https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti...-tycoon-life-in-hong-kong-is-harder-than-ever

Mrs. Lau can't help but glance nervously at the calendar. Her next paycheck isn't for a week, and she doesn't have enough money to feed her family of four crammed into her small, government-subsidized Hong Kong apartment. Her husband can't work, and the kids don't understand why their mother keeps buying stale food.

It's an increasingly familiar tale in Hong Kong, a city of soaring skyscrapers and glittering luxury boutiques that's become perhaps the epitome of income inequality in the developed world. Two decades after Britain handed the former colony over to China, its richest citizens -- billionaires such as Li Ka-shing and Lee Shau Kee -- are thriving, thanks to surging real estate prices and their oligopolistic control over the city's retail outlets, utilities, telecommunications and ports. But not people like Lau.

"Hong Kong is an incredibly extreme case of unmitigated inequality, with very little in place to stop it," said Richard Florida, author of "The New Urban Crisis" and a director at the Martin Prosperity Institute in Toronto. "I don't see it as being sustainable. It's not the economics, it's the political backlash. It generates a backlash, and people just get angry eventually."

Hong Kong's struggle to help its citizens improve their lives may represent the greatest challenge to its unique economic model. The city has been lionized for decades by some economists as the closest thing to a free economy, with few regulations of any kind, and no retail sales or capital gains taxes. More than half of Hong Kong's working population, including Lau, live below the level at which they must pay income tax -- and for the minority who do, the standard rate is a low 15 percent.

In some respects, Hong Kong is experiencing a turbo-charged version of the growing divide evident elsewhere. Formerly remunerative manufacturing jobs -- Hong Kong used to be the world's toy-making capital -- have vanished, replaced at one end of the spectrum by highly paid bankers and at the other by low-wage waiters and floor sweepers.

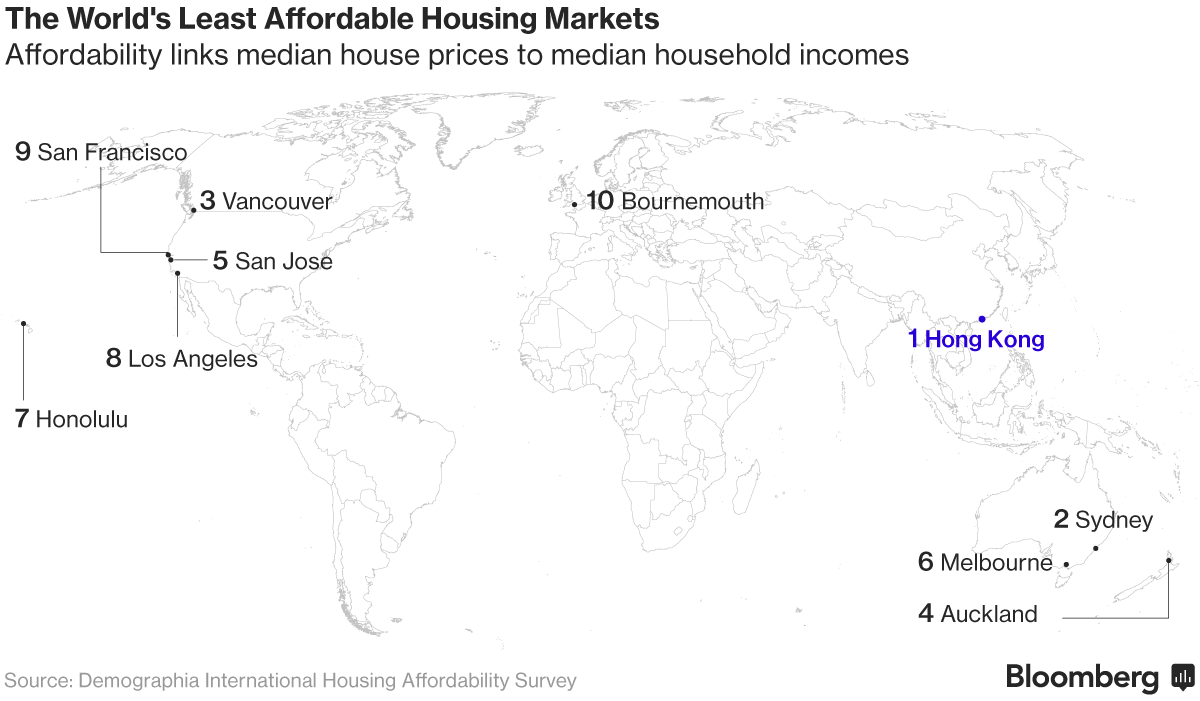

Debates about Hong Kong's rich and poor tend to come back to one word: land. Housing is the least affordable in the world, according to housing-policy think tank Demographia, with median prices relative to incomes far outstripping those of Sydney, London and San Francisco. Home prices have risen nearly 400 percent since a real estate slump ended 14 years ago.

For the middle class, developers have been building an increasing number of micro-apartments, the smallest just 128 square feet, with price tags of more than $400,000.

The assets of the 10 wealthiest people now equal 47 percent of Hong Kong's economy, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Hong Kong continues to construct subsidized apartments. More than 2 million people out of 7 million-plus live in public rental housing paying an average $220 a month. Typically in outlying areas, they feature rows of identical towers of 50 stories or more -- hardly luxurious, but modern and relatively affordable. Still, waiting times can stretch nearly five years.

With living standards lagging behind rising costs, some Hong Kong citizens have begun to wonder what was once unthinkable: whether folks across the border in mainland China might be better off. Take Yu Wen-mei, 61. She started working in a garment factory in the 1970s and recalls ferrying food and appliances to grateful relatives in Guangdong province in the 1980s. As low-end manufacturing disappeared, she took a job in a Motorola plant, which closed in 2000. She's a mall security guard now, earning minimum wage.

"Now, they have everything," she said of her mainland relatives.