Scientists have unveiled a new species of raptor dinosaur discovered in southern Utah that sheds new light on several long-standing questions in paleontology, including how dinosaurs evolved on the lost continent of Laramidia (western North America) during the Late Cretaceousa period known as the zenith of dinosaur diversity.

The findings, which will be published in the journal PLoS ONE, also include fresh insight into the function of the highly recurved claw on the foot of raptor dinosaurs, made famous in the movie franchise Jurassic Park.

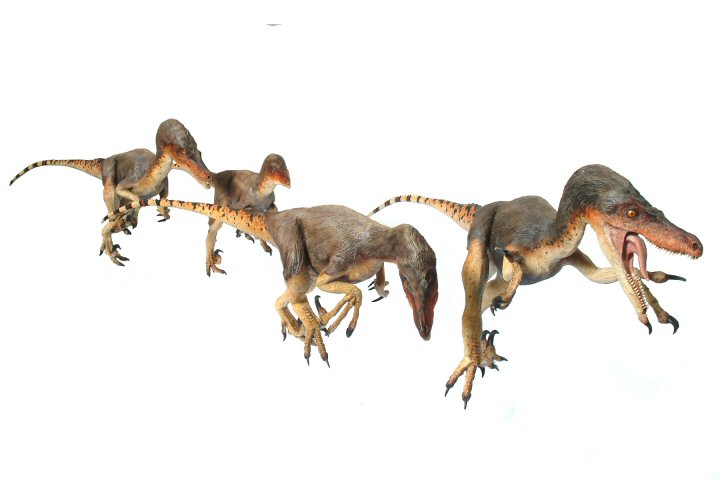

The new dinosaurdubbed Talos sampsoniis a member of a rare group of feathered, bird-like theropod dinosaurs whose evolution in North America has been a longstanding source of scientific debate, largely for lack of decent fossil material. Indeed, Talos represents the first definitive troodontid theropod to be named from the Late Cretaceous of North America in over 75 years.

Lindsay Zanno, lead author of the study naming the new dinosaur explained: Finding a decent specimen of this type of dinosaur in North America is like a lighting strike its a random event of thrilling proportions

When the team first began studying the Talos specimen, they noticed some unusual features on the second digit of the left foot, but initially assumed they were related to the fact that it belonged to a new species.

Zanno, an assistant professor of anatomy at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside and a research associate at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in Illinois, commented: When we realized we had evidence of an injury, the excitement was palpable. An injured specimen has a story to tell.

Thats because evidence of injury relates to function. The manner in which an animal is hurt can tell you something about what it was doing during life. An injury to the foot of a raptor dinosaur, for example, provides new evidence about the potential function of that toe and claw, she said.

In order to learn about the injury to the animals foot, the team scanned the individual bones using a high-resolution Computed Tomography (CT) scanner, similar to those used by physicians to examine bones and other organs inside the human body.

Although we could see damage on the exterior of the bone, our microCT approach was essential for characterizing the extent of the injury, and importantly, for allowing us to better constrain how long it had been between the time of injury and the time that this particular animal died, noted Patrick OConnor, associate professor of anatomy at Ohio University.

After additional CT scanning of other parts of the foot, the team realized that the injury was restricted to the toe with the enlarged claw, and the rest of the foot was not impacted.

More detailed study suggested that the injured toe was either bitten or fractured and then suffered from a localized infection.

People have speculated that the talon on the foot of raptor dinosaurs was used to capture prey, fight with other members of the same species, or defend the animal against attack.

Our interpretation supports the idea that these animals regularly put this toe in harms way, says Zanno.

Perhaps even more interesting is the fact that the injured toe exhibits evidence of bone remodelling thought to have taken place over a period of many weeks to months, suggesting that Talos lived with a serious injury to the foot for quite a long time.

It is clear from the bone remodelling that this animal lived for quite some time after the initial injury and subsequent infection, and that whatever it typically did with the enlarged talon on the left foot, whether that be acquire prey or interact with other members of the species, it must have been capable of doing so fairly well with the one on the right foot, added OConnor.

Trackways made by animals closely related to Talos suggest that they held the enlarged talon off the ground when walking. Our data support the idea that the talon of raptor dinosaurs was not used for purposes as mundane as walking, Zanno commented. It was an instrument meant for inflicting damage.

Talos sampsoni is the newest member of a growing list of new dinosaur species that have been discovered in Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument (GSENM) in southern Utah. Former President Clinton founded the monument in 1996, in part to protect the world class paleontological resources entombed within its 1.9 million acres of unexplored territory.

Zanno, along with colleague Scott Sampson, named the first dinosaur from the monumentHagryphus giganteusin 2005. Hagryphus (widely touted in the press as the turkey dinosaur) is also a theropod dinosaur, but one that belongs to a different subgroup known as oviraptorosaurs (or egg thief reptiles). Other GSENM dinosaurs include five new horned dinosaurs including the recently described and bizarrely ornate Kosmoceratops and Utahceratops, three new duck-bill dinosaurs including the toothy Gryposaurus monumentensis, two new tyrannosaurs, as well as undescribed ankylosaurs (armored dinosaurs), marine reptiles, giant crocodyliforms, turtles, plants, and a host of other organisms.

Other members of the research team include Mike Knell (a graduate student at Montana State University) who discovered the new specimen in 2008 in the Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (GSENM), southern Utah; Bureau of Land Management (BLM) paleontologist Alan Titus, leader of a decade-long paleontology reconnaissance effort in the monument; and David Varricchio, Associate Professor of Paleontology, Montana State University.

The bones of Talos sampsoni will be on exhibit for the first time in the Past Worlds Observatory at the new Utah Museum of Natural History, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Story Here