In their rich and detailed conversation, Jeremiah Johnston and Alisa Childers examine the claim that the Shroud of Turin may be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus Christ. Johnston, initially skeptical due to its reputation as a "Catholic relic," describes how further investigation changed his mind. He outlines several compelling lines of evidence. First, modern science has been unable to reproduce or explain how the image of a crucified man was formed on the 14-foot linen cloth. Over 500,000 hours of scientific research across 63 disciplines—including work from Los Alamos, Sandia Labs, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory—have determined the image is not paint, dye, or burn marks. Instead, it is a superficial image on only the topmost fibers, not absorbed into the fabric. The bloodstains—proven to be real, human, male blood of Semitic type AB—precede the image, indicating that the body was wrapped in the cloth before the image formed. Further analysis found high levels of bilirubin and creatinine—signs of extreme trauma, organ failure, and cardiac stress consistent with crucifixion. The cloth also contains limestone dust consistent with Jerusalem's geology, likely from the victim falling while carrying a crossbeam, and more than 50 unique pollen spores indigenous to Jerusalem that bloom during spring—the season when Jesus was crucified.

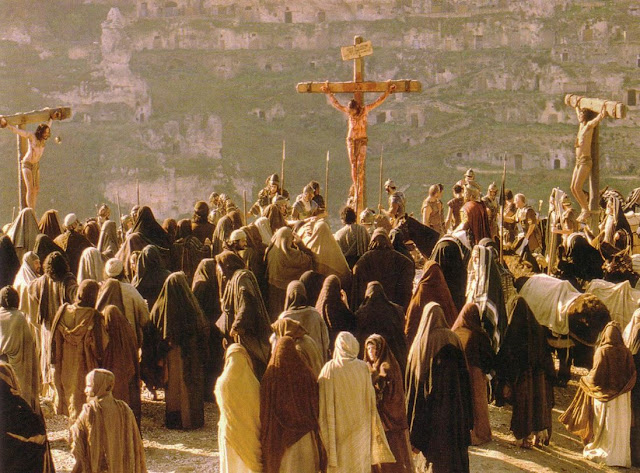

Johnston adds that the anatomical details of the image align exactly with Roman crucifixion practices: nail wounds at the wrists, no broken bones, signs of scourging, and postmortem blood flow from the side. The Shroud even shows separated shoulders, matching descriptions of carrying a heavy cross. He explains that the image appears as a photographic negative, which became clear only when photographed in 1898. This discovery sparked modern investigations, which concluded the image likely formed in a sudden burst of radiation-like energy—estimated at 40 trillion watts in 1/40th of a second. Probability analyses by scholars such as Ken Stevenson, Gary Habermas, and Bruno Barberis suggest there's only a 1 in 200 million chance the image could be of anyone other than Jesus of Nazareth. Johnston also references the cloth's historical journey under different names (like the "Image of Edessa" and the "Mandylion"), with pollen from those locations further validating its authenticity.

Alisa responds with respectful skepticism, not doubting the resurrection itself but wrestling with two theological concerns: First, she questions whether God would provide such clear-cut physical proof of Jesus' resurrection, noting that throughout history, God seems to invite faith through veiled, rather than overwhelming, evidence. Second, she expresses concern that widespread images of the Shroud (used in recreations and AI renderings) could lead to inaccurate visualizations of Jesus in prayer or worship, potentially distracting from the deeper spiritual truth of His sacrificial death. Johnston acknowledges these concerns, affirming that the shroud neither replaces Scripture nor serves as the sole foundation of faith. Rather, he sees it as archaeological and scientific evidence that harmonizes with the biblical account, not unlike discoveries confirming Pilate's existence or King David's historicity. He encourages curiosity over fear, and frames the Shroud as a tangible witness—one more layer of evidence pointing to the truth, depth, and historical reliability of the Gospel.