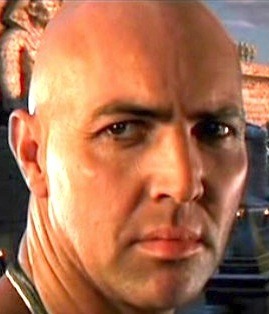

Arsenal supporters are unlikely to have fond memories of André Santos. The Brazilians two-year spell at the club, between 2011 and 2013 included 13 Premier League starts, one attempted high-speed getaway on the M25 and one ill-advised half-time shirt swap with Robin van Persie. All in all, not a great return for the £6m Arsène Wenger paid to secure the defenders services from Fenerbahce.

Since leaving Arsenal, however, life has got worse for Santos. A lot worse. Now plying his trade back in Brazil, the left-back was last week at the centre of a series of events that will surely cause the harshest of his critics to side with him. Upon leaving the Estádio Beira-Rio in Porto Alegre on 20 July, he was beaten up by a group of Flamengo fans furious that their team, which he had represented for almost exactly a year, had just been trounced 4-0 by hosts Internacional a result that left the Rio side entrenched at the bottom of the Campeonato Brasileiro.

I am absolutely saddened and shaken by what happened. It [the aggression] was the work of a minority of supporters but as a professional footballer and a father I never expected to experience a situation like that. I didnt see the supporters coming and when they started hitting me the only thing I could think of was to try to protect my head, said Santos.

That was far from the end of Santos misfortune. Only two days after the incident outside Beira Rio, one of the arenas used in the 2014 World Cup, Flamengo released the 31 year-old, a decision announced by the player in an interview with a daytime TV Globo programme that can only be described as a bad Brazilian version of Loose Women. The fact that the clubs directors quickly denied the contract termination in public while briefing the journalists off the record that they wanted to send the player packing only makes the story sadder.

From being hailed as a possible successor to Roberto Carlos in the Seleção and actually replacing the former Real Madrid star at Fenerbahce in 2009, Santos now finds himself surplus to requirements even at a club in Flamengos grim position. Santos was given the first of his 24 caps for Brazil in 2009 by Dunga, during the new Brazil coachs first spell in charge, but his international hopes were all but killed in 2011 after he missed one of the four penalties in a Copa América shootout defeat to Paraguay and followed that with a poor display in a friendly against Germany that somehow did not end with the cricket scoreline that Thomas Müller and company imposed in Belo Horizonte.

Santos is hardly a veteran, but it would be an immense surprise if his career did not simply fade away even if he has surprised a few people before. After failing to establish himself at the Emirates despite an interesting first season, he shot himself in the foot with a metaphorical bazooka with that ill-judged decision to swap shirts with Van Persie during the Dutchmans bitter reunion with Arsenal just months after his move to Old Trafford.

His intended gesture of sportsmanship was followed, three months later, by a loan move to Grêmio. But Santos actually threatened to rekindle his career in Brazil: after spending only five months with Grêmio he moved to Flamengo and helped the club to a heroic Brazilian Cup title last year. But then things turned sour: after only 28 games and a poor run for Flamengo this season, he became an object of hatred for the clubs fans.

Poor form or not, nothing can justify the despicable behaviour towards the full-back in Porto Alegre. Santos plight exposes a problem that Brazilian authorities underestimated in the buildup to the World Cup. The brand new arenas were built according to standards applicable to situations where crowd control is pristine. Last year, a fight between Corinthians and Vasco supporters at the Mané Garrincha in Brasília highlighted the challenges faced by the domestic game at times when crowd violence still erupts.

Santos was not attacked inside the Beira-Rio itself after eschewing a lift to the airport on the team bus, he was about to enter a private car that was waiting by the stadiums media entrance. The fact that he was left so exposed raises serious questions that are independent from the fact that his career has never returned to the heights seen when he featured heavily in Brazils 2009 Confederations Cup-winning campaign and was considered a certainty for the 2010 World Cup squad.

Even if it could be argued that Santos has lacked the maturity, rather than merely the quality, to persevere in European football and fulfil what was expected of him in Brazil, the more pressing concern surely lies in how Brazils football authorities can protect the areas around the countrys stadia and curb supporter incursions that, in this instance, crossed a line in the most dangerous fashion.