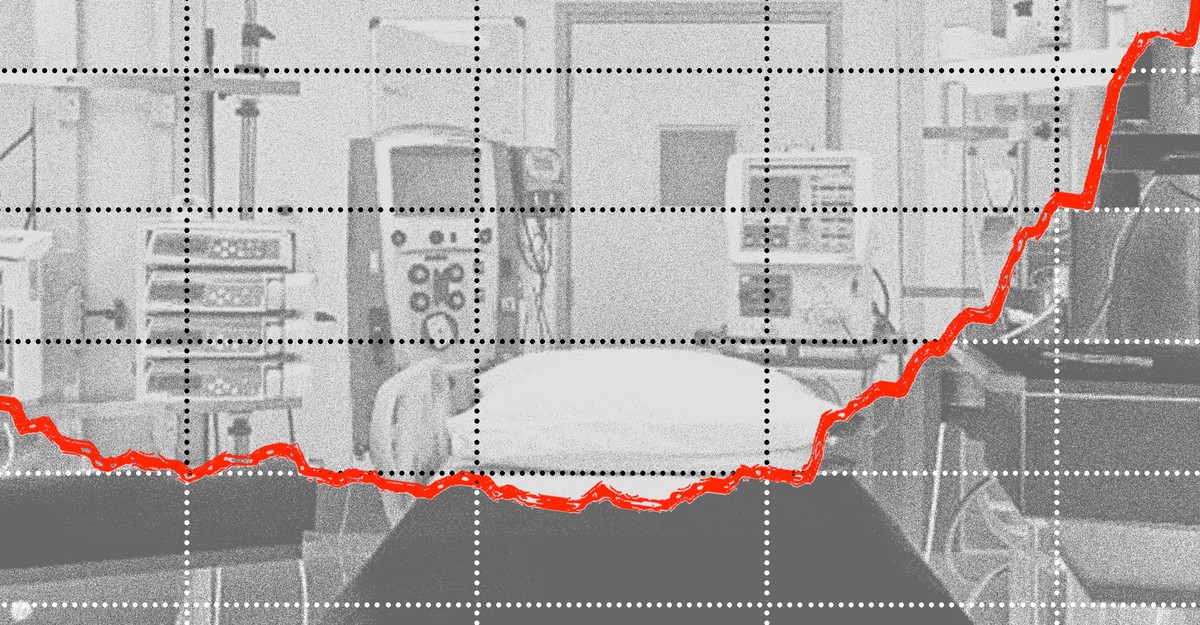

U.S. hospitals are struggling to get the workers they need to treat patients through the winter's COVID-19 surge as the virus collides with a historically tight labor market.

High demand for labor throughout the economy is making it harder to find replacements for doctors, nurses and support staff who have been sidelined by the omicron variant. It's especially tough in small towns and rural areas with aging populations and fewer people entering the workforce.

Finding sufficient staff is a daily challenge that industry veterans say is harder than any time they can remember. Job openings in health care and social assistance are more than double their pandemic lows, and a record number of people are quitting.

"This is the most significant labor shortage that we have ever seen," said Sally Zuel, vice president of human resources at Union Health in Terre Haute, Indiana.

As a result, wages are climbing skyward: In November hospitals' labor expense per patient was 26% above the pre-COVID level two years earlier, according to data from consulting firm Kaufman Hall.

The workforce squeeze is upending every aspect of care. A Fort Lauderdale, Florida, hospital temporarily closed its labor and delivery unit due to staff shortages. The chief executive of a 25-bed facility in rural Nebraska monitored patients on the floor himself Monday. In Indiana, where the National Guard was called in to reinforce hospital staff, administrators offer double pay to workers to extend their shifts when colleagues are sick.

"We've had more staff out because they've tested positive and have contracted COVID than we did at the very beginning," said Lynda Shrock, vice president of human resources at Logansport Memorial Hospital in Logansport, Indiana.

Long before the arrival of COVID, doctors and nurses were in high demand. The pandemic has only made that shortage worse as some health-care workers, depleted by two years fighting COVID, opt for early retirement.

Others are trading permanent positions for lucrative short-term travel assignments at premium pay, driving up labor costs. Three out of four health-care facilities were looking for temporary allied health professionals — a category that includes clinical workers who aren't doctors, nurses or advanced practitioners — according to a December survey by staffing company AMN Healthcare.

Beyond shortages of clinical professionals, it has become tougher to hire and retain workers in other roles essential to keeping medical centers running, from technicians to food service workers to the people who prep rooms in between patients, hospital officials say. To fill those positions, it's increasingly necessary to compete on wages with other industries even while persuading workers that they can safely prepare food or clean floors inside health-care buildings during a pandemic.

In Terre Haute, Indiana, Zuel scrambles to get adequate coverage for each 12-hour shift. The health system, with about 3,000 employees, recently decided to move nurses from support positions into direct patient care. Radiology and lab technicians, phlebotomists and respiratory therapists are all hard to find.

Some relief arrived in uniform in December: The state sent a couple of medics and other support staff from the National Guard. They mostly work in the emergency department, where every morning patients wait for hospital beds to open. Others work in nutrition.

The current COVID surge in the area isn't expected to subside before February. The volume of patients means staffing will remain tight. "We need every person every day," Zuel said.

In November, as COVID spread throughout the state, Indiana's unemployment rate was 3%, or 1.2 percentage points lower than national level. The tight labor market has had ripple effects: Sometimes short-staffed pharmacies close without notice, so patients can't pick up their prescriptions after they're discharged, hospital officials said.

Nebraska has the lowest unemployment rate of any U.S. state, at 1.8% in November. In that environment, lots of employers struggle to find workers. But the stakes in health care are higher, especially in the COVID era.

Troy Bruntz runs Community Hospital, a 25-bed critical access facility in McCook, Nebraska. He's been trying to recruit a third ultrasound technician for at least six months without getting a single application.

For lower-level positions, the hospital competes with the local Walmart store, where wages are rising. He monitors the pay offered by the retailer as well as the other large local employers, a hose manufacturer and an irrigation equipment supplier.

"What used to be an $8 job now is $15," said Bruntz, a 52-year-old who once worked as an accountant for KPMG. "That's the only way we get people to come to work."

Most of the patients in Community Hospital aren't there for COVID, but the facility is still full. Patient transfers get delayed as larger regional facilities fill up too, backing up the emergency room. "I went to the floor to help," Bruntz said. "I'm a CPA, remember – but I can sit and watch a patient that needs someone to monitor them. And I did."

He sees a long-term dilemma that will persist beyond COVID waves, particularly in rural areas with aging populations. "We're going to have so many more people retiring than entering the workforce that this is just going to get worse," Bruntz said.

Across the state in Columbus, Nebraska, Mike Hansen, chief executive of Columbus Community Hospital, said hourly entry-level wages have been going up for two years and are now in the $15 to $18 range. Nursing wages have increased by $4 to $6 per hour just in the last year, to start at $35 to $40 and rising with experience.

Revised quarantine guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have helped get staff back faster after exposures or illnesses, he said.

Still, the hospital is admitting six to 12 COVID patients daily. Other patients coming in seem to be sicker, Hansen said. He's hoping that the omicron variant may cause less severe disease, resulting in fewer patients needing hospitalization.

Hansen, 61, calls the pandemic labor squeeze the worst in his four-decade career. "People need to realize, health-care people have been at this for almost two years now," he said. "It's been highly stressful."

gothamist.com