AuthenticM

Member

Enormous article detailing the potential effects of climate change from NYMag. I took some of the meatier parts, but there is much more at the link. I urge everyone to read the whole thing. At the very least, click on the link and scroll through the whole thing to give the site money through advertising.

I. Doomsday

II. Heat Death

III. The End of Food

IV. Climate Plagues

V. Unbreathable Air

VI. The Perpetual War

VII. Permanent Economic Collapse

VIII. Poisoned Oceans

IX. The Great Filter

-------

UPDATE 2017-07-19

The New York Magazine published an annotated edition of the article detailing the science, which you can read here.

David Roberts wrote an article on Vox defending the piece. He explains how the article is mostly right, and we shouldn't dismiss it as "doomsday nonsense". Excerpts:

I. Doomsday

It is, I promise, worse than you think. If your anxiety about global warming is dominated by fears of sea-level rise, you are barely scratching the surface of what terrors are possible, even within the lifetime of a teenager today. And yet the swelling seas and the cities they will drown have so dominated the picture of global warming, and so overwhelmed our capacity for climate panic, that they have occluded our perception of other threats, many much closer at hand. Rising oceans are bad, in fact very bad; but fleeing the coastline will not be enough.

Indeed, absent a significant adjustment to how billions of humans conduct their lives, parts of the Earth will likely become close to uninhabitable, and other parts horrifically inhospitable, as soon as the end of this century.

In between scientific reticence and science fiction is science itself. This article is the result of dozens of interviews and exchanges with climatologists and researchers in related fields and reflects hundreds of scientific papers on the subject of climate change. What follows is not a series of predictions of what will happen that will be determined in large part by the much-less-certain science of human response. Instead, it is a portrait of our best understanding of where the planet is heading absent aggressive action. It is unlikely that all of these warming scenarios will be fully realized, largely because the devastation along the way will shake our complacency. But those scenarios, and not the present climate, are the baseline. In fact, they are our schedule.

The Earth has experienced five mass extinctions before the one we are living through now, each so complete a slate-wiping of the evolutionary record it functioned as a resetting of the planetary clock, and many climate scientists will tell you they are the best analog for the ecological future we are diving headlong into. Unless you are a teenager, you probably read in your high-school textbooks that these extinctions were the result of asteroids. In fact, all but the one that killed the dinosaurs were caused by climate change produced by greenhouse gas. The most notorious was 252 million years ago; it began when carbon warmed the planet by five degrees, accelerated when that warming triggered the release of methane in the Arctic, and ended with 97 percent of all life on Earth dead. We are currently adding carbon to the atmosphere at a considerably faster rate; by most estimates, at least ten times faster. The rate is accelerating. This is what Stephen Hawking had in mind when he said, this spring, that the species needs to colonize other planets in the next century to survive, and what drove Elon Musk, last month, to unveil his plans to build a Mars habitat in 40 to 100 years. These are nonspecialists, of course, and probably as inclined to irrational panic as you or I. But the many sober-minded scientists I interviewed over the past several months the most credentialed and tenured in the field, few of them inclined to alarmism and many advisers to the IPCC who nevertheless criticize its conservatism have quietly reached an apocalyptic conclusion, too: No plausible program of emissions reductions alone can prevent climate disaster.

II. Heat Death

Since 1980, the planet has experienced a 50-fold increase in the number of places experiencing dangerous or extreme heat; a bigger increase is to come. The five warmest summers in Europe since 1500 have all occurred since 2002, and soon, the IPCC warns, simply being outdoors that time of year will be unhealthy for much of the globe. Even if we meet the Paris goals of two degrees warming, cities like Karachi and Kolkata will become close to uninhabitable, annually encountering deadly heat waves like those that crippled them in 2015. At four degrees, the deadly European heat wave of 2003, which killed as many as 2,000 people a day, will be a normal summer. At six, according to an assessment focused only on effects within the U.S. from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, summer labor of any kind would become impossible in the lower Mississippi Valley, and everybody in the country east of the Rockies would be under more heat stress than anyone, anywhere, in the world today.

III. The End of Food

Climates differ and plants vary, but the basic rule for staple cereal crops grown at optimal temperature is that for every degree of warming, yields decline by 10 percent. Some estimates run as high as 15 or even 17 percent. Which means that if the planet is five degrees warmer at the end of the century, we may have as many as 50 percent more people to feed and 50 percent less grain to give them. And proteins are worse: It takes 16 calories of grain to produce just a single calorie of hamburger meat, butchered from a cow that spent its life polluting the climate with methane farts.

Drought might be an even bigger problem than heat, with some of the worlds most arable land turning quickly to desert. Precipitation is notoriously hard to model, yet predictions for later this century are basically unanimous: unprecedented droughts nearly everywhere food is today produced. By 2080, without dramatic reductions in emissions, southern Europe will be in permanent extreme drought, much worse than the American dust bowl ever was. The same will be true in Iraq and Syria and much of the rest of the Middle East; some of the most densely populated parts of Australia, Africa, and South America; and the breadbasket regions of China. None of these places, which today supply much of the worlds food, will be reliable sources of any. As for the original dust bowl: The droughts in the American plains and Southwest would not just be worse than in the 1930s, a 2015 NASA study predicted, but worse than any droughts in a thousand years and that includes those that struck between 1100 and 1300, which dried up all the rivers East of the Sierra Nevada mountains and may have been responsible for the death of the Anasazi civilization.

IV. Climate Plagues

There are now, trapped in Arctic ice, diseases that have not circulated in the air for millions of years in some cases, since before humans were around to encounter them. Which means our immune systems would have no idea how to fight back when those prehistoric plagues emerge from the ice.

The Arctic also stores terrifying bugs from more recent times. In Alaska, already, researchers have discovered remnants of the 1918 flu that infected as many as 500 million and killed as many as 100 million about 5 percent of the worlds population and almost six times as many as had died in the world war for which the pandemic served as a kind of gruesome capstone. As the BBC reported in May, scientists suspect smallpox and the bubonic plague are trapped in Siberian ice, too an abridged history of devastating human sickness, left out like egg salad in the Arctic sun.

What concerns epidemiologists more than ancient diseases are existing scourges relocated, rewired, or even re-evolved by warming. The first effect is geographical. Before the early-modern period, when adventuring sailboats accelerated the mixing of peoples and their bugs, human provinciality was a guard against pandemic. Today, even with globalization and the enormous intermingling of human populations, our ecosystems are mostly stable, and this functions as another limit, but global warming will scramble those ecosystems and help disease trespass those limits as surely as Cortés did. You dont worry much about dengue or malaria if you are living in Maine or France. But as the tropics creep northward and mosquitoes migrate with them, you will. You didnt much worry about Zika a couple of years ago, either.

As it happens, Zika may also be a good model of the second worrying effect disease mutation. One reason you hadnt heard about Zika until recently is that it had been trapped in Uganda; another is that it did not, until recently, appear to cause birth defects. Scientists still dont entirely understand what happened, or what they missed. But there are things we do know for sure about how climate affects some diseases: Malaria, for instance, thrives in hotter regions not just because the mosquitoes that carry it do, too, but because for every degree increase in temperature, the parasite reproduces ten times faster. Which is one reason that the World Bank estimates that by 2050, 5.2 billion people will be reckoning with it.

V. Unbreathable Air

Our lungs need oxygen, but that is only a fraction of what we breathe. The fraction of carbon dioxide is growing: It just crossed 400 parts per million, and high-end estimates extrapolating from current trends suggest it will hit 1,000 ppm by 2100. At that concentration, compared to the air we breathe now, human cognitive ability declines by 21 percent.

Other stuff in the hotter air is even scarier, with small increases in pollution capable of shortening life spans by ten years. The warmer the planet gets, the more ozone forms, and by mid-century, Americans will likely suffer a 70 percent increase in unhealthy ozone smog, the National Center for Atmospheric Research has projected. By 2090, as many as 2 billion people globally will be breathing air above the WHO safe level; one paper last month showed that, among other effects, a pregnant mothers exposure to ozone raises the childs risk of autism (as much as tenfold, combined with other environmental factors). Which does make you think again about the autism epidemic in West Hollywood.

Then there are the more familiar forms of pollution. In 2013, melting Arctic ice remodeled Asian weather patterns, depriving industrial China of the natural ventilation systems it had come to depend on, which blanketed much of the countrys north in an unbreathable smog. Literally unbreathable. A metric called the Air Quality Index categorizes the risks and tops out at the 301-to-500 range, warning of serious aggravation of heart or lung disease and premature mortality in persons with cardiopulmonary disease and the elderly and, for all others, serious risk of respiratory effects; at that level, everyone should avoid all outdoor exertion. The Chinese airpocalypse of 2013 peaked at what would have been an Air Quality Index of over 800. That year, smog was responsible for a third of all deaths in the country.

VI. The Perpetual War

Climatologists are very careful when talking about Syria. They want you to know that while climate change did produce a drought that contributed to civil war, it is not exactly fair to saythat the conflict is the result of warming; next door, for instance, Lebanon suffered the same crop failures. But researchers like Marshall Burke and Solomon Hsiang have managed to quantify some of the non-obvious relationships between temperature and violence: For every half-degree of warming, they say, societies will see between a 10 and 20 percent increase in the likelihood of armed conflict. In climate science, nothing is simple, but the arithmetic is harrowing: A planet five degrees warmer would have at least half again as many wars as we do today. Overall, social conflict could more than double this century.

What accounts for the relationship between climate and conflict? Some of it comes down to agriculture and economics; a lot has to do with forced migration, already at a record high, with at least 65 million displaced people wandering the planet right now. But there is also the simple fact of individual irritability. Heat increases municipal crime rates, and swearing on social media, and the likelihood that a major-league pitcher, coming to the mound after his teammate has been hit by a pitch, will hit an opposing batter in retaliation. And the arrival of air-conditioning in the developed world, in the middle of the past century, did little to solve the problem of the summer crime wave.

VII. Permanent Economic Collapse

The most exciting research on the economics of warming has also come from Hsiang and his colleagues, who are not historians of fossil capitalism but who offer some very bleak analysis of their own: Every degree Celsius of warming costs, on average, 1.2 percent of GDP (an enormous number, considering we count growth in the low single digits as strong). This is the sterling work in the field, and their median projection is for a 23 percent loss in per capita earning globally by the end of this century (resulting from changes in agriculture, crime, storms, energy, mortality, and labor).

Tracing the shape of the probability curve is even scarier: There is a 12 percent chance that climate change will reduce global output by more than 50 percent by 2100, they say, and a 51 percent chance that it lowers per capita GDP by 20 percent or more by then, unless emissions decline. By comparison, the Great Recession lowered global GDP by about 6 percent, in a onetime shock; Hsiang and his colleagues estimate a one-in-eight chance of an ongoing and irreversible effect by the end of the century that is eight times worse.

The scale of that economic devastation is hard to comprehend, but you can start by imagining what the world would look like today with an economy half as big, which would produce only half as much value, generating only half as much to offer the workers of the world. It makes the grounding of flights out of heat-stricken Phoenix last month seem like pathetically small economic potatoes. And, among other things, it makes the idea of postponing government action on reducing emissions and relying solely on growth and technology to solve the problem an absurd business calculation. Every round-trip ticket on flights from New York to London, keep in mind, costs the Arctic three more square meters of ice.

VIII. Poisoned Oceans

That isnt all that ocean acidification can do. Carbon absorption can initiate a feedback loop in which underoxygenated waters breed different kinds of microbes that turn the water still more anoxic, first in deep ocean dead zones, then gradually up toward the surface. There, the small fish die out, unable to breathe, which means oxygen-eating bacteria thrive, and the feedback loop doubles back. This process, in which dead zones grow like cancers, choking off marine life and wiping out fisheries, is already quite advanced in parts of the Gulf of Mexico and just off Namibia, where hydrogen sulfide is bubbling out of the sea along a thousand-mile stretch of land known as the Skeleton Coast. The name originally referred to the detritus of the whaling industry, but today its more apt than ever. Hydrogen sulfide is so toxic that evolution has trained us to recognize the tiniest, safest traces of it, which is why our noses are so exquisitely skilled at registering flatulence. Hydrogen sulfide is also the thing that finally did us in that time 97 percent of all life on Earth died, once all the feedback loops had been triggered and the circulating jet streams of a warmed ocean ground to a halt its the planets preferred gas for a natural holocaust. Gradually, the oceans dead zones spread, killing off marine species that had dominated the oceans for hundreds of millions of years, and the gas the inert waters gave off into the atmosphere poisoned everything on land. Plants, too. It was millions of years before the oceans recovered.

IX. The Great Filter

So why cant we see it? In his recent book-length essay The Great Derangement, the Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh wonders why global warming and natural disaster havent become major subjects of contemporary fiction why we dont seem able to imagine climate catastrophe, and why we havent yet had a spate of novels in the genre he basically imagines into half-existence and names the environmental uncanny. Consider, for example, the stories that congeal around questions like, Where were you when the Berlin Wall fell? or Where were you on 9/11?  he writes. Will it ever be possible to ask, in the same vein, Where were you at 400 ppm? or Where were you when the Larsen B ice shelf broke up?  His answer: Probably not, because the dilemmas and dramas of climate change are simply incompatible with the kinds of stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, especially in novels, which tend to emphasize the journey of an individual conscience rather than the poisonous miasma of social fate.

Jim Hansen is another member of this godfather generation. Born in 1941, he became a climatologist at the University of Iowa, developed the groundbreaking Zero Model for projecting climate change, and later became the head of climate research at NASA, only to leave under pressure when, while still a federal employee, he filed a lawsuit against the federal government charging inaction on warming (along the way he got arrested a few times for protesting, too). The lawsuit, which is brought by a collective called Our Childrens Trust and is often described as kids versus climate change, is built on an appeal to the equal-protection clause, namely, that in failing to take action on warming, the government is violating it by imposing massive costs on future generations; it is scheduled to be heard this winter in Oregon district court. Hansen has recently given up on solving the climate problem with a carbon tax, which had been his preferred approach, and has set about calculating the total cost of extracting carbon from the atmosphere instead.

Hansen began his career studying Venus, which was once a very Earth-like planet with plenty of life-supporting water before runaway climate change rapidly transformed it into an arid and uninhabitable sphere enveloped in an unbreathable gas; he switched to studying our planet by 30, wondering why he should be squinting across the solar system to explore rapid environmental change when he could see it all around him on the planet he was standing on. When we wrote our first paper on this, in 1981, he told me, I remember saying to one of my co-authors, This is going to be very interesting. Sometime during our careers, were going to see these things beginning to happen.

Several of the scientists I spoke with proposed global warming as the solution to Fermis famous paradox, which asks, If the universe is so big, then why havent we encountered any other intelligent life in it? The answer, they suggested, is that the natural life span of a civilization may be only several thousand years, and the life span of an industrial civilization perhaps only several hundred. In a universe that is many billions of years old, with star systems separated as much by time as by space, civilizations might emerge and develop and burn themselves up simply too fast to ever find one another. Peter Ward, a charismatic paleontologist among those responsible for discovering that the planets mass extinctions were caused by greenhouse gas, calls this the Great Filter: Civilizations rise, but theres an environmental filter that causes them to die off again and disappear fairly quickly, he told me. If you look at planet Earth, the filtering weve had in the past has been in these mass extinctions. The mass extinction we are now living through has only just begun; so much more dying is coming.

And yet, improbably, Ward is an optimist. So are Broecker and Hansen and many of the other scientists I spoke to. We have not developed much of a religion of meaning around climate change that might comfort us, or give us purpose, in the face of possible annihilation. But climate scientists have a strange kind of faith: We will find a way to forestall radical warming, they say, because we must.

-------

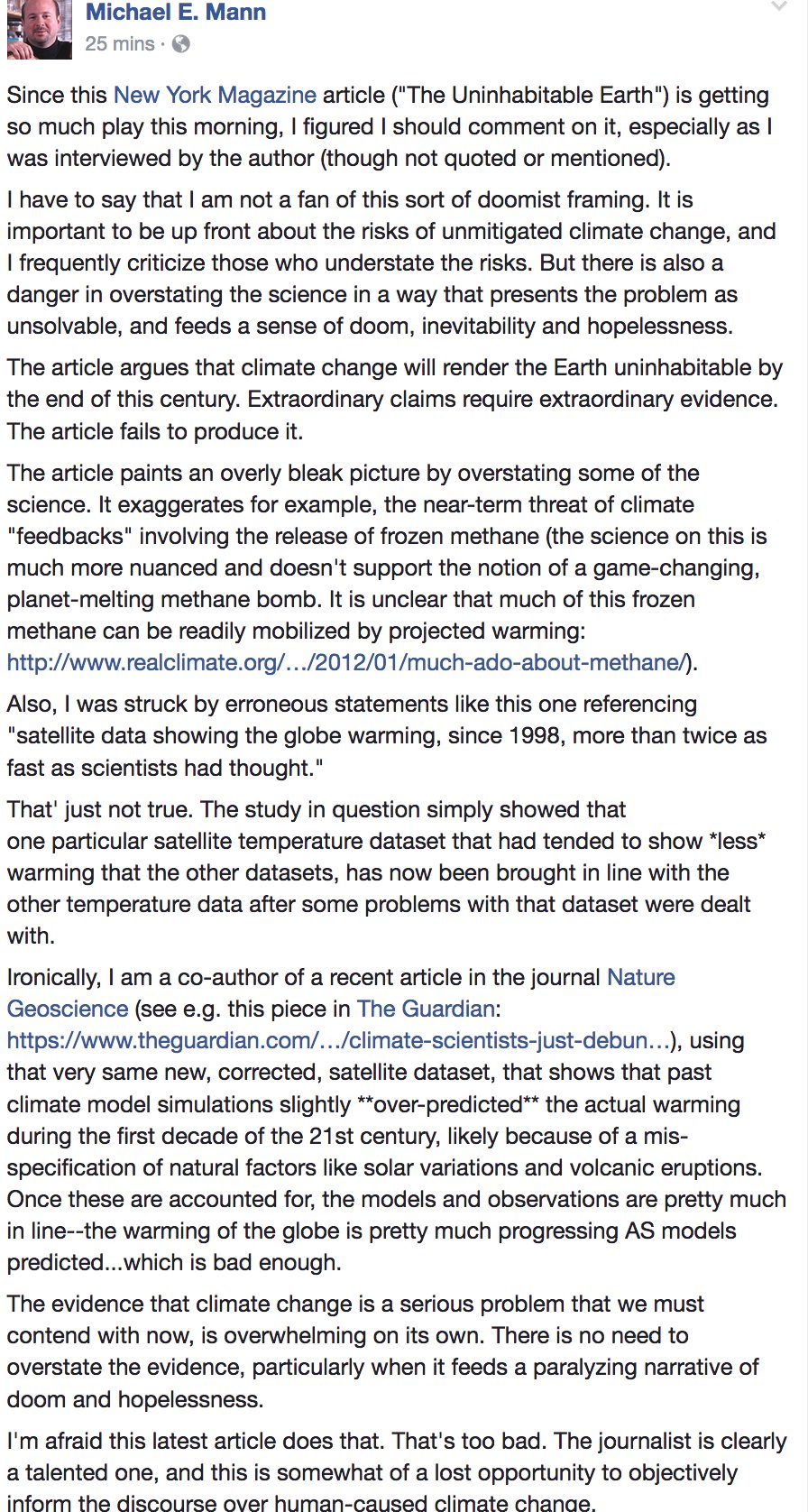

UPDATE 2017-07-19

The New York Magazine published an annotated edition of the article detailing the science, which you can read here.

David Roberts wrote an article on Vox defending the piece. He explains how the article is mostly right, and we shouldn't dismiss it as "doomsday nonsense". Excerpts:

It is true that the world is making progress on carbon emissions. Many pieces have been written about that and Im sure many more will be. But Wallace-Wells piece was not about that. It was about what will happen if we keep on as-is.

As many people have noted, we probably wont keep on as-is, which makes the worst-case unlikely. But Wallace-Wells is not predicting it will happen. What follows is not a series of predictions of what will happen, he writes early on. That will be determined in large part by the much-less-certain science of human response.

Hes merely describing what could happen if we cease to act, which no one wants ... except one of the two major political parties in the worlds most powerful country, including the man in charge of the executive branch and military.

Lest the message be lost, Freemans piece was originally headlined: Do not accept New York Mag's climate change doomsday scenario.

Got that? Do not accept it. Do not feel sad. Be hopeful and positive. Failure to be properly hopeful and positive will be punished!

The theme of all these critiques is that bad, scary news doesnt help. It terrifies and paralyzes people.

People often cite social science in support of this critique (Emily Atkin at the New Republic has a few references), but I think the lesson, such as it is, has been wildly overlearned.

First, social scientists are forever testing how individuals respond to various messages in lab conditions, in the short-term, but the dynamics that matter most on climate are social and long-term. It may be that there are social dynamics that require some fear and paralysis before a collective breakthrough. At the very least, it seems excessive to draw a pat fear never works conclusion from these sorts of data.

Second, even if its true that fear only works when it is joined with a sense of agency and efficacy, that doesnt mean that every single instance of fear has to be accompanied by a serving of hope. Not every article has to be about everything. In fact, if you ask me, the [two paragraphs of fear], BUT [12 paragraphs of happy news] format has gotten to be a predictable snooze. Some pieces can just be about the terrible risks we face. Thats okay.

Its fine for activists to be congenitally positive thats their job. But Im with Slates Susan Matthews: its just weird for journalists and analysts to worry about overly alarming people regarding the biggest, scariest problem humanity has ever faced. By any sane accounting, the ranks the under-alarmed outnumber the over-alarmed by many multiples. The vast majority of people do not have an accurate understanding of how bad climate change has already gotten or how bad it is likely to get, much less how bad it could get if we keep electing crazy people.

When there are important things that people dont understand, journalists should explain those things. Attempts at dime-store social psychology are unlikely to lead to better journalism.