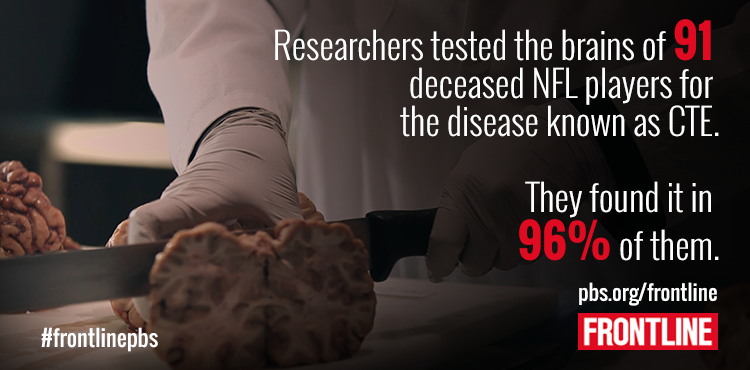

A total of 87 out of 91 former NFL players have tested positive for the brain disease at the center of the debate over concussions in football, according to new figures from the nations largest brain bank focused on the study of traumatic head injury.

Researchers with the Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University have now identified the degenerative disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, in 96 percent of NFL players that theyve examined and in 79 percent of all football players. The disease is widely believed to stem from repetitive trauma to the head, and can lead to conditions such as memory loss, depression and dementia.

In total, the lab has found CTE in the brain tissue in 131 out of 165 individuals who, before their deaths, played football either professionally, semi-professionally, in college or in high school.

Forty percent of those who tested positive were the offensive and defensive linemen who come into contact with one another on every play of a game, according to numbers shared by the brain bank with FRONTLINE. That finding supports past research suggesting that its the repeat, more minor head trauma that occurs regularly in football that may pose the greatest risk to players, as opposed to just the sometimes violent collisions that cause concussions.

But the figures come with several important caveats, as testing for the disease can be an imperfect process. Brain scans have been used to identify signs of CTE in living players, but the disease can only be definitively identified posthumously. As such, many of the players who have donated their brains for testing suspected that they had the disease while still alive, leaving researchers with a skewed population to work with.

Even with those caveats, the latest numbers are remarkably consistent with past research from the center suggesting a link between football and long-term brain disease, said Dr. Ann McKee, the facilitys director and chief of neuropathology at the VA Boston Healthcare System.

People think that were blowing this out of proportion, that this is a very rare disease and that were sensationalizing it, said McKee, who runs the lab as part of a collaboration between the VA and BU. My response is that where I sit, this is a very real disease. We have had no problem identifying it in hundreds of players.

In a statement, a spokesman for the NFL said, We are dedicated to making football safer and continue to take steps to protect players, including rule changes, advanced sideline technology, and expanded medical resources. We continue to make significant investments in independent research through our gifts to Boston University, the [National Institutes of Health] and other efforts to accelerate the science and understanding of these issues.