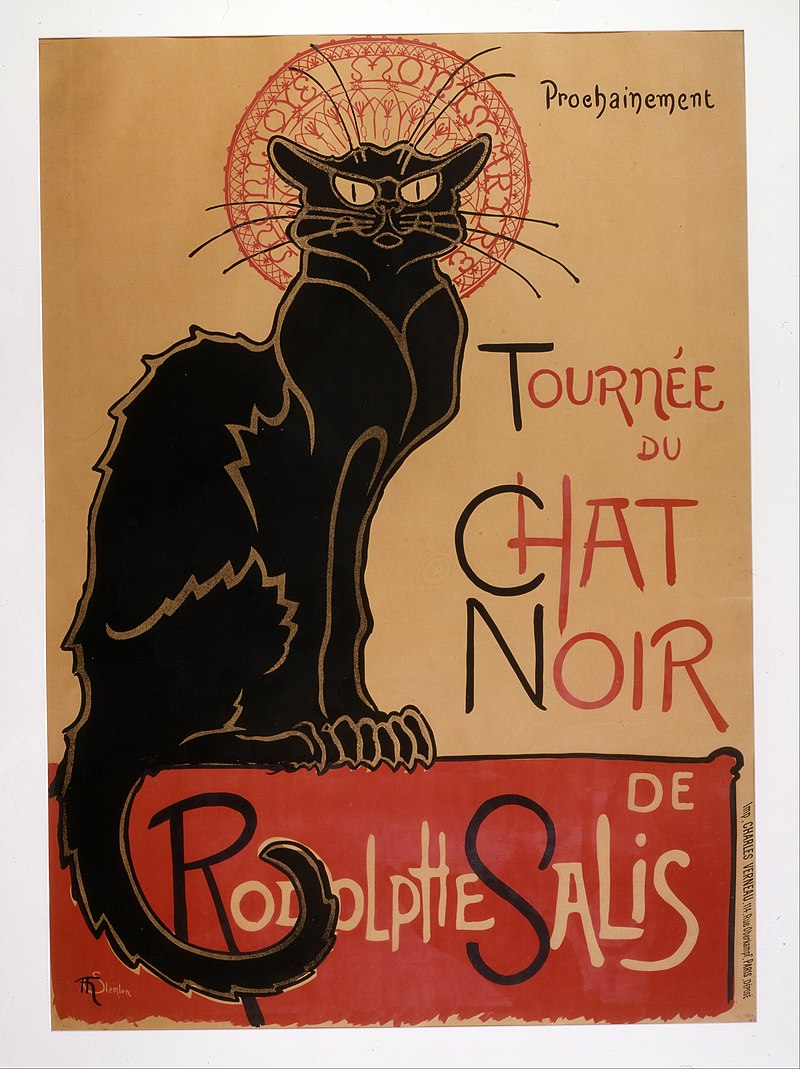

So, Loie Fuller is the first of the 2 female performers who took Paris by storm. Loie Fuller captured the imaginations of Parisians through her unique form of dance, which involved wearing a gigantic, and extremely heavy, outfit like a sail cloth and spinning and shaking at great speeds alongside lights and music. Just take a look at this wonderfully weird performance Look familiar? Loie Fuller's performances were full-on spectacles that used light, music, and Loie's strange choreography to create an otherworldly experience whose flowing forms are evocative of the way Bayonetta's hair turns into weapons. (The comparison is probably more clear here with these posters which look nothing like Loie herself, there's a story from her autobiography about a young girl wandering backstage and seeing Loie, who was by no means sprightly as she needed serious muscle to hoist her costumes, and saying "You're not Loie, the Loie I saw was a fairy!")

The story of Salomé is another link between Bayonetta and Art Nouveau, providing an example of a femme-fatale who used her seductive powers for her own means. Salomé became significant in the 1890s due to Oscar Wilde's play, which was banned from being performed in England due to its Biblical content, so Wilde translated it into French and, unsuccessfully tried to get Sarah Bernhardt, the other Art Nouveau superstar performer, to play the titular character. Something about Wilde's Salomé was so fascinating and strikingly bold that it triggered a state of "Salomania" in Paris and led to many copy-cat performances. The story is more than a little similar to Bayonetta's, as Salomé uses her beauty to seduce and ultimately betray her step-father by killing John the Baptist, who in this version of the story had failed to respond to Salomé's advances. (Yes it lacks the weird time-travel paradoxes and has a love interest unlike Bayonetta, but the core principal of the femme fatale using her power, expressed through some attribute of physical beauty, to betray a father figure is present). It also raises questions about what to what degree a female character in an artwork can express agency through their actions while simultaneously being "onstage" performing for an audience in ways otherwise would look exploitative. Is Salomé's dance for King Herod is both the ultimate expression of power for her character and a tantalizing peep-show for a cosmopolitan audience accustomed to much more subdued sexual content in their entertainment. Sound familiar? (Below I've included a couple of Sarah Bernhardt's posters to demonstrate how her stardom was not built upon the kind of raunchy appeal to drama that is such a central component of Wilde's Salomé and the most famous image from Aubrey Beardsley's 16 piece series made to accompany Wilde's Salomé, which took a different, but no less effective approach to creating an empowered female character. The poster for Richard Strauss' opera version of Salomé is also remarkable given that it was made in 1910 after Art Nouveau had passed out of style.)

Art Nouveau both deified women and objectified them, which makes it challenging to say whether it had a positive effect on their lives. To understand this we have to remember what Paris at the turn of the century was like and how new developments in technology and changes in societal structure were allowing women to get out of the home and gain independence. Electricity first began to reduce the burdens of everyday life during this period and as Paris grew larger under Haussman's urban design women had to, out of necessity, leave the home, which due to the bicycle, they could now do with relative ease. No longer did an upper class woman have to wait for a male chaperone wit horse and carriage to take them to their destination, they could simply hop on a bicycle and get there themselves. This was a huge controversy in Paris at the time and saw fierce debate, but it quickly became normal and businesses quickly responded to the new influx of female customers by designing department stores that would most appeal to them. The bicycle was both a tool of liberation and a sign of a society heading down the wrong path. (Note that there are tons more posters with naked ladies holding bikes and I'm not really sure how to read them, some seem empowering while others are awful examples of male gaze. The photo of Bayonetta and Jeanne from Bayo 2 is so evocative of department store culture that I couldn't resist throwing it in too, even though it's closer to Art Deco glamour of the 1920s, it's still a nice shout-out to the new level of freedom made possible by consumer spending.)

Much of Art Nouveau actually came to represent those who saw female liberation as a mistake, as part of the market shifted towards bitter old men. Art Nouveau jewelry explicitly turned female forms into wearable tokens that reduced them to mere objects, often melding female forms with plants into strange chimeras. And lets not get started on Rupert Carabin's carved wood furniture, seriously, it's all tastelessly misogynistic(and very NSFW). What makes Bayonetta powerful is not just her hair, but her choice to exercise her free will and go out and kick some Angel ass, the same type of moral freedom that many at the turn of the century worried would throw society into chaos. By fetishizing the female form, without actually respecting the women who actually emobided those forms, Art Nouveau artists and patrons looked to control them and prevent them from acting out. So much like Bayonetta, there are valid concerns that Art Nouveau also objectifies women through use of the othering and the male gaze, but whether those elements outweigh the positive, empowering depictions is up to the viewer.

So, in summary, the art team at Platinum drew upon the alluring stylistic elements of Art Nouveau to help make the game look like nothing else on the market, but the relationship with the art style is also closely related to the story and specific historic trends that were occurring in tandem with Art Nouveau. What are your thoughts, did Bayonetta's art style draw you in or repel you? Is your Japanese better than mine and can you tell if the designers were actually talking about Art Nouveau?

Thanks for reading this far, hope you enjoyed the pretty pictures. If you enjoyed this thread then I'd suggest you check out my last thread on how Breath of the Wild draws upon 19th century painting for its style and scenery.