Read most of the thread, and it is unclear to me how well these methods work on more technical studies (i.e. Maths, engineering or sciences related studies. As opposed to history or psychology or whatnot). Most of it seems relevant, but it does not seem exact. What needs to be modified?

Also, I recently started studying maths in uni after not having done so since highschool (a little over five years ago). I found that while I did remember the basics (derivatives, integrals, etc) I could not explain what I did and could not do very difficult problems.

I then viewed online a series of lectures which proports to be "understanding based" (even going back to the most basic math) attempting to get students to understand rather than memorise, etc. (though formulas cheatsheets and calculators are still not allowed). It, along with fitting problems, mostly mixed from different topics, did wonders. I now understand the material better than I ever have, and can much more quickly assimilate new knowledge. I often forget formulas and the like but I now have the ability to recreate most of them.

Not sure if that's really related, but this turned maths from something I had neutral to negative feelings about to actually actively enjoying it, as each problem is like a new riddle and I get a real pleasure from actually understanding these things rather than knowing formulas and solution methods by rote.

That is actually well in-line with the research in the book. Memorizing rules and then applying those rules is not very cognitively difficult. You do not understand the underling principle of the rule and do not understand how that rule connects to your growing body of math/scientific knowledge. You do not see patterns.

Moreover, mixing in old problems that you somewhat already know, but are related to that, which seems to be what your class did is very very related. That is the whole concept of interleaving. This makes it so that you can make better distinctions. How do I know how to solve this problem and how to solve this different but somewhat related problems? You do that by working on them 'together' through the process of interleaving.

So yea, your course took a lot of the principles in this book and applied it to your class. I think you might be getting hung up on idea of testing. Basically, what they mean by testing is recall-practice (not review-practice). Recall Recall Recall, and the more cognitive effort you put into that recall, such as seeing patterns, understanding the underlining principle, and making connections to prior knowledge the more that knowledge will 'stick'

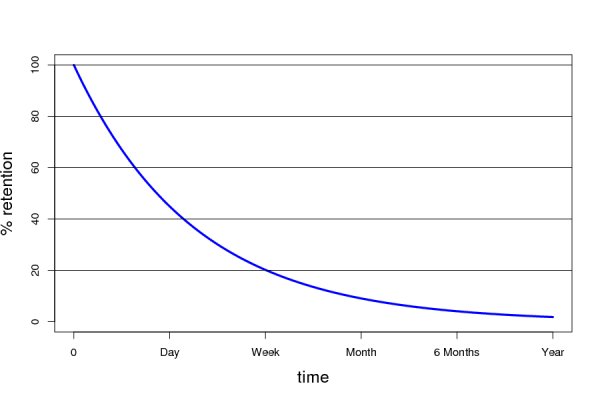

What you should do forward is used spaced-repetition testing if you do not want to forget all of that. If you do not, you most certainly will. I would look into Anki. You can use them as simple flashcards, or flashcards that you will use to force you to recall all of that deeper meaning good stuff. It is up to you. Again, testing in this sense is recalling. No notes, no hints, no nothing. It all comes from your brain. Then get feedback on your answers to make corrections. Then do that sort of practice-recall when you are studying in future math lectures.

Honestly, I think this sort of system works better for math and science, and the like