IbizaPocholo

NeoGAFs Kent Brockman

Hidetaka Miyazaki Sees Death as a Feature, Not a Bug

Miyazaki has created the most difficult games of the century. In his latest, Elden Ring, he wants a broader audience to feel the pain.

Dark Souls and its sequels have become notorious for their ego-skewering difficulty. Their reputation transcends video games: "The Dark Souls of 'X' '' is a meme used to describe any particularly onerous task. (A teetering pile of dirty plates? "The Dark Souls of washing up.") "I've never been a very skilled player," Miyazaki told me recently, via Zoom. He was sitting in his office, a book-lined room in the Shinjuku ward of Tokyo. "I die a lot. So, in my work, I want to answer the question: If death is to be more than a mark of failure, how do I give it meaning? How do I make death enjoyable?"

Still, for every vanquisher of Miyazaki's monsters, there's another who glumly sets down the controller. "I do feel apologetic toward anyone who feels there's just too much to overcome in my games," Miyazaki told me. He held his head in his hands, then smiled. "I just want as many players as possible to experience the joy that comes from overcoming hardship."

Miyazaki had played games in his youth, but the moment of discovery arrived around 2001, when, at the urging of friends, he tried Fumito Ueda's Ico, an exquisitely minimalist fairy tale about a boy, a girl, and their escape from a castle. For Miyazaki, the game reproduced the childhood joy of piecing together a story from snippets of text and mysterious illustrations. He decided to switch careers. At twenty-nine, and with no relevant experience, he took a significant pay cut to join FromSoftware, an obscure studio based in Tokyo. He started as a coder, then took over development of a struggling project—a fantasy set in a shadow world of looming castles and eldritch monsters. He rewrote the game from the cobblestones up, creating a mechanism by which, if a player died, they returned to the level's beginning, with their health weakened, their resources lost, and their enemies just as strong. "If my ideas failed, nobody would care," he told me. "It was already a failure."

A theory suggests itself: the challenging circumstances of Miyazaki's early life, followed by a string of hard-won achievements, provided the template for the emotional trajectory that many players experience in his games. Miyazaki—whose face, behind his glasses and wispy goatee, is youthful and jocular—resists the idea. "I wouldn't say that my life story, to put it in grandiose terms, has affected the way I make games," he said. "A more accurate way to look at it is problem solving. We all face problems in our daily lives. Finding answers is always a satisfying thing. But in life, you know, there's not a lot that gives us those feelings readily."

Miyazaki's work is often invoked by the latter camp, as it suggests that challenge, not escapism or uplift, is the medium's crucial quality. "It's an interesting question," Miyazaki told me. "We are always looking to improve, but, in our games specifically, hardship is what gives meaning to the experience. So it's not something we're willing to abandon at the moment. It's our identity."

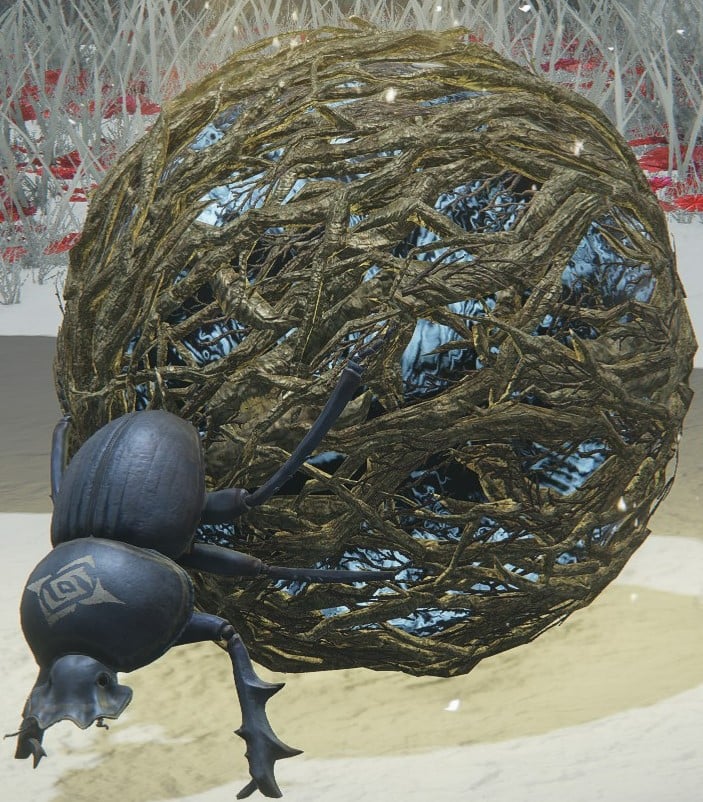

And yet Elden Ring, Miyazaki's new game, offers something of a compromise, a way "for people to feel like victory is an attainable feat," he said. All of his hallmarks remain—the dramatic encounters with giant foes, the demanding combat, the insistence that the player improve their own abilities, rather than merely power up their onscreen avatar—but there are concessions that make the game more approachable. Now you can summon spectral animals to your side, or ride your horse to flee a losing fight. In Miyazaki's previous games, a player was consigned to a handful of given paths, each one blocked by a powerful boss. In Elden Ring, the world is truly open. If one path proves too challenging, you can simply pick another.

Still, you die a lot: in the white heat of a dragon's snort, under the cold weight of a giant's hammer, whipped by the leg of a beached octopus. For Miyazaki, video-game death is an opportunity to create a memory, or a punch line. "When I'm playing these games, I think, This is the way I'd want to die—in a way that is amusing or interesting, or that creates a story I can share," he said. "Death and rebirth, trying and overcoming—we want that cycle to be enjoyable. In life, death is a horrible thing. In play, it can be something else."

For Elden Ring, Miyazaki collaborated with one of his heroes, George R. R. Martin—whose work, he told me, he enjoyed long before fantasy novels such as "Game of Thrones," when Martin was best known as a science-fiction writer. Miyazaki approached Martin at the urging of one of FromSoftware's board members, and was surprised to learn that Martin was a fan of his games. At first, Miyazaki feared that the language barrier and age gap—Martin is seventy-three—would make connection difficult. But as their conversations progressed, in hotel suites or in Martin's home town, a friendship bloomed.

Miyazaki placed some key restraints on Martin's contributions. Namely, Martin was to write the game's backstory, not its actual script. Elden Ring takes place in a world known as the Lands Between. Martin provided snatches of text about its setting, its characters, and its mythology, which includes the destruction of the titular ring and the dispersal of its shards, known as the Great Runes. Miyazaki could then explore the repercussions of that history in the story that the player experiences directly. "In our games, the story must always serve the player experience," he said. "If [Martin] had written the game's story, I would have worried that we might have to drift from that. I wanted him to be able to write freely and not to feel restrained by some obscure mechanic that might have to change in development."

There's an irony in Martin—an author known for his intricate, clockwork plots—working with Miyazaki, whose games are defined by their narrative obfuscation. In Dark Souls, a crucial plot detail is more likely to be found in the description of an item in your inventory than in dialogue. It's a technique Miyazaki employs to spark players' imaginations, in the same way that he extracted stories from illustrated fantasy books as a child. "That power of imagination is important to me," he said. "Offering room for user interpretation creates a sense of communication with the audience—and, of course, communication between users in the community. This is something that I enjoy seeing unfold with our games, and that has continued to influence my work."

It's unusual for such a figure to be company director: the demands of running a business can easily smother creative endeavor. But Miyazaki sees himself as an outsider in the managerial class; he observes fellow-C.E.O.s like an anthropologist, joking that he sometimes uses them as inspiration for his monsters. He's also a nurturing boss—his team routinely calls him for personal advice—and is acutely aware of the hazards of the empowered auteur. "The thing I prize is total openness from the staff; I try to be frank about my own mistakes," he said. "Because of my influence over these games, people are often reluctant to give their honest opinion, even when it may matter most. So I try not to let pride get involved, and try to create trust."

I'd often wondered whether Miyazaki had a similar response, using games as a way of exerting control. "I enjoy the process of solving problems that I know can be fixed," he told me. "Impossible challenges? That's where I draw the line, and where I feel stressed out. So I'm extremely fortunate to be able to apply that process by creating games."

When I asked whether his family had played his games, he laughed and pointed out that his daughter was three. "Not quite old enough," he said. But there was another reason: Miyazaki worried that his work, behind its abstractions, contained something too personal to reveal. Total control, it seems, risked total exposure. "I don't want to let my family play my games, because I feel like they'd see a bad part of me, something that's almost unsavory," he said. "I don't know. I'd feel embarrassed. So I say: no Dark Souls in the house."