Rudolf Brazda, 98, one of the last known survivors of those sent to Nazi concentration camps because they were gay, died Aug. 3 at a nursing home in Bantzenheim, in Alsace, France. The cause of death was not released.

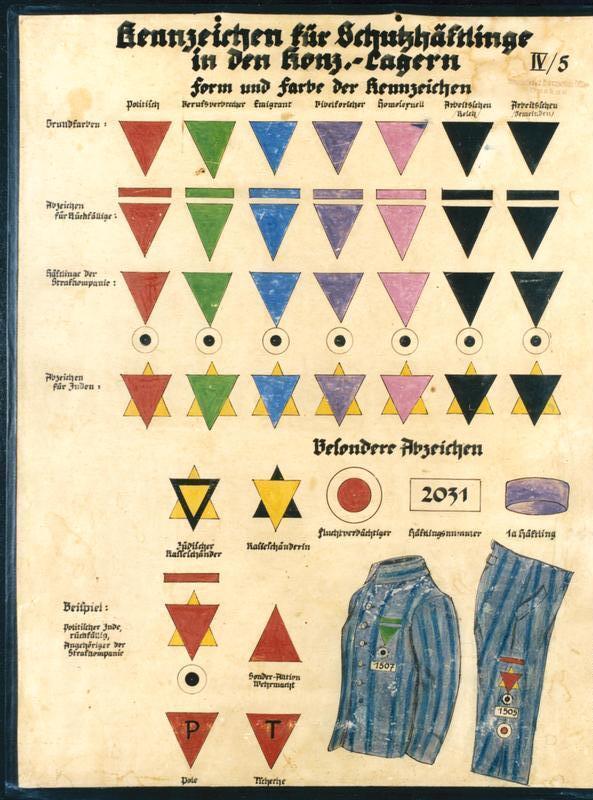

Mr. Brazda, a survivor of the Buchenwald camp, waited more than six decades to tell his story. He came forward in 2008 after hearing about the dedication of a memorial in Berlin to honor pink triangle prisoners the homosexuals deported to concentration camps where, as Jews were forced to wear uniforms bearing stars of David, they were branded with pink triangles.

Before Mr. Brazda emerged, activists thought that the last of those survivors had died.

Few gay victims of the Holocaust spoke about their experiences, said Klaus Mueller, a historian who has documented their stories and who collaborates with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Even after their liberation, society often treated them as transgressors, Mueller said, and they found little empathy for their suffering.

During the Nazi regime, 100,000 men were arrested under Paragraph 175, a German law that criminalized male homosexual acts, and 50,000 were imprisoned. The 5,000 to 15,000 sent to concentration camps endured forced labor so brutal that their survival rate was less than 40 percent.

Alexander Zinn, author of one of two books written about Mr. Brazda since 2008, described Mr. Brazdas decision to share his story at age 94 as a kind of coming out.

Rudolf Brazda was born June 26, 1913, to a Czech family living Meuselwitz, Germany. He was the youngest of eight children in a poor family made poorer when his father died in 1920, but he told biographers that he enjoyed a happy childhood.

In an interview with Der Spiegel magazine not long before his death, Mr. Brazda recalled the summer day in 1933 when he met his first boyfriend. To make his acquaintance, Mr. Brazda said, he flirtatiously pushed the young man into the swimming pool.

A year later, they celebrated an unofficial wedding in the presence of Mr. Brazdas family.

For us looking back, it [seems] very astonishing and modern, Zinn said. He thinks that Mr. Brazda simply didnt understand the perils he would face.

Life in the relatively secluded countryside afforded a measure of freedom in the early years of the Nazi regime, when the Gestapo targeted the gay communities primarily in larger cities. Mr. Brazda moved in with his boyfriend; they were tenants of a woman who belonged to the Jehovahs Witness faith, another group persecuted in Nazi Europe.

As Nazi aggression intensified, Mr. Brazda was in ever-increasing danger. He was arrested twice under Paragraph 175, with love letters and poems presented as evidence of his alleged crimes, before he was sent to Buchenwald on Aug. 8, 1942.

In the camp, Mr. Brazda was sent to a quarry, where laborers stood little chance of survival. A kapo a fellow inmate forced by Nazis to supervise work at the camp released him from that duty and provided for him to work instead in the clinic.

Mr. Brazda avoided almost-certain death again as liberation approached when he escaped a death march by hiding in a pig sty.

Ive always been lucky, he told Jean-Luc Schwab, the other of his two biographers.

After the war, Mr. Brazda followed a fellow inmate to Mulhouse, France, where he remained until shortly before he died. There, he met Edouard Mayer, who would become his partner of more than 50 years, until he died in 2003.

Mr. Brazda left no immediate survivors.

He will be buried Monday, the 69th anniversary of his arrival at Buchenwald. The funeral, Schwab said, will feature a remark that Mr. Brazda made not long before his death:

God gave me the gift of the homosexual life.

Story Here