The evening that Donald Trump fired FBI director James Comey, plunging Washington into chaos and possibly propelling the nation toward a constitutional crisis, the president's most persistent legal antagonist was flying high above America. On a cross-country JetBlue flight, Eric Schneiderman, the attorney general of New York State, was watching a seat-back TV when he learned the news the way almost everyone else — including Comey — did, with a shocking flash. "There was a group of lawyers on the plane who recognized me," Schneiderman said the next day. As the news spread through the cabin, he began to feel glances directed his way. The usual decorum fell away, and one passenger leaned over to Schneiderman. "I bet you can't wait for the plane to land," he said.

It wouldn't be fair to say that Schneiderman is enjoying this turbulent political ride we're on, but history has conspired to place him in a vital place on the ground. Since the election decapitated Democrats on the national level, putting Jeff Sessions in charge of the Department of Justice and leaving Republicans in control of congressional oversight, Schneiderman and other Democratic state attorneys general have led the legal resistance to Trump. Long before the Russians — or really anyone — dreamed of a President Trump, Schneiderman was investigating him, pursuing the allegedly fraudulent marketing of his for-profit university. And long before Trump was attacking federal judges, the leaky intelligence community, or law-enforcement officials with a reputation for stubborn probity, he was ridiculing New York's AG as a "lightweight." The idea that Schneiderman, a compact, tightly wound Upper West Side liberal whose office is accustomed to pursuing consumer scams or busting upstate heroin rings (as he did last week), might be a last line of defense for what he calls "bedrock principles of the United States" — it's frankly a little preposterous. But the framers of our Constitution designed our system to have hidden pockets of resiliency, and the power of the states is one of them.

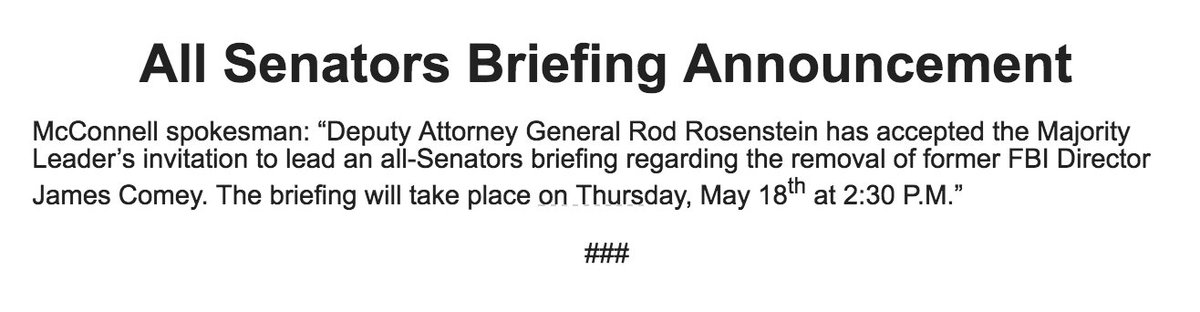

"For those of us who are protectors of the rule of law, the state attorneys general," Schneiderman said, "we have a role to play, to make sure that the system survives." When his plane landed, Schneiderman started contacting his colleagues in other states, as well as Democrats in Washington, coordinating an emergency response. On May 11, he joined a group of 20 attorneys general in signing a letter to Rod Rosenstein, the Justice Department official overseeing the Russia investigation, calling for the appointment of a special counsel.

Even before Comey's firing, some well-placed congressional Democrats had been urging Schneiderman to probe the Trump campaign's suspected Kremlin connection, as far afield as that might seem for a state officeholder. But New York, of course, is home to the Trump Organization and its bank accounts. "We have jurisdiction over everything because we're New York, and every check clears New York," said former state attorney general (and governor) Eliot Spitzer, whose high-profile prosecutions on Wall Street demonstrated the office's national reach. "There are odd jurisdictional hooks that sometimes come into play. Money laundering may be implicated here."

Schneiderman, however, said he is hoping that Comey's firing will spur Republicans to back a bipartisan probe. "It is tremendously important that the FBI not be run as a political operation," he said. "And it's very important to Americans on both sides of the aisle." He said he talked with contacts who were with the FBI director in L.A. when he was canned who told him they were outraged by the "sense of total disrespect" conveyed by the abrupt move, with its strong-arm theatrics, like the firing letter delivered by Trump's loyal bodyguard. "It's not the way you treat the director of the FBI," Schneiderman said, "whatever your disagreements with him may be."

Like many Democrats, Schneiderman had contradictory feelings about Comey. He had relied on the FBI as a partner in investigations and had hoped its director's reputation for independence would provide a solid check on Trump. At the same time, he was highly critical of Comey's actions during the Hillary Clinton email investigation. Schneiderman campaigned for Clinton, and on Election Night, he absorbed the news of her defeat — which many attributed to Comey — at her party at the Javits Center. The next morning, he presided over an emotional meeting at the attorney general's offices in lower Manhattan at which he told his staff to rally and to begin thinking about how to play a rearguard role.

"When Trump was elected, it became very clear to me, having known him for some time, that there were going to be new challenges," Schneiderman told me in April in an interview at his Broadway office, which looks out on the harbor and the World Trade Center memorial — a reminder of the stakes of law enforcement in New York. "This is a president who doesn't like to see checks on his power," he said, and a Congress with "a real reluctance to serve as a check on the Executive branch."

Before there was ‘Lyin' Ted' and ‘Little Marco,' there was ‘Clockwork Eric.'

"The states are able to serve as a backup," he said. Particularly New York, whose attorney general's office is perhaps the most powerful in the country, aided by the Martin Act, a state law that gives sweeping powers to investigate financial fraud. Past occupants of the office have used that power to raise their political profiles — both of Schneiderman's immediate predecessors, Spitzer and Andrew Cuomo, ended up as governor. It's no secret that Schneiderman would like to follow that example, and his confrontational stance toward Trump has made him a popular figure on the left. But it could also be an effective litigation strategy. Schneiderman and other state attorneys general led the successful counterattack against Trump's initial Muslim-nation immigration ban, and similar lawsuits could slow the administration's moves on civil rights and environmental regulations. "I think that we're in a situation now," Schneiderman said, "where the confrontations provoked very early on have set up an unprecedented set of battle lines."

Firing Comey opened up a new front. Beyond the implications for the Russia investigation, Trump's actions have sent a very public message to the law-enforcement bureaucracy about the president's tolerance for questioning. Schneiderman has experienced his vindictive streak firsthand, during his investigations of Trump University and, last year, of the Trump Foundation's fund-raising practices. Trump filed an ethics complaint against him (it was dismissed) and set up a website to attack him. The New York Observer — Jared Kushner's newspaper — published a memorably savage hit piece. "The front page of the Observer was my picture as the Malcolm McDowell character in A Clockwork Orange," he recalled. "So before there was ‘Lyin' Ted' and ‘Little Marco,' there was ‘Clockwork Eric.' I've seen the scorched-earth approach for years."

Trump vowed never to settle the Trump University case. He did, right after the election, for $25 million. It may prove to be a template for future legal dramas. Trump may have the power to squelch federal investigators, but Schneiderman's office has a staff of some 650 attorneys and formidable resources. In what was widely viewed as a preparatory move for cases to come, he recently hired a public-corruption prosecutor who worked for Preet Bharara, the U.S. Attorney for New York controversially ousted by Trump. (The Trump Foundation investigation, for one, is ongoing.)

"If it's hard to get checks on the presidency from Congress, we're going to try to fill that space," Schneiderman said. "I'm willing to bet on the rule of law. I think at the end of the day, it's what people want. I will bet on that to survive this presidency."