One day this spring, over lunch in Chicago, David Axelrod offered up a concise summary of Team Obamas prevailing view about the race ahead against Mitt Romney. We have the better candidate, and we have the better argument, Axelrod told me. The question is just whether the externalities trip us up. For months before that and every day since, the litany of potential exogenous shocksfrom the collapse of the eurozone to a hot conflict between Israel and Iran to a succession of brutal jobs reportshas kept Axelrod and his colleagues tossing and twitching in their beds at night. For all their overt confidence, the Obamans are also stone-cold paranoiacs, well aware of the iron law of politics enunciated long ago by the poet Robert Burns: The best-laid schemes o mice an men / Gang aft agley. Which, for those unversed in archaic Scottish, translates roughly as Shit happens.

And so it does, with the past week proving another maxim: that when shit rains, shit pours. In the space of 72 hours, what began, horrifically enough on September 11, with the murder of four Americans (including one of our best and bravest, Christopher Stevens, the U.S. ambassador to Libya) at the consulate in Benghazi spiraled into a region-wide upheaval, with angry Muslim protests directed at American diplomatic missions erupting in sixteen countries. Suddenly, the president was facing just the kind of externality that his team had been bracing for: a full-blown foreign-policy crisis less than eight weeks out from Election Day. And a campaign marked by stasis and even torpor was jolted to life as if by a pair of defibrillator paddles applied squarely to its solar plexus.

Moments like this are not uncommon in presidential elections, and when they come, they tend to matter. For unlike the posturing and platitudes that constitute the bulk of what occurs on the campaign trail, big external events provide voters with something authentic and valuable: a real-time test of the temperament, character, and instincts of the men who would be commander-in-chief. And when it comes to the past week, the divergence between the resulting report cards could hardly be more stark.

Anyone doubting the potential significance of that disparity need only think back to precisely four years ago, when the collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered a worldwide financial panic. In the ten days that followed, Obama put on a master class in self-possession and unflappability under pressure; his rival, John McCain, did the opposite. When the smoke cleared, the slight lead McCain had held in the national polls was gone and Obama had seized the lead. Though another month remained in the campaign, the race was effectively over.

For Romney, the first blaring sign that his reaction to the assault on the consulate in Benghazi had badly missed the mark was the application of the phrase Lehman moment to his press availability on the morning of September 12. Here was America under attack, with four dead on foreign soil. And here was Romney, defiantly refusing to adopt a tone of sobriety, solemnity, or seriousness, instead attempting to score cheap political points, doubling down on his criticism from the night before that the Obama administration had been disgraceful for sympathiz[ing] with the attackerscriticism willfully ignoring the chronology of events, the source of the statement he was pillorying, the substance of the statement, and the circumstances under which it was made.

That the left heaped scorn on Romneys gambit came as no surprise. But the right reacted almost as harshlywith former aides to John McCain, George W. Bush, and Ronald Reagan creating an on-the-record chorus of disapproval, while countless other Republican officials and operatives chimed in anonymously. This is worse than a Lehman moment, says a senior GOP operative. McCain made mistakes of impulsiveness, but this was a deliberate and premeditated move, and it totally revealed Romneys character; it revealed him as completely craven and his candidacy as serving no higher purpose than his ambition.

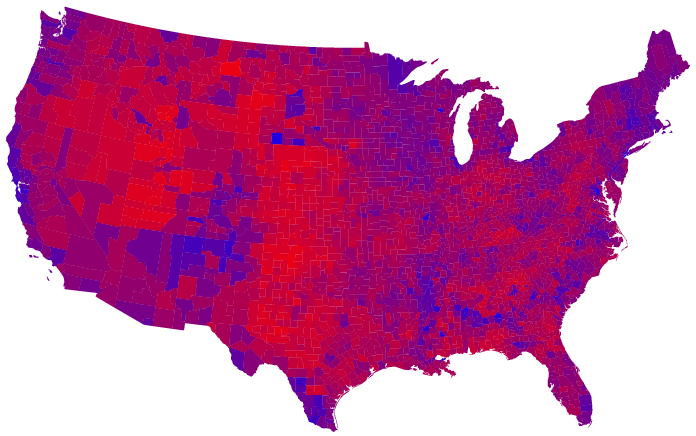

This bipartisan condemnation would have been bad enough in itself, but its negative effects were amplified because it fed into a broader narrative emerging in the media across the ideological spectrum: that Romney is losing, knows he is losing, and is starting to panic. This story line is, of course, rooted in reality, given that every available data point since the conventions suggests that Obama is indeed, for the first time, opening up a lead outside the margin of error nationally and in the battleground states. So the press corps is now on the lookout for signs of desperation in Romney and is finding them aplentymost vividly in his reaction to Libya, but even before that, in his post-convention appearance on Meet the Press, where he embraced some elements of Obamacare (only to have his campaign walk back his comments later the same day).