Source: https://www.wsj.com/articles/rural-america-is-the-new-inner-city-1495817008

I strongly recommend reading the entire piece- there are charts and graphs that are baked into the article that I can't copy/paste easily where I'm at, and there are a lot of anecdotes I've left out that are woven into the piece- I've just pulled the hard data into the OP.

One thing this article illustrates very well is that the forces leading to this decline aren't reversible. This isn't something where job retraining alone will help, because by and large, the jobs aren't going to be coming back because they're moving permanently to bigger metropolitan areas. And with the US's fixation on homeownership, this leaves a very large number of people trapped, shackled to investments that are no longer going to pay out as expected.

I strongly recommend reading the entire piece- there are charts and graphs that are baked into the article that I can't copy/paste easily where I'm at, and there are a lot of anecdotes I've left out that are woven into the piece- I've just pulled the hard data into the OP.

One thing this article illustrates very well is that the forces leading to this decline aren't reversible. This isn't something where job retraining alone will help, because by and large, the jobs aren't going to be coming back because they're moving permanently to bigger metropolitan areas. And with the US's fixation on homeownership, this leaves a very large number of people trapped, shackled to investments that are no longer going to pay out as expected.

At the corner where East North Street meets North Cherry Street in the small Ohio town of Kenton, the Immaculate Conception Church keeps a handwritten record of major ceremonies. Over the last decade, according to these sacramental registries, the church has held twice as many funerals as baptisms.

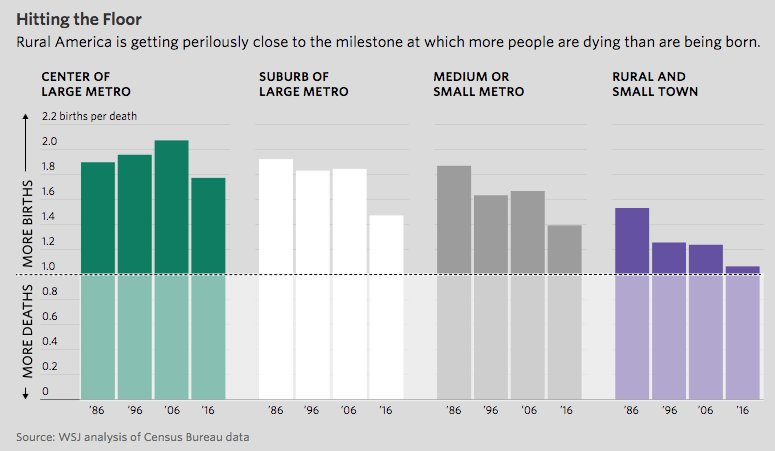

In tiny communities like Kenton, an unprecedented shift is under way. Federal and other data show that in 2013, in the majority of sparsely populated U.S. counties, more people died than were born—the first time that's happened since the dawn of universal birth registration in the 1930s.

For more than a century, rural towns sustained themselves, and often thrived, through a mix of agriculture and light manufacturing. Until recently, programs funded by counties and townships, combined with the charitable efforts of churches and community groups, provided a viable social safety net in lean times.

Starting in the 1980s, the nation's basket cases were its urban areas—where a toxic stew of crime, drugs and suburban flight conspired to make large cities the slowest-growing and most troubled places.

Today, however, a Wall Street Journal analysis shows that by many key measures of socioeconomic well-being, those charts have flipped. In terms of poverty, college attainment, teenage births, divorce, death rates from heart disease and cancer, reliance on federal disability insurance and male labor-force participation, rural counties now rank the worst among the four major U.S. population groupings (the others are big cities, suburbs and medium or small metro areas).

In fact, the total rural population—accounting for births, deaths and migration—has declined for five straight years.

In the 1980s, rural Americans faced fewer teen births and lower divorce rates than their urban counterparts. Now, their positions have flipped entirely. The education and employment gaps between rural and urban areas have widened as rural areas have aged much faster than the rest of the country. And even after adjusting for the aging population, rural areas have become markedly less healthy than America's cities. In 1980, they had lower rates of heart disease and cancer. By 2014, the opposite was true.

In the first half of the 20th century, America's cities grew into booming hubs for heavy manufacturing, expanding at a prodigious clip. By the 1960s, however, cheap land in the suburbs and generous highway and mortgage subsidies provided city dwellers with a ready escape—just as racial tensions prompted many white residents to leave.

Gutted neighborhoods and the loss of jobs and taxpayers contributed to a socioeconomic collapse. From the 1980s into the mid-1990s, the data show, America's big cities had the highest concentration of divorced people and the highest rates of teenage births and deaths from cardiovascular disease and cancer. "The whole narrative was ‘the urban crisis,'" said Henry Cisneros, who was Bill Clinton's secretary of housing and urban development.

To address these problems, the Clinton administration pursued aggressive new policies to target urban ills. Public-housing projects were demolished to break up pockets of concentrated poverty that had incubated crime and the crack cocaine epidemic.

At that time, rural America seemed stable by comparison—if not prosperous. Well into the mid-1990s, the nation's smallest counties were home to almost one-third of all net new business establishments, more than twice the share spawned in the largest counties, according to the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan public-policy organization. Employers offering private health insurance propped up medical centers that gave rural residents access to reliable care.

By the late 1990s, the shift to a knowledge-based economy began transforming cities into magnets for desirable high-wage jobs. For a new generation of workers raised in suburbs, or arriving from other countries, cities offered diversity and density that bolstered opportunities for work and play. Urban residents who owned their homes saw rapid price appreciation, while many low-wage earners were driven to city fringes.

As crime rates fell, urban developers sought to cater to a new upper-middle class. Hospital systems invested in sophisticated heart-attack and stroke-treatment protocols to make common medical problems less deadly. Campaigns to combat teenage pregnancy favored cities where they could reach more people.

As large cities and suburbs and midsize metros saw an upswing in key measures of quality of life, rural areas struggled to find ways to harness the changing economy.

There has long been a wage gap between workers in urban and rural areas, but the recession of 2007-09 caused it to widen. In densely populated labor markets (with more than one million workers), Prof. Moretti found that the average wage is now one-third higher than in less-populated places that have 250,000 or fewer workers—a difference 50% larger than it was in the 1970s.

As employers left small towns, many of the most ambitious young residents packed up and left, too. In 1980, the median age of people in small towns and big cities almost matched. Today, the median age in small towns is about 41 years—five years above the median in big cities. A third of adults in urban areas hold a college degree, almost twice the share in rural counties, census figures show.

Consolidation has shut down many rural hospitals, which have struggled from a shortage of patients with employer-sponsored insurance. At least 79 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.