Spoiled Milk

Banned

My personal take on the lede from a large opinion piece on mass incarceration from Jacobin:

How to End Mass Incarceration

Starts with a story of how we've never been like this before:

Abuse in the prison system:

How it started:

In the 90s:

(Opinion

Some thoughts on racial disparities and the race-centric rhetoric of policing and prison reform:

And finally, on policing:

How to End Mass Incarceration

Starts with a story of how we've never been like this before:

The United States has not always been the world's leading jailer, the only affluent democracy to make "incapacitation" its criminal justice system's goal. Once upon a time, it fashioned itself as the very model of what Michel Foucault called "the disciplinary society." That is, it took an enlightened approach to punishment, progressively tethering it to rehabilitative ideals. Today, it is a carceral state, plain and simple. It posts the highest incarceration rate in the world — as well as the highest violent crime rate among high-income countries.

An American preference for rehabilitative discipline over harsh punishment has deep roots. Resonant with the image of the country as "a nation of laws," American justice promised to punish lawbreakers only as much as was necessary to straighten them out. The Bill of Rights prohibited torture, and the Quaker reformers who founded early American penitentiaries treated them as utopian experiments in discipline, purgatories where penitents would suffer and introspect until they found salvation.

No doubt time and circumstance created different opinions about how much suffering genuine personal reformation required, but American practices generally aligned with rising standards of decency. As James Q. Whitman notes, Europeans once viewed the US prison system as a model of enlightened practices. Foreign governments sent delegations on tours of American penitentiaries, and Alexis de Tocqueville extolled the mildness of American punishment.

Of course, we can find exceptions. Southern penal systems, racialized after the Civil War under the convict-lease system, didn't even pretend to have rehabilitative aims. They existed to control the black population and supply cheap labor for agriculture and industry. No doubt, too, the spectacles of punishment associated with popular colonial justice — the pillory, the stockade, the scarlet letter — cast long shadows across American history.

But, even in the face of these contradictions, the US criminal justice system seemed to support a grand narrative of progressive history: the arc of history bends toward justice, and the slave driver's lash and the lynch mob's noose disappeared as the nation extended more rights and more freedoms to more people. Reasoned law inexorably overcomes communal violence and brute domination.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr thus distinguishes the true essence of the United States from its various manifestations of racism and intolerance, glossing history as the perpetual struggle of Americans to "fulfill their deepest values in an enigmatic world."

Indeed, as a result of the legal reforms of the 1960s, the American prison population was shrinking, and the state was developing alternatives to incarceration: kinder, gentler institutions that focused on supervision, reeducation, and rehabilitation. To many observers, the prison system actually seemed to be reforming itself out of existence. Leo Bersani's review of Foucault's Discipline and Punish began with the (now astonishing) sentence "The era of prisons may be nearly over."

Nothing in Foucault's analysis — or anyone else's, as David Garland has remarked — could have predicted what followed: a sudden punitive turn designed to incapacitate prisoners rather than rehabilitate them. The practice of locking people up for long periods of time became the criminal justice system's organizing principle, and prisons turned into a "reservation system, a quarantine zone" where "purportedly dangerous individuals are segregated in the name of public safety." The resulting system of mass incarceration, Garland writes, resembles nothing so much as the Soviet gulag — a string of work camps and prisons strung across a vast country, housing [more than] two million people most of whom are drawn from classes and racial groups that have become politically and economically problematic.... Like the pre-modern sanctions of transportation or banishment, the prison now functions as a form of exile.

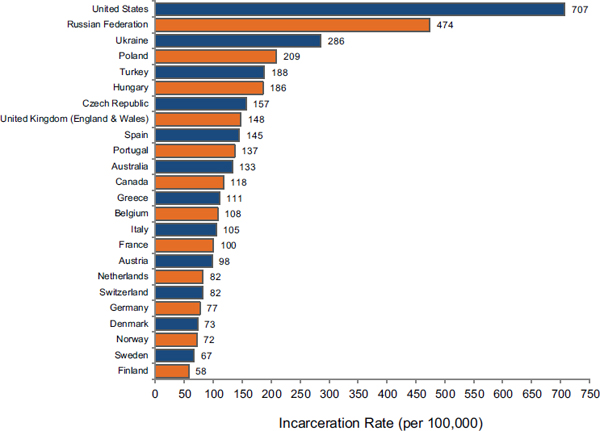

At the peak of this mania, one in every ninety-nine adults was behind bars. Since 2008, these numbers have leveled off and even posted modest declines, but the basic contours remain intact. The United States ranks first in imprisonment among significant nations, whether measured in terms of incarceration rates — which remains five to ten times higher than those of other developed democracies — or in terms of the absolute number of people in prison.

Hyper-policing helped make hyper-punishment possible. By the mid-2000s, police were arresting a staggering fourteen million Americans each year, excluding traffic violations — up from a little more than three million in 1960. That is, the annual arrest rate as a percentage of the population nearly tripled, from 1.6 percent in 1960 to 4.5 percent in 2009. Today, almost one-third of the adult population has an arrest record.

At prevailing rates of incarceration, one in every fifteen Americans will serve time in a prison. For men the rate is more than one in nine. For African American men, the expected lifetime rate runs even higher: roughly one in three.

These figures have no precedent in the United States: not under Puritanism, not even under Jim Crow.

Abuse in the prison system:

In this context, structural abuses invariably flourish. Reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch catalog various forms of sanctioned and unsanctioned human rights abuses. These include beatings and chokings, extended solitary confinement in maximum security and so-called supermax prisons, the mistreatment of juvenile and mentally ill detainees, and the inhumane use of restraints, electrical devices, and attack dogs.

Modern prisons have become places of irredeemable harm and trauma. J. C. Oleson surveys these dehumanizing warehouse prisons, where guards have overseen systems of sexual slavery or orchestrated gladiator-style fights between inmates.

Sally Mann Romano describes shocking brutality in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) of California's Pelican Bay State Prison, once touted as a model supermax prison:

It was in this unit that Vaughn Dortch, a prisoner with a life-long history of mental problems, was confined after a conviction for grand theft. There, the stark conditions of isolation caused his mental condition to "dramatically deteriorate," to the point that he "smeared himself repeatedly with feces and urine." Prison officials took Vaughn to the infirmary to bathe him and asked a medical technician, Irven McMillan, if he "wanted a part of this bath." McMillan responded that "he would take some of the ‘brush end,' referring to a hard bristle brush which is wrapped in a towel and used to clean an inmate." McMillan asked a supervisor for help, but she refused. Ultimately, six guards wearing rubber gloves held Vaughn, with his hands cuffed behind his back, in a tub of scalding water. His attorney later estimated the temperature to be about 125 degrees. McMillan proceeded with the bath while one officer pushed down on Vaughn's shoulder and held his arms in place. After about fifteen minutes, when Vaughn was finally allowed to stand, his skin peeled off in sheets, "hanging in large clumps around his legs." Nurse Barbara Kuroda later testified without rebuttal that she heard a guard say about the black inmate that it "looks like we're going to have a white boy before this is through... his skin is so dirty and so rotten, it's all fallen off." Vaughn received no anesthetic for more than forty-five minutes, eventually collapsed from weakness, and was taken to the emergency room. There he went into shock and almost died.

How it started:

The punitive turn began in the turmoil of the 1960s, a time of rapidly rising crime rates and urban disorder. In 1968, with US cities in flames and white backlash gaining momentum, congress overwhelmingly passed — and Lyndon Johnson reluctantly signed — the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. As Jonathan Simon has suggested, the act became something like a blueprint for subsequent crime-control lawmaking.

...

Although the legislation did little to increase criminal penalties, it reversed the logic of earlier Great Society programs; instead of providing direct investment, the act's block grants ceded control to local agencies, often controlled by conservative governors. Most importantly, the act established the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), an independent branch of the Justice Department. Blaming low conviction rates on a lack of cooperation from victims and witnesses, the LEAA launched demonstration projects aimed at recruiting citizens into the war on crime.

Ironically, the Left was helping to prepare the way for a decisive turn to the Right. Leftist activists from the civil rights, black power, and antiwar movements were leveling heavy criticism against the criminal justice system, and rightly so. Patterns of police brutality had been readily discernible triggers of urban unrest and race riots in the late 1960s, and minorities were overrepresented in the prison population (although not as much as today). Summing up New Left critiques, the American Friends Service Committee's 1971 report, Struggle for Justice, blasted the US prison system not only for repressing youth, the poor, and minorities but also for paternalistically emphasizing individual rehabilitation. Rehabilitate the system, not the individual, the report urged — but the point got lost in the rancorous debates that followed. As David Garland carefully shows, the ensuing "nothing works" consensus among progressive scholars and experts discouraged prison reform — and ultimately lent weight to the arguments of conservatives, whose approach to crime has always been a simple one: Punish the bad man. Put lawbreakers behind bars and keep them there.

In 1974, Robert Martinson's influential article "What Works?" marked a definitive turning point. Examining rehabilitative penal systems' efficacy, Martinson articulated the emerging consensus — "nothing works," and rehabilitation was a hopelessly misconceived goal.

In the 90s:

But liberal rationales also helped the punitive turn put down institutional roots. The victims' rights movement had adopted feminist rhetoric around rape and domestic violence. For example, it claimed that survivors are victimized a "second time" by their unsatisfying experiences with the police and court system. During the same period, mainstream white feminists came to view rape, sexual abuse, and domestic violence through a law-and-order lens and many started demanding harsh criminal penalties. This collusion between conservative victims' rights advocates and white feminists undermined the historic liberal commitment to enlightened humanitarianism and progressive reform, especially as these related to crime and punishment.

In 1994, Democrats aggressively moved to "take back" the crime issue from Republicans, and a Democratically controlled congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. Like the 1968 act, this 1994 legislation pumped a great deal of federal funding into local law enforcement, funding 100,000 new police officers, new prison construction, and new prevention programs in poor neighborhoods. The new legislation also included an assault weapon ban.

Unlike the 1968 act, however, the 1994 version increased penalties for hate crimes, sex crimes, violence against women, and gang-related crimes. It required states to create sex-offender registries and prodded them to adopt "truth in sentencing" laws that would entail longer prison sentences. It also dramatically expanded the federal death penalty and eliminated support for inmate education programs.

The 1994 act completely reversed Great Society penal welfarism, consolidating the punitive approach, which Democrats, liberals, and some progressive advocacy groups now embraced. Indeed, lawmakers drafted many of the act's sweeping provisions with liberal interest groups in mind.

(Opinion

Had the Democratic Party stayed its fundamentally social-democratic course, had it kept with the penal system's reformist program, had the policies of Johnson's Attorney General Ramsey Clark remained in place, and — this is no small matter — had the criminal justice system continued to develop alternatives to incarceration, the United States would not have evolved into a carceral state.

It is of course possible that prison rates would still have risen with the crime rates between the 1970s and the 1990s, but they would not have exploded, and mass incarceration would have remained the stuff of dystopian fiction.

Some thoughts on racial disparities and the race-centric rhetoric of policing and prison reform:

Finally, sociologists, criminologists, and critical race scholars have closely scrutinized the racial disparities in arrest, prosecution, and incarceration rates. Many conclude that mass incarceration constitutes a modern regime of racial domination or a new Jim Crow.

This perspective highlights important facts. While African Americans make up only 13 percent of drug users, they account for more than a third of drug arrestees, more than half of those convicted on drug charges, and 58 percent of those ultimately sent to prison on drug charges. When convicted, a black person can expect to serve almost as much time for a drug offense as a white person would serve for a violent offense.

These statistics demonstrate how race-neutral laws can produce race-biased effects, especially when police, prosecutors, juries, and judges make racialized judgments all along the way. Needless to say, had the mania for incarceration devastated white middle- or even working-class communities as much as it has black lower- and working-class communities, it would have proved politically intolerable very quickly.

But the racial critique consistently downplays the effects of mass incarceration on non-black communities. The incarceration rate for Latinos has also risen, and the confinement and processing of undocumented immigrants has become especially harsh. And although white men are imprisoned at a substantially lower rate than either black or brown men, there are still more white men in prison, in both raw and per capita numbers, than at any time in US history.

In mid-2007, 773 of every 100,000 white males were imprisoned, roughly one-sixth the rate for black males (4,618 per 100,000) but more than three times the average rate of male confinement from the 1920s through 1972. As James Forman Jr argues, the racial critique's focus on African American imprisonment rates expressly discourages the cross-racial coalitions that will be required to dismantle mass incarceration.

And finally, on policing:

We might make a similar argument about the racial critique of abusive policing, which highlights important injustices but fails to provide a comprehensive picture of the whole system. Police do kill more black than white men per capita, a disparity that only increases in the smaller subset of unarmed men killed in encounters with police. But in raw numbers cops kill almost twice as many white men, and non-blacks make up about 74 percent of the people killed by police. We cannot dismiss these numbers as "collateral damage" from a racialized system that targets black bodies.

Examining the profile of these unarmed men is revelatory. Statistically, an unarmed white man has a slightly smaller chance of being killed by law enforcement than he does of being killed by lightning; an unarmed black man's is a few times more. In either case, these rates are many times higher than in other affluent democracies, where violent crime rates are lower, the citizenry is less armed, and police — if armed at all — are less trigger-happy.

Whether black or white, the victims of police shootings have a lot in common: many were experiencing psychotic episodes — either due to chronic mental illness or drug use — when the police were called. Many had prior arrest records or were otherwise previously known to the police. Whether black, white, or brown, the victims of police shootings are disproportionately sub-proletarian or lower working-class.