I'm for getting a Europa spot. There's still a long shot United get 4th if they win out and get some luck. There is always the expectation for a United manager and the squad to perform well in the league, domestic cups, and Europe. Moyes needs to show he can succeed at all these things.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Football Thread 13/14 |OT18| Coming Early by L. Piscium

- Thread starter Lambda Pie

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Broder Salsa

Banned

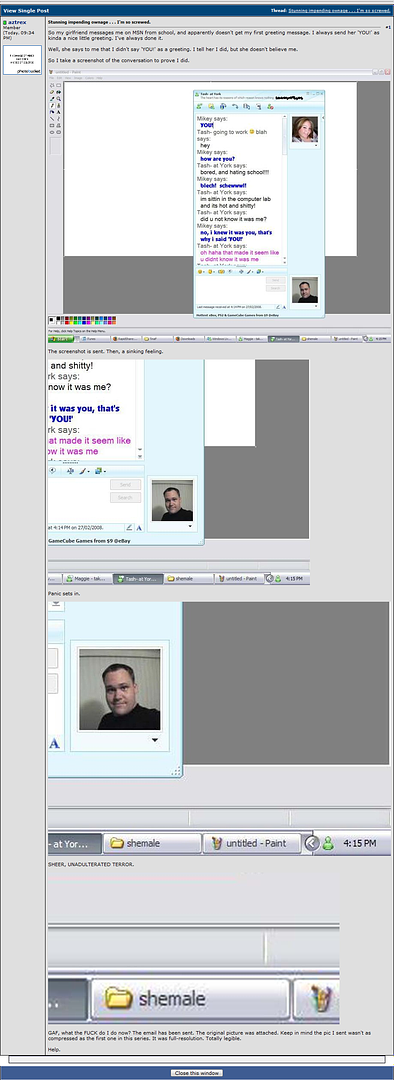

tr**ny is a banned word? Fuck man Gaf has changed. It used to be whenever you posted a screen shot of a website, you always had another tab open with tr**ny surprise or "tr**ny s*ndwi*h" as the title.

Oh God, anyone got the screenshot of that poor guy on GAF who started that meme? Something about him accidentally screenshotting his folder saying tranny surprise and sending it to his girlfriend... I read that historical GAF moments thread or whatever it was called, and there was a link to his old thread. The whole thing ended up on the front page of digg and such... With his face and everything from the MSN convo he had open with his girlfriend. :lol

Then people started searching for his username and found him searching around on everything from that to BBW forums for pussy. I think he still posts on here.

Oh God, anyone got the screenshot of that poor guy on GAF who started that meme? Something about him accidentally screenshotting his folder saying tranny surprise and sending it to his girlfriend... I read that historical GAF moments thread or whatever it was called, and there was a link to his old thread. The whole thing ended up on the front page of digg and such... With his face and everything from the MSN convo he had open with his girlfriend. :lol

Then people started searching for his username and found him searching around on everything from that to BBW forums for pussy. I think he still posts on here.

this is why GAF is creepy

"I have not failed, I have just tried 10,000 things which haven't worked."

Moyes pls.

You're not fucking serious

Broder Salsa

Banned

this is why GAF is creepy

Ah, it actually said shemales. I remembered wrong.

The look on his face. :lool

Thread is still there

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?p=9968715

LabouredSubterfuge

Member

:lol

it was the only suitable word I could think of

The term 'transsexual' is an accepted classification, Dean.

Freewheelin'

Member

^ ahahaha

Best thread ever has to be the JBaird one. Jesus christ what a mindfuck

edit: I'm dumb

pls understand

Best thread ever has to be the JBaird one. Jesus christ what a mindfuck

edit: I'm dumb

pls understand

You're not welcome here without Giggsy.I want Europa League because I want more classic nights in Turin

Or if you're going to wear your shitty Inter-esque away shirts

Oh it was Edison. Sorry vulva.

c h r i s t

See now you know why I'm always on his fucking case

Changing it to "man"

dean i love you

That is utterly fucking phenomenal :lol:lol

c h r i s t

See now you know why I'm always on his fucking case

^ ahahaha

Best thread ever has to be the JBaird one. Jesus christ what a mindfuck

edit: I'm dumb

pls understand

refresh my memory. I forgot what went down.

Told you Dean is the Superior-Rhodes bro ♡Oh it was Edison. Sorry vulva.

c h r i s t

See now you know why I'm always on his fucking case

Broder Salsa

Banned

Told you Dean is the Superior-Rhodes bro ♡

No, that's Lloyd.

Shatner's Bassoon

Member

JBaird was the "go ly dow" right?

Broder Salsa

Banned

JBaird was the "go ly dow" right?

Yes.

Freewheelin'

Member

refresh my memory. I forgot what went down.

the dude who lied about his gf (or sister?) and her friend being lost in the woods or something. So he asked GAF to try and find them but eventually the lie kept getting bigger and bigger and he got caught out. Got instantly perma'd :lol

I'll try and find the thread

Dutch Gronk

Banned

You're all Brits right? Somebody hook me up with Eliza Doolittle her digits.

You're Dutch and you're looking for British girls?You're all Brits right? Somebody hook me up with Eliza Doolittle her digits.

WHY?

Joel Was Right

Member

refresh my memory. I forgot what went down.

One of the greatest moments in internet history. The twists, the turns. JBaird divided the forum into those who believed his gf missing in the woods, and those that didn't.

Police

Tracking IP addresses

Debating the source of the IP address

Debating the validity that he was actually in a police station

Everything was true.

Everything was a lie.

Some to this day still argue that he was telling the truth.

Freewheelin'

Member

The JBaird thread. prepare for insanity

in fact here's an in-depth recap:

in fact here's an in-depth recap:

1. JBaird posts that his girlfriend was driving to Tennessee and police found her car empty and wrecked.

2. GAF sympathizes with OP. Some even offer money and phone calls.

3. JBaird claims that his girlfriend's sister was murdered and raped, but still no sign of his girlfriend.

4. GAF mods determine that he posted from the police station with the same IP address as his home IP address.

5. GAF freaks out, and begins to truly doubt his story.

6. Mods convene and determine that it is possible to have the same IP with a mobile device.

7. JBaird posts girlfriends name, detective GAF goes on the prowl with mod's approval.

8. JBaird's girlfriend is on MySpace, online and alive.

9. JBaird, now caught/confused, doesn't know how that's possible.

10. Amir0x and many others message the girl, but with no response.

11. Amir0x gives JBaird a deal: Confess with minimal punishment or deny and face a permaban if there is no official information.

12. JBaird cries and moans about privacy...when he was the one who posted it all on the forum to begin with. He claims this is all true and does not take the deal.

13. JBaird gets defensive and starts ranting about how his top priority is to ensure the integrity of his girlfriend and his girlfriend's sister and that the mods remove all evidence of who these people are.

14. JBaird admits that the whole thing might not be true and that he might have been duped by his girlfriend.

15. GAF offers advice, and JBaird goes missing for a short while.

We missed you Sir MeusOne of the greatest moments in internet history. The twists, the turns. JBaird divided the forum into those who believed his gf missing in the woods, and those that didn't.

Police

Tracking IP addresses

Debating the source of the IP address

Debating the validity that he was actually in a police station

Everything was true.

Everything was a lie.

Some to this day still argue that he was telling the truth.

Or at least I did!

Dutch Gronk

Banned

You're Dutch and you're looking for British girls?

WHY?

Technically speaking I'm 50% Dutch and 50% 'murican.

And have you seen her? HNNNNNNGGGGGGG

Plus Doutzen Kroes isn't available at the moment.

So much glory in one body.Technically speaking I'm 50% Dutch and 50% 'murican.

Still, go for the Dutch <3

This made me laugh

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=554648&page=23

Detective GAF at work, again!

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=554648&page=23

Detective GAF at work, again!

Freewheelin'

Member

Someone also account suicide'd by making a thread that had nun porn in it :lol :lol

This made me laugh

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=554648&page=23

Detective GAF at work, again!

There's only 12 pages, why have you linked me to a page 23?

PC-GAF has ruined GAF. Tr***** Surprise was a GAF classic.

Gaf is so god damn PC its sucked so much of the fun out of it. It's like the fucking DMV around here.

/spoiler I understand why and I can't disagree with the direction to go toward a more sensitive and all-inclusive direction. But AT WHAT COST?!

Phenomenal article on The Times:

For many years, scientists and anthropologists have pondered the curious phenomenon of home advantage. Why would athletes, paid huge sums of money to win matches, try harder just because a group of strangers are shouting for them? Why would that make a blind bit of difference? Yesterday, at Anfield, we got our answer.

It started early. As the players arrived at the ground on their team bus, they were surrounded by believers. Flags were waved, songs sung, and a sense of possibility filled the air. It was more than an hour before kick-off, but the players were already confronted by a heady set of emotions. Brendan Rodgers, in his pre-match interview, said: Money cant buy what we just felt on the way here. It was about history and passion for our city and our football club.

By the time they arrived in the stadium, Anfield had reached a fever pitch. The proximity of the title, the chance of ending 24 years of pain, explained some of the emotion. But it was about more than that. As the crowd sang Youll Never Walk Alone, the stadium underwent a metamorphosis. It affected everyone: players, managers, referee, perhaps even the millions of TV viewers around the world. Anfield became a cathedral.

I remember once going to Methodist Central Hall to listen to Mozarts Requiem. I am not a religious person, but as the music soared, I became a temporary believer. The experience is not uncommon, apparently, even amongst atheists.

Neuroscientists have noted that the electrochemistry of the brain undergoes a shift when a person is surrounded by a fervent crowd. This hints at the power of stadium evangelism of the kind made famous by Billy Graham. Belief can sometimes be contagious. Yesterday, Liverpool fans made believers of their team. It is often said that the Kop is a twelfth man, but for long sections of a breathless opening, they seemed to be out there on the pitch. Not physically, but in a spiritual way.

The players were feeding off the emotion, finding inspiration in it, hitting passes and trusting the willl of the fans to bend the ball into its optimum path. When Raheem Sterling scored the first I wondered if the stadium announcer would credit the goal to the Kop.

Hillsborough provided the backdrop and context. In the moments before kick-off,, there was a minutes silence, impeccably observed, Joe Corrigan and Mike Summerbee presented a floral tribute: 96 red and blue roses, accepted on behalf of Liverpool FC by Kenny Dalglish and Ian Rush.

A few miles away, a second inquest into the tragedy is unfolding, providing new insights into the lives of those who died, and the ordeal their families have endured. Hillsborough is a living part of Liverpools history. Football is often described as a secular religion, sometimes in a mocking way, but it is an idea that contains many deep truths. Generally it is applied to the fans: their devotion, the liturgy of match day, the cognitive dissonance of always believing that ones team is the greatest in the world, despite the evidence to the contrary.

There is also the aspect of shared experiences, of massed chanting, and of messianic figures (often managers), who will rescue the club and point the way to a new kind of truth. And yet, to my mind, the metaphor is too rarely applied to players. We are often told that the modern breed of player is footloose, unattached, willing to go wherever the cash is. They are agnostics, unaffected by the history and traditions of the clubs they represent, and who kiss the badge, not because they mean it, but for show.

For many players this is doubtless true. Fans are believers while players are mercenaries. The great managers, however, attempt to subvert this idea. They do not merely pay their players; they also seek to evangelise them. They emphasise the history of the club, its meaning in hearts and minds. They recognise that when a player is there in spirit, he is likely to find deeper wells of inspiration. This was a central plank of Sir Alex Fergusons philosophy. Nobody plays for United without understanding what this club means: its history and traditions, he said.

Brendan Rodgers has harnessed this idea at Liverpool, too. In his first week in charge, he saw the iconic This is Anfield sign that Bill Shankly had placed in the players tunnel. When he asked why it was not there any more, he was told that it had been replaced by a new one. He insisted that the original be put back. He also ordered the reintroduction of red nets in the goals, another Anfield tradition. Above all, he has emphasised the role of fans in contributing to the clubs self-belief. They are our greatest asset, he said.

Such intangibles are, of course, no guarantee of success. Football is about conventional things, too: tactics, preparation, high quality players. But, at the margins, intangibles can be crucial. The phenomenon of home advantage speaks eloquently to the power of fans. Theytransmit belief and create a fortress mentality (studies have shown that testosterone levels are higher for home players something anthropologists have linked to the tribal instinct).

Evidence also suggests that a vocal crowd can influence the referee. In his post-match interview, Rodgers paid tribute to Manchester City. He noted the resilience of the team in blue and acknowledged that they had come within an ace of putting the game beyond Liverpools reach. Indeed, there were periods in the second half when City were mesmerising, particularly when David Silva was orchestrating the play.

The match provided another peerless advert for the Premier League. But many will remember yesterdays match, not just for the brilliance of the play, but for the unique atmosphere created by those within Anfield. They yearned for victory even as they mourned 96 of their comrades , lost almost exactly 25 years ago. As Rodgers put it: It was a wonderful atmosphere. On TV it probably sounded loud, but at pitchside, it was just incredible.

I don't know, I just seen it on Twitter earlierThere's only 12 pages, why have you linked me to a page 23?

pls don't shoot the messenger.

pulga

Banned

If I was Evilore, I'd have peeps like Wooden, Wilbs and buduel as mods. Wes is too soft <3

AT THE COST OF THE LOLS OF COURSE

Gaf is so god damn PC its sucked so much of the fun out of it. It's like the fucking DMV around here.

/spoiler I understand why and I can't disagree with the direction to go toward a more sensitive and all-inclusive direction. But AT WHAT COST?!

AT THE COST OF THE LOLS OF COURSE

Baconsaurus Rex

Member

There's only 12 pages, why have you linked me to a page 23?

100ppp ftw

Baconsaurus Rex

Member

yeah needs more master raceGAF isn't PC enough.

Edit: Useless post

I saw what you said. Wes will be furious.

This made me laugh

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=554648&page=23

Detective GAF at work, again!

Okay.

That's it.

I'm going to bed.

I don't even.... I can't.. My body. My breath. It's gone. It's all gone.

Shatner's Bassoon

Member

It's what happens when you make people like Wes mods.

I mean, he gets legitimately upset when you burp. That is the kind of person that rules this thread.

Pah, a well timed burp can almost be as funny as a fart. Problem is anyone can do a fart and be funny. Burping takes a master.

brokenbeans

Banned

I have no idea what's happening!

So sad :lolThis made me laugh

http://www.neogaf.com/forum/showthread.php?t=554648&page=23

Detective GAF at work, again!

Why am I in this forum fucking hell

I though the same :loooolSo sad :lol

Why am I in this forum fucking hell

Dutch Gronk

Banned

Edit: Useless post

Wanna hear a secret?

Mod can see what you post was pre-edit.

Eh, the balance between using a horrible phrase or term jokingly in a group or forum of friends and what others may see as flat out offensive is always tough to police. Don't envy the mods at all.

If I call a LGBT person I barely know a veado I'd get trollied (if they knew what it meant), but in here in this context it's cool i guess if the person understands where it's coming from.

All bout context innit

/Banning words is a slippery slope, but guess you gotta draw the line somewhere

--

Reading vs Leicister today

Should be alright. Can't see reading getting into the playoffs mind.

If I call a LGBT person I barely know a veado I'd get trollied (if they knew what it meant), but in here in this context it's cool i guess if the person understands where it's coming from.

All bout context innit

/Banning words is a slippery slope, but guess you gotta draw the line somewhere

--

Reading vs Leicister today

Should be alright. Can't see reading getting into the playoffs mind.

Wanna hear a secret?

Mod can see what you post was pre-edit.

I don't really mind. Not as if it was anything bad. Just something silly I threw out and retracted when I realised I didn't feel defending that position.

I don't really mind. Not as if it was anything bad. Just something silly I threw out and retracted when I realised I didn't feel defending that position.

99% of my posts get thrown in the trash for exactly the same reason.

In fact I think I'll just toss this one too..

Baconsaurus Rex

Member

You don't get to 19 posts per day with that mentality

- Status

- Not open for further replies.