What people associate as manga/anime style of drawing is not quite a stylistic preference but an economical one. American comic artist have a luxury to spend a week on a page. Japanese comic artist have to continuously produce about 20 pages a week for one title, while coming up with a story at the same time. Some do 80 pages a week for multiple titles but such output require use of assistants. Another related reason for cartoony look is because stylised face are much easier to emote than photo-realistic face. Manga artist have to cheat, skip and economise a lot to keep up with deadline. (

Why do my art teachers hate it when I draw anime? What's wrong with it?). On the other hand, American comic characters by large are no longer cartoony like below because both Marvel and DC franchise are now driven and defined by Hollywood.

So for many Westerners, this villan

is no match for

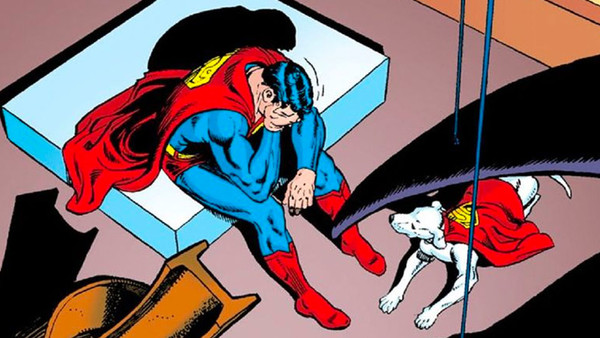

I, on the other hand, am opposite. I can read English. And I (and most Japanese) greatly appreciate Hollywood reincarnation of comic superheroes. Many Japanese get interested in American comic due to their exposure to films. Yet, I (and most Japanese) find American comic nearly unreadable. It is not that I'm blind to visual details of their illustration. I, personally, actually don't like anime in general (with some exceptions) precisely because it is even more cartoony than manga, and anime are often mere deliberative of manga. I am also aware of Graphic novel genere. I liked the film version of Watchmen, and the plot of

Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?

read great. I can also see the artistic merit of Frank Miller's Sin City. But I found American comic too painful to read.

Firstly, I have to READ Western comic while I VIEW manga. The term graphic NOVEL is quite apt. There are just too many text per frame in Western comic.

The above frame is an extreme but not so uncommon example. It has unbelievably dense amount of text for a single frame. I can appreciate illustration is very nice but I really don't want to go through that amount of text for one single frame. Manga is other way round. It is frame heavy and text light.

Manga usually keep text at minimum unless author deliberately want viewers to fix their eyes on a specific frame. In such instance, scene is meant to be stationary for the length it takes to read text. For example, the below is where a character is having a monologue in his head. Then manga author want the viewers to feel as if they are mindreading the character. Lack of speech bubble further reinforce the impression that text is thought of the character.

Clever manga artist use technique like below to make viewer read large amount of text. An evil monologue by a villan is split into three panel to give a quiet sence of tempo.

But in the below comic for wonder women, there are more than an issue of dense text. It is a quick motion of punch up action scene with "CHUKK" "CHOK" "PAK" and "KRAMMMM". So why is she conversing with the monster at the same time for a minute? Seriously, if I'm just viewing the page, my eye just zig (left to right then down) in few seconds. Action scene and conversation scene are completely out of sync.

Compare that with the below manga. Two pages illustrate a whole sequences of combat, while introducing another sequence in the next page with an imminent collision into a building. (Japanese comic read from top right to bottom left) Also notice how frames are cut diagonally and are in different size to punctuate the action as well as to indicate the correct direction of zig and zag.

The above dynamism in manga is credited to one person,

Osamu Tezuka

, father of manga as we know it. He was a medical doctor by training but he only trained to become a doctor to avoid military draft. He also had hemophobia (he was afraid of blood). So he didn't want to practice as a doctor, and tried to make a living by what he actually liked, comic. He was an avid fan of Disney animation so he attempted to animate his comic by doing below in 1947.

In the above spread, there is not a text, not even onamatapea of brooom. But you can see the speed of car and hear the sound of engine and even feel the dust the car leave behind. He is widely regarded as someone who introduced "cinematic technique" in comic medium, but this statement is widely misunderstood in West. He did not invent cinematic "angle" (camera shot) in comic. Quite few comic artists were doing just that before him. What he did was to synchronise size, shape, placement and sequence of frames with reader's eye movements to create a sense of dynamism and drama within sequence of static pictures.

Let me demonstrate this idea of "time syncing" by showing how not to do this in the below, which is another example of beautiful illustration from American comic with great cinematic angle.

Frame 1: So Superman is descending to the ground, and that the scene is captured from sideway camera in long distance.

Frame 2: Instead of the camera then closing in on the superman following him going down, the camera suddenly switch to the location below him, looking up at him. Not only that, instead of Superman's head pointing 5 o'clock south east direction (which would indicate he is still descending), his head is, instead, pointing 2 o'clock north east, flying away from fire in the background, which give an impression that he is now either ascending or flying side way.

Frame 3: But oh, wait, the camera switch back to chasing mode. So he is still descending. Also, it seems that I missed the part where he flipped so that his leg is now pointing down ready to land. Also, I can't see the other person who is speaking to superman. And lastly, text is bit too long up to this point because that give an impression that superman has been gliding down in leisurely pace but the red line in the first frame should mean that superman is going down really fast. This is another example of text and frame being out of sync.

Frame 4: Frame 1 and 3 gave me an impression that superman was descending diagonally from left to right, but now in this frame he descended from top right to bottom left because camera flipped again. I personally prefered that camera chased Superman, and then, as he land, the camera also land behind Superman and rotate and face sideway, capturing superman's back on the left of the frame, closer to the camera and catching the batman on the right, further away from camera. Also, if the superman's back is facing the camera while batman's front is facing the camera directly, the sequence of scene would naturally shift viewer's focus from Superman to Batman.

Frame 5: I'm nitpicking here but if one want to close up on Batman's face from frame 4, then you should just rotate the camera to right, which continue well to the next frame where someone is entering from the right with the dialogue "nothing is simple", where the camera can keep rotating to right. (Also, why is superman suddenly standing so close to batman, sticking his head like he is photobombing? )

Frame 6 (the main pic): Wow, did Batman just teleport to the left of superman? In the previously frame, Wonder woman entered the scene from the right. And the previous frame 3 appear to confirm that she is standing in the circle podium which is on right. So the camera hasn't flipped like the last time. Now Bruce is located to the left of superman.

I still like how the centerpiece of this page look though. It is a grand entrance of another main character, Wonder woman, with a wide shot which also capture superman and batman with a sense of depth. And with this nice camera angle, all eyes (batman, superman and the readers) are focused on her, announcing her appearance with a line, "None of us do, Bruce".

Wait, what? What does she means by that?

Oh, ok, I should have, instead, moved my eyes to the furthest side of where my attention was naturally directed to, where Bruce is saying "You don't belong here Diana". So not only Batman inexplicably teleported furthest from the position of where people's eyes are focused, he force-rewind time backward for viewer, then make reader/viewer to look at his back on the opposite end of the frame to read his speech, effectively ruining the moment (and momentum) of Diana's grand entrance. I never worked in Tinseltown but if I was a studio execs who see this, I would be like "Who the fuck did this scene? This is worse than a high school project!".

In term of visual details, the above DC comic strips is superb but as a sequential visual scene, it is one big mess of visual mindfuck. Editing is really terrible. Camera flip too often without good explanation. Texts are out of sync with the direction of eye movement.

If I was to fix this, I would have made superman fly from sideway from left to right, instead of descending from top to down. So in the fourth frame where the camera is behind Batman, we should see superman glide down toward camera and Batman instead of coming down from right to left. In the main frame, Bruce should have kept his mouth shut and let Diana say something dramatic straight after "Nothing's simple". Then he should have used "You don't belong here, Diana" line in Frame 7 at the bottom left, and Diana could have countered that in Frame 8 with "None of us do, Bruce".

Compare the above with what Tezuka did in 1947 again. This time, the second half of strip is accompanied by the onamatapea of break being applied.

which has evolved into

https

in 21 century. (Thanks to Geofanny B. Yohanes who provided this in his comment).

But Tezuka did more than making a comic into a graphical conversion of filmed entertainment. His bigger innovation was his radical use of paneling (komawari, lit: frame division).

In the above two pages spread by Tezuka (start from top right and end with bottom left for each page), a guy is looking down a crowd from a terrace, then he spot a lady. His eyes widen with suprise, but she is moving away, he shout out, "Hey!" at the end of the first page. Then in the second page, the conventional paneling break down. The man begins to run into the corner of triangle, down the stairs trying to catch the lady before she disappears. The left page is give impression of urgency and desperation, because the shape of panel make character stretch into narrower corner, where viewer feel squeeze into so-close-yet-so-far sensation. Tezuka's synched not just time but shape, size and placement of frame as a part of dramatisation. This innovative experiment in paneling moved comic away from mere graphical conversion of filmed drama and made it stand on its own as a distinct narrative media.

For example, below is a spread from a very popular high school football/soccer comic in 1980s by another manga writer. There have been several baseball mangas before but this was the first soccer manga which was a mass hit. Baseball is a sport where two teams take turns batting and fielding. It has clear attacking and defending phase, making it easier to dramatise action. (like Charlie Sheen's Major League). Soccer, on the other hand, is a very tricky sport to convert it into a drama because game don't pause, no clear attacking/defending sides, and multiple things happen continuously and concurrently.

So let me explain what is happening with the soccer spread. The story so far is that the hero's team is losing by a point near the end of the game, and the opposition switched to heavily defensive tactics, hoping to carry the game with 1 score advantage. The hero's team is desperate to penetrate the opposition's defensive line but are failing. And to top it off, their (our) striker hero, Tsubasa, has retreated from the front line to the mid field because he sustained injury on his left shoulder and left feet. The hero's team is nearly at wit's end.

1) The first 3 frames on top right is where offensive forwards of hero's teammates are thinking "This is impenetrable", "We gotta change the play", and "Send the ball back to Tsubasa, the gamemaker". While these texts are read sequentially, these are actually viewed concurrently as one single meta frame.

2) So one teammate pass back the ball to Tsubasa (the hero), with thought text saying "You are hurt but we still believe in you", (this is the part where visual line move horizontally from left to right). The speech bubble on the right middle of the page, which have straight geometric shape rather than round bubble is a narrative speech by the commentator, "Wait, they passed the ball backward?!"

3) This is followed by the opponent team's reaction at the bottom of the right page, being taken back by the move. "What!?", "Oh, no!", and the commentator's narrative speech "Look, Defensive side left Tsubasa without a mark! He is moving in!!", which is coupled with the camera shot from the above and the front of our hero moving into the ball.

The camera close up to the face of the hero at the top center of the spread.

Motion lines

of this close up indicate he is moving forward at considerable speed. Hero's mind is shouting "The Dive Shoot! There is an opening at top right of the goal!".

4) The reader's eye then move from the peak to down left direction, this time capturing the full body of Tsubasa making the Dive shoot, his right striking leg almost invisible with speed, about to launch the final Hail-Mary attack with his super shot (it goes over the defence super fast yet just before the goal, the ball suddenly dive down, making it almost impossible for any goalie to intercept. Complete fictitious super shot but the main audience was pre-teen.) At the same time, there are two onomatopoeia placed on the left shoulder and his left foot indicating his injured body parts creaking and being almost at breaking point. Also, the commentator is screaming with two speech bubble around the hero's legs, "HE IS GOING FOR THE GOAL!!" and "CAN HE DO IT?!", Then the last frame point to the opponent's goalie (sorta rival/villain in this comic) shouting "Bring it on!! My right hand will stop it." which then lead to the next new spread.

In this spread, physical actions, psychological drama and dialogue and narrative commentary are presented concurrently in one single visual spread and characters are literally breaking out from their frames. Even though this spread contain 10 frames and packed with relatively large amount of text, there are actually only 3 meta frame separated by two blue lines shown below and four classical narrative phase, 1. Arising, 2 Movement, 3 Turning, and 4 Convergence (

Kishōtenketsu

) shown by the red lines. This narrative presentation is no longer a pictorial presentation of filmed scene which are sequential in nature. Multiple thread of drama are presented simultaneously in one spread. I actually hated the animated version of this comic because character's thought, dialogue, narrative commentary, once put in animated sequence were too long, and it killed the pacing of action. (I rarely like animated version of any manga.)

The above is no longer a sequential linear narrative typified by film. The comic, with its dynamic use of paneling, can pack multiple thread of dramatic development into one single spread. This make comic as an unique narrative medium separate from novel and from film. So when I see a panelling like the below, it is a real eye sore. It is painfully flat. It is as if a film was merely made by fixing a camera in front of a theatre stage. And the camera never move, no close up or long shot.

And to top it off, American comic usually show very little sense of dialogue (and emotion which come with it). For example, below strips is something which recently came up on BBC about wonder woman finally coming out as a bisexual. I really likes the eyes/looks of Diana in the 1st frame, which is sad but empathic and caring. I have usual complaint here about the blonde woman talking too long in one single frame. But my biggest complain is that this scene could be so much more.

Contrast the above strip with the below one spread (two-page) fanfiction of

Doraemon

, which went viral in Japan.

Frame 1 Doraemon: "Nobita-kun"

Frame 2 Nobita: "What is it?" (Nobita in real comic is a boy in a primary school. In this fanfiction, he is a wrinkled grey haired adult.)

Frame 3 Doraemon: "We could still do stuffs. We could go anywhere, and fly everywhere, just like old days." (Doraemon is a gadget bot, and his two main gadgets are teleportation door and flying helicopter cap, which come out of his subspace pocket located on his tummy, visible in this frame.)

Frame 4 Nobita: "I don't need gadgets…. as long as you are here." Doraemon: "Is it so……".

Frame 5 Nobita: "Let talk instead, about old days until I fall asleep." "Will you, please, Doraemon?"

The next page is

Frame 1 Dorami: Welcome home brother. (Dorami is Doraemon's younger sister. She live in the future so we know that Doraemon is now back in the future. )

Frame 2 Dorami: "Have you said goodbye to him?" Doraemon: "Yep".

Frame 3 Drami: "I see, so you are not going back to that time era". Doraemon: "Nope".

Frame 4 Draemon: "Nobita won't be there". Frame 5 Draemon: "He is gone forever……"

Now, at this point, everything in the first page make sense. Page 1 was in the hospital, and Nobita was in his deathbed. The strip could have started off by something looking like the fourth frame and repeats that camera shot with dialogue back and forth. That would be similar to Wonder Woman's strips. Instead, viewers are introduced to 3 close up frames, which give unusual angle of Doraemon talking to Nobita while facing away from him and looking down at his own hand because Doraemon can't bear to look at Nobita. And he is still trying to make adult Nobita happy like old days with his gadget because he doesn't know what else to say in this situation. Nobita, on the other hand, has already accepted his fate. He can look directly at Doraemon and he is no longer concerned with gadgets. He still make a wish like he does in every episode but of different kind today.

In the Doraemon strip, impending death is implied but not mentioned. Awkwardness of two are also expressed by Doraemon looking away, and the whole frame sequence gently push viewers' focus downward toward Doraemon's hand which Nobita physically and emotionally touch at the last frame, with the signature one liner "Please, Doraemon" of this manga series. Just this time, it is the final wish. Also, notice that pencil drawing is deliberately rougher and shadow deeper in the last hand holding scene because, when Nobita say his signature one liner, the time froze for a brief moment for two of them. This is an effective comic writing despite being show in B&W toons.

Imagine, what is unsaid in the above is explicitly explained by dialogue. Doraemon: "Nobita-kun, Aren't you afraid of dying?" Nobita: "I have accepted my fate. Let's talk instead about old time." Not only this version of dialogue mention the unmentionable "D" word, Doraemon ask directly to Nobita as if he actually doesn't care. Similarly, the blonde one in Wonder woman strips says "And that would break my heart" out loud. So we know she actually doesn't care. She is "disappointed' for sure but obviously it is no big deal for her. Also, when she explicitly spelt out that "You sacrifice your place in paradise and everything that come with it", Diana's sacrifice actually doesn't sound that bad. The wonder woman dialogue is flat and the scene has no emotional depth. The reader won't feel the pain of separation.

It is Film Study 101. If something have to be explained to audience by words, then film maker is not doing a good job. Also, it is Creative Writing 101. If, for example, you are going to describe a scene where a beautiful woman walk into a room, then do not describe her as "beautiful". Describe how her hairs shine or how long it is, depth of her stare, her eye brow/lash, her poise, or stunned reaction of people in the room, but don't mention the B word, because that will kill the mood. American comic characters don't usually have proper dialogue because they are too busy explaining what is going on to readers so to fill the gap between pictures.

Contrast this with collection of no-speech manga from around the world

セリフなし。絵と演出力で勝負するマンガコンテストが凄い - NAVER まとめ

Press Center

(Winners get their comic animated or transformed into short film.

SMA01.

SMA02.

SMA03.

SMA04.

SMA Extra Round 2016.

SMA05.

SMA6.

SMA Extra Round 2017

)

So to answer the original question, American comic has very high production value compared to manga. Characters' body and face are anatomically accurate and sculpted like greek statue and background drawing is also grand, all in high details and in colour. Plots are often serious, real and art. Overall, American comic looks superb. Yet, characters don't move, they don't emote, dialogues are in-your-face awkward, camera works is terrible and editing has no sense of how the reader view the spread. This is all because American comic are essentially illustrated story book for adult.

Japanese manga, on the other hand, have terrible production value as illustrative art. It is essentially B&W drawing with Mickey mouse characters printed on recycled papers which get thrown away like old newspaper. Yet characters can properly emote, action are dynamic, drama have dialogue with proper subtlety (well at least good manga do), and crucially for comic, all story are narrated visually rather than by text. You feel sound, action and emotion in manga. And it is not just a knocked off version of a movie, but it can narrate story in a way only comic can.

And there is really no need for American comic to be stuck in its current paradigm as illustrative art. Current direction of making comic as collector's item is making matter worse because more time and effort is spent on smaller number of illustrations to make illustration looks pretty, while texts had to be used liberally to fill in narrative gap. There is a huge gap in creative outlet for Westerners who aspire to be storyteller. You either write novel or write screenplay (direct). And filmed medium is generally prohibitively costly. In Japan, manga as a graphical story stand between written story (i.e. novel) and filmed story (i.e. TV/Movie/Animation). Comic can match any genere in novel or film yet the cost of producing a manga story is as cheap as writing a novel, especially with the advent of PC. Many manga author start making manga when they are in high school because anyone, including those who cannot draw well, can create manga.

American comic does not need to ape disney/manga/anime style of character to transform their medium to narrative art. Big eyes characters are secondary effect of weekly production deadline, and is not what manga (and comic) is about. The essence of comic is in its panelling (

komawari

) and not the style of illustration. Also, American comic artists would have advantage of not being constrained by by b&w presentation of Japanese manga, which is tied to Japanese specific issue of being pulp fiction. Hopefully, someone find a way to fill the gap which exist between filmed and written narrative story in English media (and preferably do so in colour). Manga just means comic in Japanese.