When teams are deliberating on their draft boards -- specifically when looking at the top of the draft -- the position of the skater is often a very key question. Do they want a potential first-line center, or a potential No. 1 defenseman? John Tavares or Victor Hedman? Nail Yakupov or Ryan Murray? Nathan MacKinnon or Seth Jones? Sam Reinhart or Aaron Ekblad?

In 2015, after the top two picks go Connor McDavid and Jack Eichel, will the team picking third want forwards Dylan Strome or Mitch Marner, or will they grab top defensive prospect Noah Hanifin? The evidence favors the former.

The decision at the No. 3 slot comes down to two variables: First is the evaluation of the merits of the player’s own abilities, and second is the relative value of a player based on his position. The most important aspect of this is the actual value of the position at the NHL level.

On talent alone, Boston College blueliner Hanifin is either even with or a little above star OHL forwards Strome and Marner.

But to break the tie over who the No. 3 team should pick comes down to the positional variable, and there's evidence to suggest that grabbing a player that will be a top-line forward is a wiser investment than getting that top-pairing D-man. Here's why.

Forwards are more important than defensemen

In the 2014 edition of Rob Vollman’s Hockey Abstract, Tom Awad unveiled one of the most important pieces of research in hockey analytics in the past few years titled “What Makes Good Players Good?” As you might expect, it asked a simple, yet extremely important question: Who are the "good" players, and what attributes make them "good?"

One of Awad’s conclusions -- that forwards are much more important than defensemen -- was initially jarring:

“Results at even strength are driven primarily by forwards. This is not to say that offensive play is more important than defensive play; simply that, in the NHL, the players who contribute the most to outscoring the opposition at even strength are first-line forwards, not top-pair defensemen.”

To show this, Awad split up the league-wide ice time for forwards and defensemen into quarters and thirds respectively, and analyzed the differences between the tiers of ice time and their performance. With forwards, there were noticeable differences between the four tiers, but this was not the case for defensemen in the first two tiers, with only a moderate drop-off to the third. Awad showed that the difference between the highest and lowest tier forward groups was a 0.76 goal differential per 60 minutes, but the difference between the highest and lowest tier defensemen groups was only a 0.13 goal differential -- six times less!

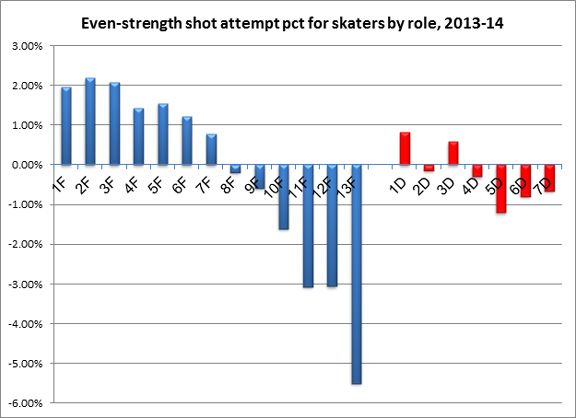

Another way to look at this is to take individual splits of shot differential for players when they were on the ice compared to their team when they were off the ice. To determine the role of players in the chart, I used each player's ranking within their team by even-strength ice time.

This echoes what Awad found in his research. The even-strength effects of forwards are more pronounced at the top and bottom of performance levels than they are for defensemen. Good forwards elevate a team and bad ones crush a team, and the effect is more intense than that of their defensive counterparts.

This does not suggest that particular star defensemen don’t impact teams in a significant way -- Zdeno Chara, Drew Doughty and Erik Karlsson come to mind -- or that there are no black-hole defensemen in the NHL.

But generally speaking, defensemen at the top of a team’s lineup impact their team much less than the top forwards on a team at even strength, and these differences remain even after adjusting for details like quality of competition and linemates.

When I asked one NHL executive what he thought about that chart, he said, “I’m not surprised. Good forwards are far more valuable than good defensemen, and if anything, when you’re drafting, forwards tend to be safer bets to pan out as well.”

The decision at No. 3: Hanifin or a forward?

At this point, it may seem like I am clearly pro-forward, but it's not that simple. There is still a balancing of the particular merits of the players that has to be done. Keep in mind that I advocated for Ekblad as the first overall pick of last year’s class.

Part of the debate centers on this question: Will Hanifin be a star defensemen, like those cited above, or merely the type of player that could slot in as part of a team's top pairing?

Relative to the abilities of an average under-18 defenseman, Hanifin has looked slightly more impressive than Strome or Marner have looked relative to an average under-18 forward. Hanifin had one of the best performances in the IIHF under-18 championships last spring for an underage player that isn't named Connor McDavid. He played in the top four of Team USA’s World Junior Championship team earlier this season as a double-underage player, which is extremely rare for a D-man from one of the competitive hockey countries.

He’s also been an all-situations, high-minutes player in one of college hockey’s toughest conferences (Hockey East). He grades as a much better skater than Strome and has the size (6-foot-2, 205 pounds) that Marner lacks; he also has a better two-way game than both right now.

Strome and Marner have been exceptional in their own rights. Their scoring has been among the very best under-18 seasons the OHL has seen in recent memory for draft prospects; Strome has 117 points through 65 games, while Marner is at 124 points through 62 contests. Their puck skill levels and offensive IQs are far greater than Hanifin’s, with Marner’s skating being at the same high level as the blueliner.

In prospect evaluations, player’s performance level relative to their position tend to be highly attractive to scouts. In addition, a player who performs well one to two years ahead of their age group during international play -- such as Hanifin has done -- immediately draws considerable attention. It’s no surprise that after playing ahead of their age group for a few seasons, goaltenders Jack Campbell and Andrei Vasilevskiy were first-round draft picks.

Taking all of this into account, some would argue that Hanifin should be in a tier above the forwards, even after what we have learned about the positional value. However, after balancing all the listed factors above, I am not convinced that Hanifin has had a more impressive track record than Strome or Marner, even given the great teammates they’ve had (Strome counts McDavid as a teammate, while Marner skates with top-flight Coyotes prospect Max Domi).

Being 20 percent better than an average defenseman prospect may not make you better than a forward who is 15 percent better than an average forward prospect. Hanifin has been more impressive as a defense prospect than Strome or Marner as forwards, but it hasn’t been by enough to outweigh the position advantage that the forwards inherently possess.

Strome and Marner are potential star forwards with a decent chance to be top-line players. Even though Hanifin could be a No. 1 defender, maybe even a top-10 D-man in the league, the upside does not exceed the alternative options, especially when you consider the rate at which defensemen bust relative to forwards. Lower ceiling, lower floor, in other words. For that reason, Strome or Marner is a better choice.

Looking ahead

When the call is close between a forward and defense prospect, take the forward. I’d define “close” as players who project to be around the same range relative to their position average. This is for reasons of predictability (forwards are safer bets), and in terms of actual on-ice value, as confirmed both by the analytics and by the NHL executive.

The NHL is a forwards league, where most (but not all) good teams are built from the faceoff dot to the sides and back, and not from the net and out. This applies at the draft table and in other player acquisitions.

It’s also the reason why when I look at the merits of the prospects available after McDavid and Eichel, I side with Strome and Marner being selected ahead of Hanifin this June.