MIT Technology Review

The first known attempt at creating genetically modified human embryos in the United States has been carried out by a team of researchers in Portland, Oregon, Technology Review has learned.

The effort, led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov of Oregon Health and Science University, involved changing the DNA of a large number of one-cell embryos with the gene-editing technique CRISPR, according to people familiar with the scientific results.

Until now, American scientists have watched with a combination of awe, envy, and some alarm as scientists elsewhere were first to explore the controversial practice. To date, three previous reports of editing human embryos were all published by scientists in China.

Now Mitalipov is believed to have broken new ground both in the number of embryos experimented upon and by demonstrating that it is possible to safely and efficiently correct defective genes that cause inherited diseases.

Although none of the embryos were allowed to develop for more than a few days—and there was never any intention of implanting them into a womb—the experiments are a milestone on what may prove to be an inevitable journey toward the birth of the first genetically modified humans.

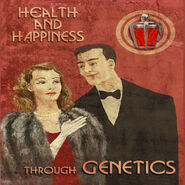

In altering the DNA code of human embryos, the objective of scientists is to show that they can eradicate or correct genes that cause inherited disease, like the blood condition beta-thalassemia. The process is termed "germline engineering" because any genetically modified child would then pass the changes on to subsequent generations via their own germ cells—the egg and sperm.

The earlier Chinese publications, although limited in scope, found CRISPR caused editing errors and that the desired DNA changes were taken up not by all the cells of an embryo, only some. That effect, called mosaicism, lent weight to arguments that germline editing would be an unsafe way to create a person.

But Mitalipov and his colleagues are said to have convincingly shown that it is possible to avoid both mosaicism and "off-target" effects, as the CRISPR errors are known.

...

"It is proof of principle that it can work. They significantly reduced mosaicism. I don't think it's the start of clinical trials yet, but it does take it further than anyone has before," said a scientist familiar with the project.

The report also offered qualified support for the use of CRISPR for making gene-edited babies, but only if it were deployed for the elimination of serious diseases.

The advisory committee drew a red line at genetic enhancements—like higher intelligence. "Genome editing to enhance traits or abilities beyond ordinary health raises concerns about whether the benefits can outweigh the risks, and about fairness if available only to some people," said Alta Charo, co-chair of the NAS's study committee and professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.