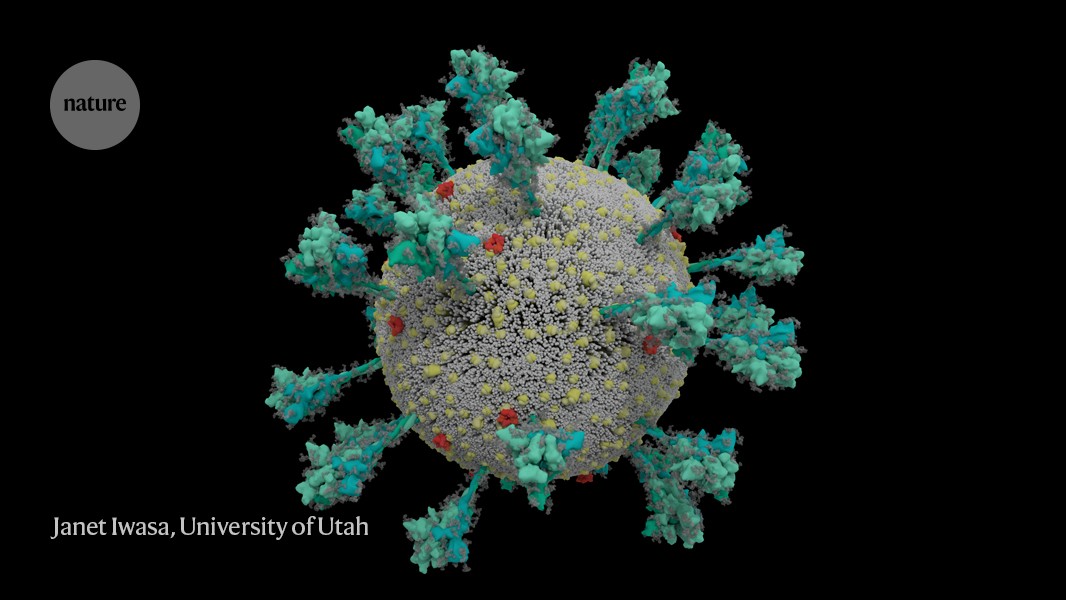

Although the known human coronaviruses can infect many cell types, they all mainly cause respiratory infections. The difference is that the four that cause common colds easily attack the upper respiratory tract, whereas MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV have more difficulty gaining a hold there, but are more successful at infecting cells in the lungs.

SARS-CoV-2, unfortunately, can do both very efficiently. That gives it two places to get a foothold, says Shu-Yuan Xiao, a pathologist at the University of Chicago, Illinois. A neighbour's cough that sends ten viral particles your way might be enough to start an infection in your throat, but the hair-like cilia found there are likely to do their job and clear the invaders. If the neighbour is closer and coughs 100 particles towards you, the virus might be able get all the way down to the lungs, says Xiao.

These varying capacities might explain why people with COVID-19 have such different experiences. The virus can start in the throat or nose, producing a cough and disrupting taste and smell, and then end there. Or it might work its way down to the lungs and debilitate that organ. How it gets down there, whether it moves cell by cell or somehow gets washed down, is not known, says Stanley Perlman, an immunologist at the University of Iowa in Iowa City who studies coronaviruses.

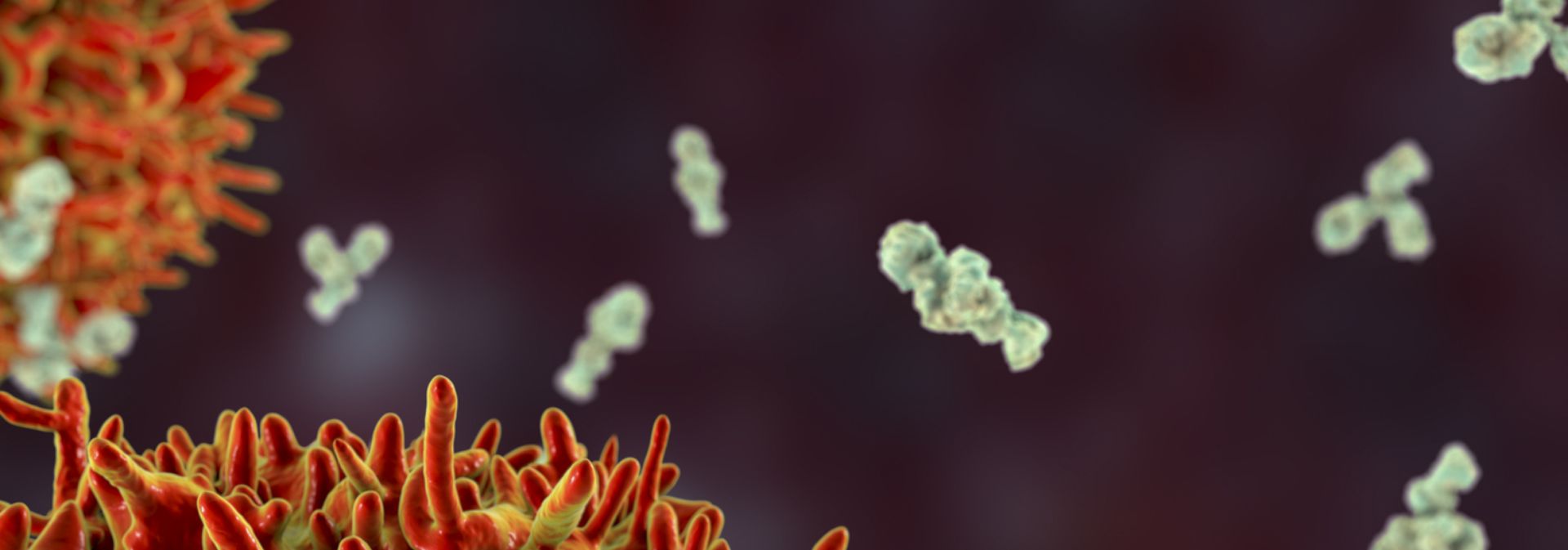

Clemens-Martin Wendtner, an infectious-disease physician at the Munich Clinic Schwabing in Germany, says it could be a problem with the immune system that lets the virus sneak down into the lungs. Most infected people create neutralizing antibodies that are tailored by the immune system to bind with the virus and block it from entering a cell. But some people seem unable to make them, says Wendtner. That might be why some recover after a week of mild symptoms, whereas others get hit with late-onset lung disease. But the virus can also bypass the throat cells and go straight down into the lungs. Then patients might get pneumonia without the usual mild symptoms such as a cough or low-grade fever that would otherwise come first, says Wendtner. Having these two infection points means that SARS-CoV-2 can mix the transmissibility of the common cold coronaviruses with the lethality of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. "It is an unfortunate and dangerous combination of this coronavirus strain," he says.

The virus's ability to infect and actively reproduce in the upper respiratory tract was something of a surprise, given that its close genetic relative, SARS-CoV, lacks that ability. Last month, Wendtner published results

8 of experiments in which his team was able to culture virus from the throats of nine people with COVID-19, showing that the virus is actively reproducing and infectious there. That explains a crucial difference between the close relatives. SARS-CoV-2 can shed viral particles from the throat into saliva even before symptoms start, and these can then pass easily from person to person. SARS-CoV was much less effective at making that jump, passing only when symptoms were full-blown, making it easier to contain.

These differences have led to some confusion about the lethality of SARS-CoV-2. Some experts and media reports describe it as less deadly than SARS-CoV because it kills about 1% of the people it infects, whereas SARS-CoV killed at roughly ten times that rate. But Perlman says that's the wrong way to look at it. SARS-CoV-2 is much better at infecting people, but many of the infections don't progress to the lungs. "Once it gets down in the lungs, it's probably just as deadly," he says.