The Panama Leaks case is about to reach its much-awaited crescendo.

And for the second time, over the past one hundred days, the entire nation is looking towards the honourable Supreme Court for accountability of the most influential family in Pakistan's politico-financial paradigm.

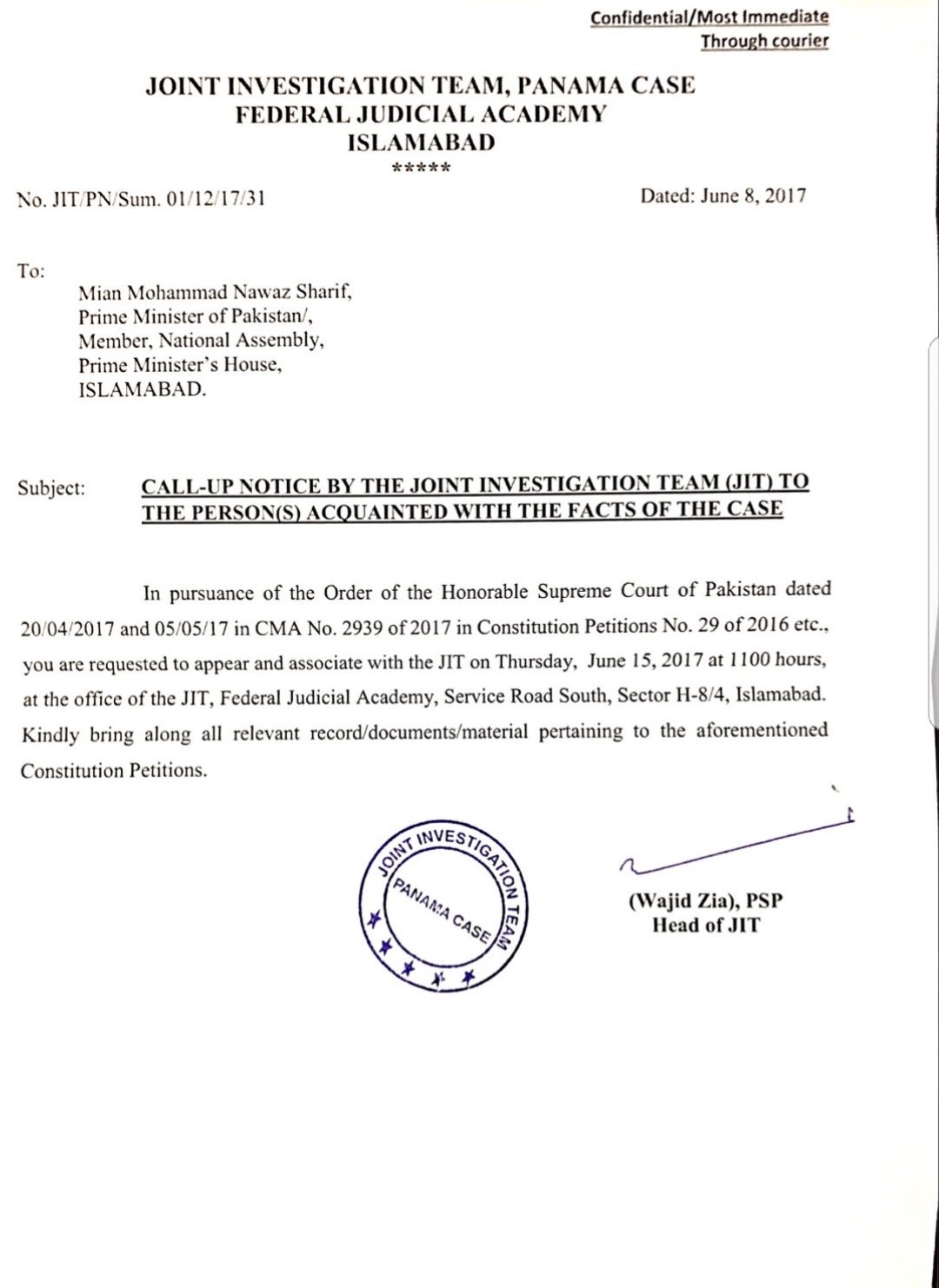

This case, in its narrowest sense, is about the disqualification of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

However, a deeper analysis of the issues involved (especially in regards to the ongoing drama concerning JIT proceedings) would reveal that this case is about much more than simply the disqualification of one individual.

It involves important (even existential) questions about the tenacity of our State, and its institutions, to hold the powerful and the mighty accountable for their private and public conduct.

This case is not simply about Neilsen Enterprises and Nescoll Limited; in equal measure, it is about the National Accountability Bureau and the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan.

It is not simply about Maryam Safdar and Hussain Nawaz; in equal measure, it is about Qamar Zaman and Zafar Hijazi.

Amidst all the chaos concerning JIT proceedings – including alleged threats to JIT members, leaked photograph, whatsapp calls, and SECP record tampering – an important constitutional question seems to have escaped our collective focus: will the final judgment be rendered by this three-member bench, or will it be referred back to the original five-member bench for a decision?

In this regard, if the case is to be (finally) decided by this honourable three-member bench, what will be the consequence of judgments authored by Justice Asif Saeed Khosa and Justice Gulzar Ahmed? Were they of no judicial or consequential value? Let us assume, for a moment, that this three-member bench decides the case in Mr.

Nawaz Sharif's favor with a 2:1 majority (one honourable member deciding against the Prime Minister), will it not be true (then) that, of the original five members, three have decided against the Sharif family? Should he not then be disqualified?

To this end, it is important to ask: did the five-member bench render its final "judgment" on the 20th of April? Or was "Order of the Court" not the same as its final judgment? Put it another way, did the "Order of the Court" dispose off the petitions in April? Is there anything in the judgment to indicate as such? Or did the court, instead, decide that it will render its final judgment after the JIT proceedings have been completed? Are the JIT proceeding, and the special three-member ‘implementation bench', merely an extension of the original proceedings? And if so, can this three-member bench render the final verdict? Or will the matter (necessarily) be referred back to original bench for its conclusive "judgment'?

These, and related questions, are of immense consequence for the Panama case.

Because if the final judgment, post-JIT report, is to be rendered by this three-member bench, then at least two honourable judges would have to decide against the Prime Minister for him to be disqualified.

On the other hand, in case the matter is to be referred back to the original five-member bench (two of whom have already decided against the Prime Minister), only more honourable judge can effectuate the Prime Minister's disqualification.

And, keeping in mind the stakes involved, the question as to whether the judgment is to be rendered by a five or a three-member bench, could well determine the course of governance and democracy for the foreseeable future in Pakistan.

Away from political consequences, in order to answer this critical question of bench formation, it is essential to once again parse through the order of the honourable court, dated 20th of April.

A careful reading of the 547 pages, authored by five honourable judges, would reveal that, in essence, there are only two ‘final' judgments in the field: one, authored by Justice Asif Khosa (which disqualifies the Prime Minister on merits) and the other by Justice Gulzar Ahmed (which fully agrees with Justice Khosa on the merits of the case, and adds an additional note on the "singular point" concerning the applicability and scope of Article 184(3)).

The other three honourable judges (forming the majority) did not render a ‘final' judgment.

Instead, they identified and observed the multi-faceted issues that require inquiry, before a final judgment can be announced.

In the words of Justice Ijaz-ul-Ahsan, "regrettably, most material questions have remained unanswered or answered insufficiently by [Prime Minister] and his children.

" As a result, the "Order of the Court", declares that there are numerous questions that "go to the heart of the matter and need to be answered", for which a JIT has been constituted.

The Order also directs the JIT to "submit its periodical reports every two weeks", and final report within sixty days, before a special bench (of three-members) constituted to "ensure implementation" of the Order.

And only after the final JIT report has been completed, under the auspices of the special implementation bench, will the court pass its definitive orders/directions.

In other words, having observed "patently contradictory statements" of the PM and his family, and that "no effort has been made to provide even the basic answers" (Justice Ahsan), the majority decided that "investigation appears to be necessary before we can proceed further in the matter" (Justice S.

Azmat Saeed).

To make matters clearer, Justice Azmat Saeed observes that, once the JIT furnishes its report, "this court will examine the matter of disqualification of [PM]".

This (five-member) court.

Not a sub-set of it.

And for this reason, the majority judges did not "dispose off" the case, as is customary whenever a final judgment has been rendered.

In light of the above, it is perhaps erroneous to assume that the "implementation" bench can pass a final judgment by itself, instead of the original (five-member) bench.

Unfortunately, there is no real precedent for this in the recent jurisprudence of our superior courts.

A comparison with the NRO case, in which an "implementation" bench had been constituted to oversee the carrying out of Court's directions, is also inaccurate.

Importantly, in the NRO judgment, no aspect of the case required further "investigation", before a judgment of the court could be rendered.

The judgment (of all concerned judges) was final and declarative.

It merely needed to be implemented.

In the Panama case, on the other hand, three of the five honourable judges of the bench have yet to render their final decision.

And even if one of the (undecided) judges holds the Prime Minister guilty, Justice Asif Khosa and Gulzar Ahmed will immediately find themselves in the majority.

These are challenges times for our polity, our State institutions, and the honourable Court.

Panama case has exposed the caustic nature of our politics (re: Nihal Hashmi), and the feeble state of our institutions (re: Qamar Zaman and Zafar Hjiazi).

The honourable Court, however, must stay clear of all such passions and prejudices.

As it has, so far.

Entering into the final stages of this politico-legal saga, it is important that we adhere to the constitutional requirements and procedures, which form the bedrock of our teetering democracy.

As such, the five-member bench, which heard the Panama case at length, must render the final judgment.

Whatever that judgment might be.

Because the last thing that we, as a people, can afford at this stage, is a controversy concerning why a (majority of?) three-member bench determined the fate of Panama case, and why the judgments rendered by Justice Khosa and Justice Gulzar were not counted towards the outcome.