For all his oppositional tone, Coates turns out to be unable to move beyond Lillas electoralism. This is not because he advocates an electoral strategy, but rather because

his cloak-and-dagger narrative fixates on politicians, using them to symbolize entire political tendencies, analyses, and movements. Socialism appears in Coatess analysis solely as the personal vision of Bernie Sanders, which not only buries the long history of anti-racists who saw socialism as an integral and necessary part of their mission, but also reduces mass movements to famous individuals. What Coates seems to ignore is that political figures are not simply mouthpieces for the unitary views of their supporters, and their supporters are not simply sheep who will fall in line with their supposed leaders every declaration. What was significant about the Sanders campaign were not his personal views or his congressional record, but the fact that a wide range of constituencies with a wide range of demands identified with his call for political revolution. The unique demands of these different groups were made equivalent through their shared opposition to the existing political system.

We now know that black Americans were a fundamentally important link in this chain. Sanders is extremely popular among black votersin fact, more registered black voters view Sanders favorably than any of the other racial demographics surveyed by the Harvard-Harris Poll, and more black voters have a very favorable view of Sanders than they do of Hillary Clinton. Yet, while critical of Hillary Clinton, Coates claims that she acknowledged the existence of systemic racism more explicitly than any of her modern Democratic predecessors.

An effective political practice involves, as Judith Butler puts it, establishing practices of translation between the differing demands of the groups that form a coalition, and eventually finding that

despite any apparent logical incompatibility, these demands may nevertheless belong to an overlapping set of social and political aims. Today, this process of translation has led far beyond the Sanders campaign and the electoral arena in general, with young people seeking out alternative modes of organization and political struggle. Coates, however, is primarily interested in tearing apart Bernie Sanderss language, and thus discrediting those of his supporters who are in the process of discovering new political possibilities. Every comment Sanders makes about identity politics is presented as if it shows the blind spot of any critique of capitalism, as if it illustrates the impotence of class struggle in overcoming white supremacy.

Here once again there is a yawning gap in the narrative. As historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall has demonstrated, it was the black-labor-left coalition of the 1940s which lay the groundwork for the legislative achievements of the 1960s, famously represented by Socialist Party Member, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and core organizer of the 1963 March on Washington A. Philip Randolph. Hall offers us a corrective to the reductive narratives of both Lilla and Coates:

Historians have depicted the postwar years as the moment when race eclipsed class as the defining issue of American liberalism. But among civil rights unionists neither class nor race trumped the other, and both were expansively understood. Proceeding from the assumption that, from the founding of the Republic, racism has been bound up with economic exploitation, civil rights unionists sought to combine protection from discrimination with universalistic social welfare policies and individual rights with labor rights. For them, workplace democracy, union wages, and fair and full employment went hand in hand with open, affordable housing, political enfranchisement, educational equity, and an enhanced safety net, including health care for all.

By ignoring social movements and fixating on politicians,

Coates distorts both the history of mass anti-racist movements and the potential for their contemporary growth. Socialist movements exist in the United States due to the courageous efforts of black socialists, communists, and trade-unionists. It is a legacy which must be carried forward today, and Coates does the struggle against white supremacy an enormous disservice by hiding it behind the liberal contempt for Bernie Sanders.

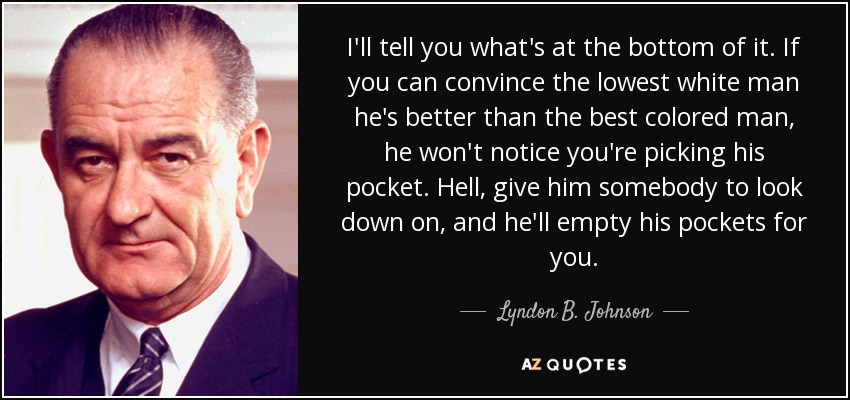

The red herring on which this manipulative narrative turns is the question of the white working class. Coates cites everyone from Sanders to Lilla as apologists for the white working class, whose racism and complicity in Trumps power they deny by pointing to economic anxiety and frustration with elites.

Here Coates makes a peculiar move. He demonstrates conclusively that this argument of Lilla and Sanders is wrong. He points out that a Gallup study of pre-election polling data shows that voters who supported Trump generally had a higher mean household income ($81,898) than those who did not ($77,046), and they were less likely to be unemployed and less likely to be employed part-time. In other words, as Coates correctly concludes, when white pundits cast the elevation of Trump as the handiwork of an inscrutable white working class, they are being too modest, declining to claim credit for their own economic class.

But despite proving that the so-called white working class is not actually Trumps base, Coates insists that for whites, racial solidarity takes precedence over any other political interest, citing the fact that Trumps support was higher among whites as a whole than any other demographic. Once again, this is hardly a stunning new insight, so we have to ask why Coates emphasizes it. It becomes clear, as his argument unfolds, that Coatess goal is to invalidate the possibility of class solidarity across racial boundaries. Even after showing the research which should shatter any belief that this monolith exists, Coates clings to the chimerical figure of the white working class, in order to exclude it from anti-racist struggle.

This is because Coates appears to lack any interest in seeing that struggle succeed. His demand is for moral repentance, not liberation.

But instead of asking whites to feel guilty, we should demand the abolition of whiteness, a project in which they have a responsibility to actively participate. As long as Coates is unwilling to embrace the multiracial mass movement that can abolish whiteness, he and Lilla will forever be left to fight over the throne of a kingdom that remains unchanged. As usual, it is up to the nameless and faceless commoners to make history, rather than to appeal to the conscience of the king.