Tax me if old.

The past five years have seen a huge shift in the way we consume media, as brick-and-mortar stores shift to digital subscriptions. It's been a valuable tradeoff for some, building billion-dollar companies and unlocking huge libraries of music and video for relatively paltry subscription fees, but it's also been a challenge for cities that rely on those businesses for revenue. Now, Chicago wants to take back those missing taxes, and the way it's retaking them has some lawyers up in arms.

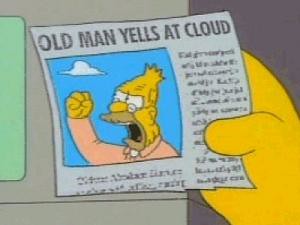

Today, a new "cloud tax" takes effect in the city of Chicago, targeting online databases and streaming entertainment services. It's a puzzling tax, cutting against many of the basic assumptions of the web, but the broader implications could be even more unsettling. Cloud services are built to be universal: Netflix works the same anywhere in the US, and except for rights constraints, you could extend that to the entire world. But many taxes are local — and as streaming services swallow up more and more of the world's entertainment, that could be a serious problem.

Chicago's new tax is actually composed of two recent rulings made by the city's Department of Finance: one covering "electronically delivered amusements" and another covering "nonpossessory computer leases." Each one takes an existing tax law and extends it to levy an extra 9 percent tax on certain types of online services. The first ruling presumably covers streaming media services like Netflix and Spotify, while the second would cover remote database or computing platforms like Amazon Web Services or Lexis Nexis. Under the new law, what passes as $100 of server time in Springfield would cost $109 if you're conducting it from an office in Chicago.

Although the tax is technically levied on consumers, some companies are already preparing to collect it as part of the monthly bill. Netflix says it’s already making arrangements to add the tax to the cost charged to its Chicago customers. "Jurisdictions around the world, including the US, are trying to figure out ways to tax online services," said a Netflix representative, reached by The Verge. "This is one approach."

The result for services is both higher prices and a new focus on localization. For the web services portion, the most likely effect is simply moving servers outside of the city limits — and, where possible, the offices that use them. Once implemented, streaming services will also have to keep closer track of which subscribers fall under the new tax, whether through billing addresses or more restrictive methods like IP tracking, which is already used to enforce rights restrictions.

Some lawyers have already taken issue with the city's move. After the rulings were announced, Reed Smith partner Michael Wynne argued the taxes violate both the Federal Telecommunications Act and, in the case of the second ruling, 1998's Internet Tax Freedom Act, intended to prevent discrimination against services delivered over the internet. "I could do that same activity of research using books or periodicals without being taxed," Wynne says. "So it does seem like I'm being picked on because I chose to do it online."

But while the law may seem onerous, it's also a response to an increasingly difficult reality for cash-strapped cities, particularly as online services start to take a bite out of the businesses in the urban center. Twenty years ago, the same albums and movies were consumed at video rental outlets and music stores — which paid local property taxes, potentially paired with municipal sales taxes and other brick-and-mortar duties. But as online subscription services take over more and more of our music and video budgets, that money ends up disappearing from the traditional municipal tax base. By 2015, the people of Chicago are being entertained by corporations outside of the reach of the city government, leaving it scrambling to make up the difference. Facing a severe budget shortfall, it's easy to see how a city might look toward online services to fill the gap.

Still, the net result for cloud services and customers alike is a confusing hodgepodge. If taxes like Chicago's become widespread, it could become a persistent problem for services like the newly launched Apple Music, which hope to tempt listeners away from ad-supported services like Spotify’s free tier. It would also mean further monitoring on where media is being consumed, which would mean the experience of using a VPN to watch a US-only video might be a harbinger of things to come. In the meantime, the law world is struggling to piece through what the old laws will really mean for the cloud. "There's no question that the city needs revenue and I can see where things are escaping the old tax base," says Wynne, "I think the objectionable part is that, instead of drafting new laws for that, we're simply stretching the old laws to fit."