But that is not what this is about at all? We arent picking ideal places to live. We are picking a world leader that would do the least harm world wide.

And your suggestion here is that China would be that country?

America has as much to do with the "peace" of the world as it had to do with starting the wars that happened before it was in charge.

Try telling someone in the middle east or east asia how peaceful and benevolent the American leadership has been. A large part of the world's population hates you for a very good reason.

I might be misreading him, but I don't believe he is telling anyone that the US is peaceful or benevolent. The benefits of US hegemony are not because the US is benevolent, after all; they happen because the US has (historically) seen them as beneficial to the US.

This is probably the best explanation I've come across:

Grand strategy is a set of ideas for deploying a nation's resources to achieve it's interests over the long run. The descriptor "grand" captures the large-scale nature of the strategic enterprise in terms of time (long-term, measured in decades), the stakes (the interests concerned are the large, important, and most enduring ones), and comprehensive (the strategy provides a blueprint or guiding logic for a nation's policies across many areas). Grand strategy is thus far less variable than foreign policy, which changes from one administration to the next or even within a single presidency (as when Ronald Reagan shifted from a hard line to a more accommodating approach to the Soviet Union in his second term). While foreign policy analysis is often preoccupied with such shifts, the study of grand strategy invites a longer-term view that looks broadly at all of the issues encompassed by the US approach to the world. That perspective reveals a set of core pillars that have underlaid US foreign policy for seven decades.

Ever since the dawn of the Cold War, the United States has sought to advance its fundamental national interests in security, prosperity, and domestic liberty by pursuing three overlapping objectives: (1) managing the external environment in key regions to reduce near- and long-term threats to US national security; (2) promote a liberal economic order to expand the global economy and maximized domestic prosperity; and (3) creating, sustaining, and revising the global institutional order to secure necessary interstate cooperation on terms favorable to US interests. The connection between essential American interests and these three larger objectives did not spring forth from the pen of George F. Kennan or any single strategist. It emerged from the rough-and-tumble process of solving more immediate problems, as US leaders progressively discovered the interdependence of security and economic goals and the utility of international institutions for attaining both.

The pursuit of those three core objectives underlies what is arguably the United States' most consequential strategic choice: to maintain security commitments to partners and allies in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. US administrations have consistently maintained that the security commitments in these three key regions are necessary to shape the global environment and thus advance the grand strategy's three core objectives. During the Cold War, the commitments served primarily to prevent the encroachment of Soviet power into regions containing the world's wealthiest, potentially most powerful, and resource-rich states. But it is only in hindsight that Cold War containment seems so simple. As John Lewis Gaddis demonstrated, containing Soviet military might demanded economic recovery, which in turn appeared to require military assurances to instill the confidence needed to save, invest, and trade. So even though the Soviet military threat was not imminent (it was initially widely assumed that Moscow would be in no position to attack for a decade, at least) the United States found itself organizing political, military, and economic activity around the world to assemble a "preponderance of power" over its Soviet adversary.

Discrete choices about how to respond to immediate challenges ultimately added up to a choice for a grand strategy of deep engagement. Each choice entailed rejection of an alternative - and these alternatives, taken together, would have added up to a different global strategy. The United States worked long and hard to foster an open global economy rather than adopting a noncommittal stance or, as it did in the 1930s, actually taking very significant actions that moved the world toward economic closure. In turn, the United States made a decided effort to advance necessary cooperation through international institutions rather than relying only a mix of ad hoc cooperative efforts and a unilateral approach. And in the security realm, the United States opted for formal alliances and a significant forward presence in Asia and Europe rather than relying entirely on local actors to prevent either of these key regions from falling under the domination of a hostile power.

In the security realm, the problem with pursuing the alternative, less engaged "offshore balancing" approach in Asia and Europe was that local states were too weak to counter Soviet power without US help, and it was ultimately hard to see how to make them strong enough to balance the Soviet Union on their own without scaring neighbors and thus ruining alliance cohesion. In Europe, making frontline Germany strong enough to check the Soviet Union without a major US presence would have demanded German rearmament and acquisition of nuclear weapons, which risked alienating France and other neighbors and wrecking the alliance. To paraphrase Lord Ismay's famous dictum regarding NATO'S purpose, US officials concluded that keeping the Americans in was the ideal method for keeping the Soviets out while simultaneously keeping the Germans down.

The same story replayed in the looser Asian alliance setting, as US officials understood that a move by Japan toward remilitarization and nuclearization would radically destabilizie the allianes that were thought just barely able to contain Soviet and Chinese power. US leaders concluded that the only awy to achieve "alignment despite antagonism" among prospective US partners was through active regional security management.

There are clear global commons benefits here—it reduces interstate conflict, it reduces arms racing, it reduces nuclear proliferation, and it maintains institutions for global cooperation and resolution of conflicts—but for the US those benefits are ancillary. But they are real. Regionally-focused security research in East Asia, for instance, agrees that the abrogation of US security commitments would lead to major-power security competition, militarized crises, and competitive support for rival smaller powers. In Europe, NATO's Article 5 is "an important part of the current institutional equilibrium in Europe"; its abrogation could potentially tear apart the security policies of major European powers and it will cause a collapse of concerted power in Europe. As one analyst puts it, strategic decoupling from Europe by the US "will incapacitate European foreign policy, invite Russian and other outside meddling, and compel the United States to sort out European affairs rather than mobilizing an Atlantic partnership for the management of global affairs." In Eastern Europe, basic political stability in, say,

Latvia is deeply dependent on US involvement.

Consider the case of Latvia. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has managed an uneasy balance between its ethnic Latvian majority and a large Russian minority. Ethnic Russian leaders have pursued political accommodation and supported the country's Western orientation. Ignoring this success, Mr. Trump would give pro-Russian hotheads an opening — an incentive to challenge their moderate rivals, to attract Russian aid and media attention, and to threaten national unity. Last year, after an American military unit arrived in Latvia for a NATO exercise, the mayor of the capital, Riga — who heads the ethnic Russian party — told me he was glad to welcome the group with a visit aboard the Americans' ship. If Latvia's place in NATO became a divisive issue, would the mayor make such a gesture again?

Those seeking to divide the country are not the only ones who might act differently if Mr. Trump were president. I have heard Latvian security officials say that Mr. Putin's overnight seizure of Crimea in 2014 altered their thinking about how to keep Russia's "little green men" from doing the same thing in Latvia. These officials now think they must be ready to snuff out threats before they materialize. Worry that Washington might not be with them in a crisis might well encourage harsher crackdowns. Hair-trigger policy is rarely smart politics, but that's where Mr. Trump's ideas lead.

By telling Latvians not to count on the United States, he encourages participants in an increasingly stable and legitimate political system to try confrontation rather than compromise. This pattern is hardly confined to the Baltic States. In Central Europe and the Balkans, doubts about American commitment could foster conflict. Tensions might build slowly, but by the time a problem came to the president's desk in Washington, it would be more dangerous than it is today. A President Trump might blame vulnerable allies. The real responsibility would be his.

American policy in Central and Eastern Europe since the Cold War ended has helped to create stability, prosperity, moderate politics and ethnic accommodation in countries that have rarely known them. These are remarkable achievements. It would be crazy to put them at risk.

Even in the Middle East, where the US's recent record is worst, most analyses predict a significant increase in nuclear proliferation; one of the reasons why the US should not fear a "proliferation cascade" if Iran were to obtain nuclear weapons is the US' security assurance for Iran's regional rivals. Additionally, Washington is able to use its partners' security dependence to force cooperation. For instance, Egypt and Israel both engaged in a peace process and in Israel's case made territorial concessions because of economic benefits, aid, and security assurances by the US to both sides. This was also true more recently in 2011 between Israel and Turkey, and even indirectly between Israel and Hamas (where the US had ties with both Israel and Turkey, Qatar, and Egypt). It is worth noting that the current level of US involvement in the region (e.g. post-2003 levels) is not necessary to achieve those kinds of effects; even the 1991–2002 period was probably excessive. But absent hegemonic stability provided by the US, you can imagine the open competition for regional dominance that would ensue between the large powers in the region.

And again, the US does not do these things because it is peaceful or benevolent or good. It believes that this system is beneficial to itself. And it is. US households represent 45.9% of the ownership of the top 500 multinational corporations; NA households are 41% of all global household assets and 42% of the world's millionaires as of 2011—despite the NA, European, and Asia-Pacific shares of GDP being roughly equal at a quarter each; the US has created a largely monopsonistic arms trading system for most of the world that has resulted in deeply asymmetrical interdependence between the US and its allies, where the US would suffer far less than its allies if defense production ties were suddenly cut. The US uses this asymmetric interdependence as influence by keeping allies dependent and excluding rivals (e.g. Russia and China), not just from its own market but using its market power to force other states to do the same.

The US uses these security commitments as leverage in negotiations with other states. It uses these security arrangements as leverage when it exercises leadership [read: power] in global institutions. It uses its position to rewrite global rules when it suits itself—for instance, as it did when it altered the rules of the Bretton Woods regime in 1971–1973 to change its bargaining position and force its creditors to make concessions. And yet, the hegemonic leadership that makes this possible for the US also makes it more likely that institutionalized cooperation and global order will be more dynamic and able to adapt with a hegemon that is able to provide leadership in pushing for necessary changes.

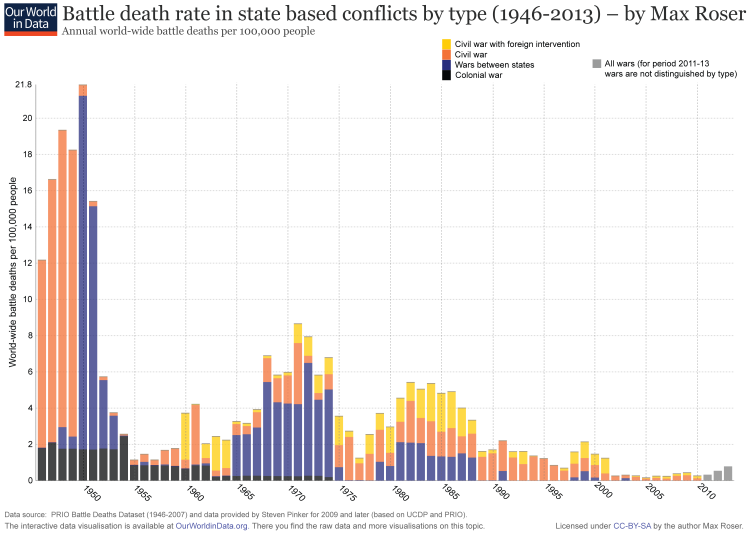

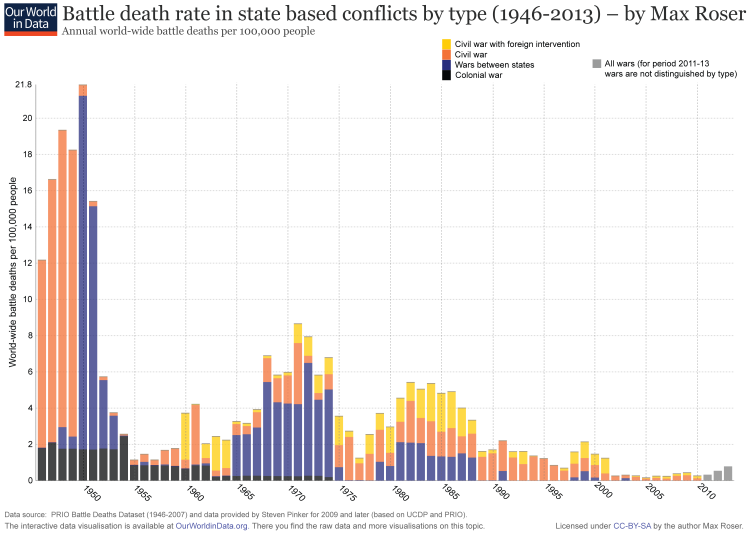

I'm not saying that the US' role has been perfect. It was responsible for a lot of the deaths you see on the chart I posted in response to Liha below between the end of World War II and the end of the Cold War. It has also been responsible for smaller scale atrocities around the world and especially in its own backyard in the form of destabilization, coups, and supporting dictators and strongmen. For countries that have had to experience this side of US hegemony, of course the fact that US hegemony has its upsides for other countries doesn't really matter. But I think the question here is not whether the US is good. I think the question is how would its potential replacements compare. Would China be less likely as a global hegemon to destabilize smaller countries that it views as opposing itself? Would China be willing to create systems of security commitments to increase regional stability? Would China similarly promote interstate cooperation and adherence to global institutional rules? I don't think that there's a credible argument that China would be better on these questions.

If we would have a multipolar system whereby US, China, India and Russia all have relative the same power status with no single one able to dominant, it would naturally lean more towards cooperation.

This does not follow. We have had a multipolar system before; we had the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the Franco-Prussian War, the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and World War II over the course of just one part of that long history. If you go back more, you'll find even more. Since the end of the multipolar system, we have not had wars between major powers. Since the beginning of the unipolar system (after the fall of the USSR), we've seen historic lows in battle death rates:

I don't know exactly whether or not the beginning of a new multipolar system will be more stable than it was before. Maybe nuclear weapons will create a holding pattern. Or maybe it will encourage nuclear proliferation and create more destabilization and distrust. But the idea that parity will lead to cooperation isn't something you should rely on, especially since near parity in the bipolar system while not leading to open war between the rival states did lead to intense arms racing and multiple crises that nearly led to nuclear war.