Wealth taxes are very tricky though, because wealth is flexible and illiquid. Last June the Chinese stock market lost $1.5 trillion in 3 weeks (that's more than the entire annual GDP of Mexico). So various share holders in China and elsewhere lost that much wealth. But that didn't really lose any actual thing. If you owned 20% of the shares in FoxyPhone and they were worth $300bn, then the market crashed and they tumbled in value to $100bn, you just lost $200bn - yet you still own 20% of FoxyPhone. The amount of the business you own is still the same. The business hasn't even changed, just other people's valuation of it. And that's the thing that's a bit difficult to grasp sometimes about wealth - wealth isn't money, it's simply other peoples' valuation of the worth of what you own. You buy a house in Ireland for 400,000 euros in 2006 and now it's worth 120,000 euros, but the house is the same. The only thing that changed is how much other people are willing to pay for it.

But imagine this scenario (and this happened to literally millions of people across Ireland, Spain, Greece etc after the creation of the Euro all the way up to today) - you buy a house for 100,000 euros. It rises and rises and rises in value as the property market inflates and before you know it that house on the edge of Dublin or by the sea in Estepona is worth 500,000 euros. Jubilation! But, well, it's your house and you live there, so as nice as it is that the value's gone up, it doesn't actually do you any good because you don't have that money - you just have the same house that used to be worth 100,000. Now what's happened? There's a world recession, banks stop lending which mean people stop buying houses which means that suddenly the over-saturated housing market shits the bed - no one wants to buy your house for 200,000 euros, much less than 500,000 euros it was worth just before the recession! Now the house is back down to 100,000 again. So during all this time, the owner's net worth ballooned to about three quarters of a million dollars, and has now crashed back down to just over $110,000 - yet the person didn't do anything, didn't get any benefit from this rise, didn't get a better house and didn't gain in any way.

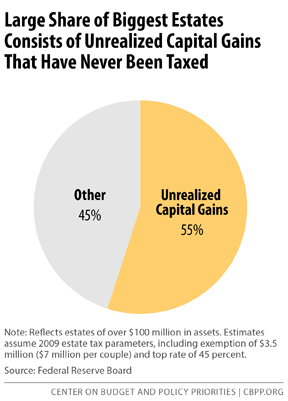

This is a fairly relatable story about housing, but the same theory applies to investing in businesses, physical objects (artwork, classic cars etc). This is why wealth taxes are tricky - at what point would it have been reasonable to ask that Irish/Spanish/Greek house owner to pay the government money, even though they weren't benefiting? And would they have got that money back when the property lost its value again? (Businesses can do this by offsetting profits and losses, since a year is basically an arbitrary period of time over which to calculate taxes). This is why we tend to tax capital gains (the difference between what you buy something for and then what you sell something for) and dividend (payments from a business you own a part of) - because that's when the money actually becomes tangible to you.

All of this is also why looking at the wealth of the 1% is, whilst interesting, not as illuminating and useful as the massive graphs showing the disparity make it seem.