SomeNorseGuy

Gold Member

How to accommodate neurodiversity in video game development

"It's like handing someone the wrong game controller and then judging them for not being able to play the game."

Some outtakes about here and her views:

Katherine Mould, senior talent acquisition specialist at Keywords Studios, says she was diagnosed with ADHD at age six.

"One of the things that I will always scream from the rooftops is you do not need a diagnosis to be neurodivergent," she says. "It's not something you need a doctor to tell you you have. It's just the way your brain works."

"The diagnosis is not what matters, right? You wouldn't walk up to somebody and tell them they weren't who they were because they didn't have a piece of paper saying that."

In a talk at Develop:Brighton entitled 'Superpowers in Diversity: Managing Mental Health and Neurodiverse Teams for Success', Mould outlined ways in which employers and peers could help to accommodate and encourage neurodiverse teams.

Some of her talking points:

"All neurodiversity is a different way of thinking. It's different brains that have different processing mechanisms, and [the term] recognises that neurological differences are normal and valuable within the human experience. It doesn't mean that somebody has a problem or that they can't process information. It just means that they might do it faster, better, or differently." But she notes that neurodivergent people tend to hop between jobs, only lasting a year or 18 months before they "either get burnt out or they get so overwhelmed that they start making mistakes".

"They cannot physically do what their neurotypical teammates do in those environments, and they'll either leave or they'll get fired."

This is why she is such an advocate for accommodating neurodiversity in the workplace – because by failing to do so, employers are missing out on neurodivergent 'superpowers'. But expecting neurodiverse people to thrive in an environment designed for neurotypical people is destined to fail, she thinks. "It's like handing someone the wrong game controller and then judging them for not being able to play the game."

"We design hiring loops and workflows and team cultures around assumptions that people are extroverted, fast paced, and noise tolerant, comfortable in social situations, and comfortable with ambiguity," she says. Then, when a neurodiverse person struggles, "we tend to frame it as a flaw in the individual."

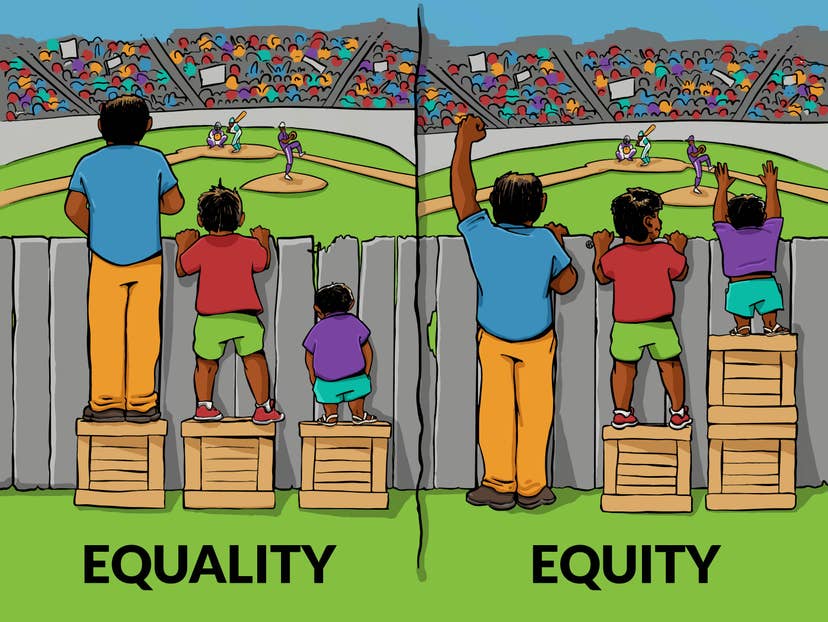

"Equality means that everybody gets the same thing. Equity means that everybody gets what they need to succeed, essentially. So I would like to see equitable hiring practices where the questions are based on what we need for the job and the skills."

Illustration of equality versus equity that shows three people of different heights attempting to see over a fence to watch a baseball game. "That's the visual representation that sticks for me: for equity, it's giving people what they need."

She emphasises the importance for employers to provide quiet spaces. But if that's not possible, then "even just giving the employee perk of noise-cancelling headphones can make all the difference".

Mould also emphasises that meetings can be tricky. Her personality means that she's often the most talkative one, but she points out that loud people "don't always have the best ideas – sometimes it's our quiet friends in the corner who are overwhelmed by the social situation, or they're having a hard time processing".

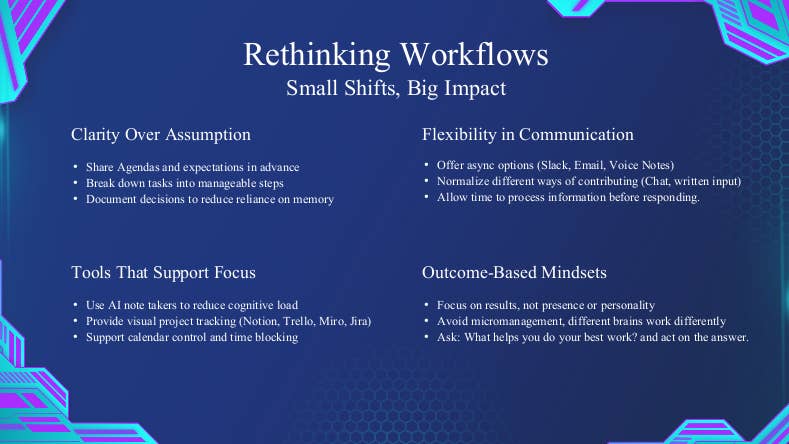

She emphasises that providing clear expectations for exactly what each employee needs to achieve is key for accommodating neurodiversity. Vague or unclear goals are unhelpful: expectations need to be spelled out precisely.

"Don't say, 'Hey, I want a report on Friday'," she explains. "That doesn't help me. What does that look like? Do you want that input form? Do you want an entire task list? What do you want? Just be as explicit as you can – but not micromanaging."

The same rule applies to feedback and employee evaluations. "Indirect feedback that relies on reading between the lines, this is my most hated thing," says Mould.

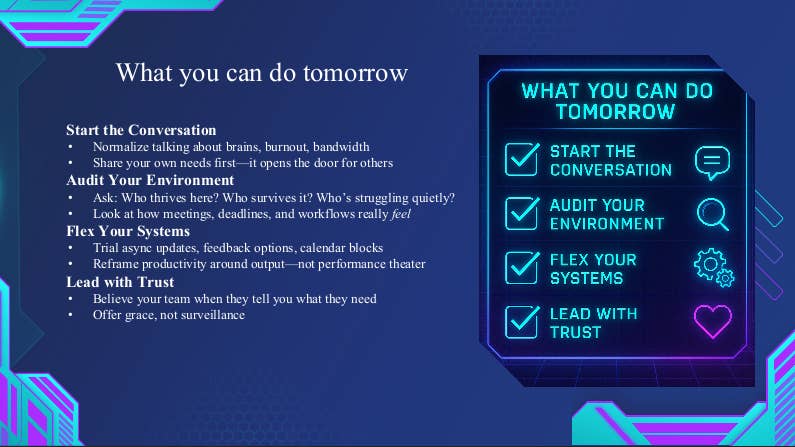

Conclusion:Still, in order for employees to benefit from this kind of support, they have to feel safe enough to access it.

"Safety is what's experienced, right?" says Mould. "You can provide all the supports you want, but if people aren't using them, they don't know how to access them, they do not feel safe enough to do so – that's not safe."

"People do not use accommodations when they fear judgement."

"There have been numerous times in my career where I have been afraid to ask for what I might actually need, for fear of what might come after."

Above all, she thinks that the number one thing people managers need to do is provide grace.

"Grace is just allowing people to be who they are, and not punishing people for those differences," she says.

"It's general basic human decency in a lot of ways. Allowing people to make mistakes and learn from them, and giving grace for growth."

Some of my best friends can probably be classified as neurodivergent, but if these kind of talks actually gets taken seriously in dev circles ...phew, slow dev cycles would get even slower.

Safe space to all and have a great Sunday.