Antiochus

Member

A excellent piece by the WSJ regarding the attitudes and expectations of young 20 somethings regarding whether to buy health insurance on the new exchanges.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324263404578613700273320428.html

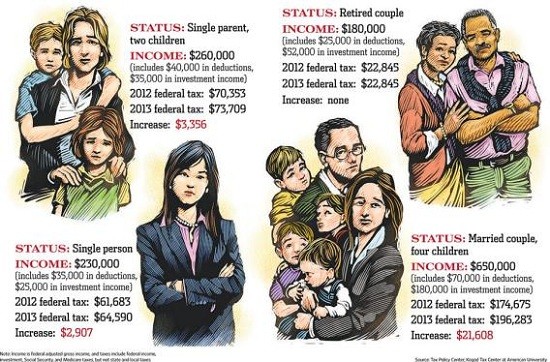

The website also features a great interactive on personal examples as to how the actual income based subsidy will (or in many cases, will not) work:

http://projects.wsj.com/documents/PORTLAND1307/

There are three main problems with Obamacare as it now stands;

1. We were told at the beginning that almost everyone's insurance premiums would drop if not at least stabilize, and that generous subsidies will be given up to a good income level. Then the message got switched that certain upper middle classes will have to pay more. Then it was the young subsidizing the old. Now the message seems to the young and healthy with incomes of barely $35K a year are expected to significantly subsidize their peers making $15K a year. Nearly all the young people 2-3 years were expecting a uniform decrease in their costs AND major subsidies for them.

2. In any case, trying to rely on those making ~$30K a year to prop up the system is folly. Paying $100 4-5 years ago was already a burden, now trying to pay $150-200 with a $5000+ deductible is even worse, and they get little to no subsidies whatsoever. The economy has not improved, wages are stagnant and many cases undergoing deflation, and its expected those people have plenty to spare?

3. Finally, the fatal flaw is that it assumes that merely slowing down the cost inflation, or perhaps somewhat stabilizing it, will patch up the healthcare system. Unfortunately, one ultimately needs a income of sorts in order to pay for any of those costs, no mater the level of subsidies or cheapness of the premiums. Even more unfortunately, as global economic forces and technological "progress" continues to ravage incomes and employment levels, the healthy core of payers will continue to decrease until this current Obamacare system is no longer tenable, because there will no longer be any sort of stable working/middle classes capable of paying even a modicum amount to float it.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324263404578613700273320428.html

The success of the new health-care law rides in large measure on whether young, healthy people like Gabe Meiffren, a cook at a Korean-Hawaiian food cart, decide to give up a chunk of disposable income to pay for insurance.

After getting a peek at rates being offered for fall, the 25-year-old man said he would have to peel back "expenses that aren't life or death, like records and concert tickets," or whiskey sours at the Horse Brass Pub down the street.Mr. Meiffren, who hasn't seen a doctor in more than a year, isn't sure buying insurance is worth it, despite a federal penalty for failing to buy coverage, starting in January.

President Barack Obama's signature initiative rests on what Mr. Meiffren and his peers choose. If flocks of relatively healthy 20- and 30-somethings buy coverage, their insurance premiums will help offset the costs of newly insured older or sicker people who need more care. If they don't, prices across the U.S. could spike.

Traditional insurance industry tools for managing risksuch as charging sick customers higher pricesare banned under the law, raising the importance of attracting young, healthy buyers.

The new law employs a carrot-and-stick approach: Federal subsidies will be available to some lower-income workers. And most of those who ignore the law next year must pay an annual penalty, based on income, that begins at $95 and climbs dramatically in the years that follow.

Interviews here with more than two dozen single workers of modest income between 24 and 31 years old suggest that insurance plans will be a hard sell. Subsidies for 26-year-old workers range from $118 a month for someone earning under $16,000 to less than $1 a month for one earning $26,500, according to an analysis of insurance data.

For Mr. Meiffren, the cheapest available insurance plan he could buy with the subsidies would cost him $116 a month, with a $6,350 annual deductible. His subsidy would total $14 a month, based on his $25,000 annual income."I'm healthy, so it's not in the budget," Mr. Meiffren said after the lunch rush. He lost a full-time joband his insurancelast fall. He said he moved to Portland from Los Angeles in March, looking for "a better vibe" and a lower cost of living.

Nationwide, there are 11.6 million people ages 18 to 34 who are uninsured, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. The federal government's challenge this fall will be getting them to buy health-care coverage, which many consider a luxury they can do without. Hospitals already must treat all emergencies, and uninsured patients are responsible for the bills.New insurance company filings approved by Oregon regulators this month offer a first look at the actual price tags for individual consumers, who can begin shopping for insurance in October through new marketplaces called exchanges.

Insurers set different rates in each state for plans they will be offering through the exchanges. Some states are running their own exchanges; others will be run by the federal government.

Portland could be an early measure of how young people will respond to the new coverage requirement. While some states have published partial or preliminary data, Oregon is among the first to set final rates.

Roughly 100,000 of Oregon's 560,000 uninsured people are expected to buy individual coverage on the exchanges. The state's new marketplace still must certify the plans.

"For healthy young people, I believe that these new rates are not likely to be attractive enough" compared with the no-coverage penalty, said John W. Rowe, chief executive of the health insurer Aetna AET -1.97% until 2006 and a health policy professor at Columbia University, speaking broadly about the marketplaces.

A Wall Street Journal analysis of the state's insurance data shows a mixed bag for this crucial demographic. Rates for many of the more than 100 plans available to individual shoppers in Portland are less than expected by many skeptics, who predicted the law would send prices soaring, the Journal found. But so are the federal premium subsidies.

The subsidies disappear altogether for single people under age 30 earning much more than $26,000 because of the way the law pegs them to specific plans on each state's exchange. That income threshold in Portland is nearly $20,000 lower than expected under the law, which calls for people earning up to about $46,000 to be eligible for subsidies.

The subsidies for young single people were unexpectedly low here in part because one insurer, Moda Health, offered two inexpensive plans that set a benchmark for the subsidies. It is a strategy that could attract price-sensitive shoppers. Experts said insurers elsewhere might also seize on the approach.

As directed by the law, insurers will offer three levels of coverage through the exchanges, from minimal benefits, called bronze, to midlevel plans, or silver, to robust coverage, gold.

All the plans will cover such benefits as hospital services and maternity care. While some plans can have deductibles of more than $5,000, consumers' total out-of-pocket costs are capped at less than $6,350 for single people. Some low-income people will see additional subsidies to reduce their deductible.

People under age 30 can buy bare-bones plans that only cover catastrophic illness that might be cheaper than bronze plans, but they come with higher deductibles and no subsidies.

Premiums will rise for some young people, compared with current rates, while generally falling for older and sicker people. Currently, a 26-year-old Oregon resident can pay less than $100 a month for coverage that carries deductible levels as high as $10,000.

In the new plans, prices for a 26-year-old nonsmoker will range from $133 a month for a bronze-level plan offered by Moda Healthwhich has a $6,350 deductible and $45 copaymentsto about $305 for gold-level plans sponsored by Trillium Community Health Plans that have a $1,300 deductible and $20 copayment.

"I'd love to get insurance," said Tom Daly, a 28-year-old who opened WTF Bikes in southeast Portland in 2009. After discussing details of the law, Mr. Daly said he would probably pay the no-coverage fine next year, but buy coverage before 2016, when the penalty rises.Mr. Daly pointed out another challenge for the government. Young people, he said, haven't paid attention to the new law.

"I wake up, come here and work, go home, watch an episode of 'Battlestar Galactica,' and go to sleep. That's my life," he said. "I don't have time to stop and spend three hours to figure out how it is going to affect me."

A White House-backed campaign to spread the word to young people is ramping up for fall, federal officials said.

One tactic is to remind young people they aren't invincible in such scenarios as, "Oh my God! I hurt my knee in a pickup basketball game," said Julie Bataille, the health department official overseeing the campaign.

Officials running Oregon's marketplace, called Cover Oregon, unveiled a $3 million ad campaign featuring a performance by Laura Gibson, a local folk singer. She penned an anthem with the refrain "live long in Oregon."

"There's this theory that it's going to be impossible to convince them, but there's a lot of young people who think it's important to have insurance," said Amy Fauver, chief communications officer for Oregon's federally funded, state-run marketplace.

For some people, however, the math doesn't work. The $29,000 annual pay that Jonathan Scarboro expects to earn this year as a $14-an-hour, full-time mechanic at Veloculta combination bike shop and cafe-baris too high for a subsidy. The cheapest plan would cost him $147 a month and carry a $6,350 deductible for many services, including hospital care. For $172 a month, he could buy a plan with a $2,500 deductible. (comment: Oops !)

"I'm not going to pay for that," said Mr. Scarboro, age 30. "It breaks down to: Can I afford it? And, am I getting my money's worth?"

The uninsured can get care at pay-by-the-visit urgent care centers and clinics. "I've already seen quite a few" young, lower-wage workers, said Carolyn Nowosielski, a nurse practitioner at the Oregon Health & Science University clinic that here opened in June.

For many people earning less money, the new coverage looks like a bargain. Michelle Taylor, 26 years old, makes a bit more than $17,000 a year from her new photo-booth rental business, HappyMatic Photo Booth.

She is eligible for a $103-a-month subsidy and could buy the cheapest silver plan for as little as $52 after the subsidy. A separate subsidy under the law also limits the deductible for low-income people. For Ms. Taylor, that will yield an annual deductible as low as $100 a year.

"That sounds awesome to me," she said. "My parents would be so pleased."

The website also features a great interactive on personal examples as to how the actual income based subsidy will (or in many cases, will not) work:

http://projects.wsj.com/documents/PORTLAND1307/

Mr. Meiffren lost insurance along with a full-time restaurant job last September. Since then, he's been uninsured. "It just hasn't been in the budget," he says. A $50-a-month policy might be a good deal in his view.

But, under the law, Mr. Meiffren will pay much more. His income limits the amount of subsidies he could receive in Oregon to about $14 a month. That means, for the cheapest bronze-level coverage option, he'd still have to pay $116 a month.

"It's not something I could do currently, but it's not the worst thing ever," he said. To keep coverage offered by his former employer, he said, he'd have to pay north of $400 a month. To afford insurance, he says he'd have to peel back "expenses that aren't life or death, like records and concert tickets" or trips to the bar down the street for whiskey sours./

Jonathan Scarboro, 30 Bike mechanic, $29,000 a year

A relatively higher earner by the standards of Portland's bike culture, Mr. Scarboro makes too much to qualify for federal subsidies at all--but not enough that buying coverage is a no-brainer. The lowest-cost option would run him $147 a month. A mid-level plan that covers more services would cost $240, while an array of other options fall in between.

His reaction to those premiums: "One hundred dollars to $150 would be reasonable," he said. But, faced with the annual deductibles tied to those plans--between $2,500 and $5,000 for most services--his math quickly changed. "I'm not going to pay for that," Mr. Scarboro said. "It breaks down to, can I afford it, and am I getting my money's worth? At a certain point, you expect health insurance to be, like, you can go to the doctor."

Mr. Scarboro, a Florida native who moved to Portland last year and plans to stay, says the flexible slice of his budget includes about $200 a month in spending for beer, bicycle parts and coffee. He saves another $150 to $250 a month, but insurance would eclipse that, he said.

Erin Weaver, 30, Waitress, $17,000 a year

When Erin Weaver's college-sponsored insurance runs out in September, she'll be on the market again for new coverage. The cheapest plan she can find now runs about $250 a month.

"My parents are all, like, you have to have health insurance," she said, "but that's a car payment." Her relatively low income--$17,000 or so a year earned from waiting tables--means she'll see prices fall next year dramatically because of subsidies. At that level, she'd be able to buy a silver-grade health plan for as little as $46 a month, after factoring in a $123-a-month subsidy on the exchange, well below her $150-a-month target price.

"I would not even think about $50 a month," she said. "There's the what-if-factor: What if something really horrible happens."

Additional subsidies meant to limit cost-sharing for people with low wages would shred the $2,500 deductible that come with such plans to about $100 for the year--essentially turning a midlevel health plan to the proverbial Cadillac of health insurance.

Brian Caplener, 26 Bar-back, $25,000 a year

Many young people vacillated between buying and not-buying as they parsed the details of the new offerings for the first time, weighing price against the value and their perceptions of the utility of coverage.

Mr. Caplener expects to earn about $25,000 next year. His subsidy would be worth only $6 a month, meaning that the cheapest bronze grade offering would cost him $116 a month.

"It's reasonable in the sense that I have plenty of money to spend on things that aren't necessary," said Mr. Caplener, who works at Prost!, on Mississippi Avenue in North Portland. "I probably spend more than $120 a month going out drinking," he said.

But Mr. Caplener wanted to know what he could get for that price. The cheapest bronze-grade plan comes with an annual deductible of more than $5,000. A silver plan would run him at least $138 a month, or more, and come with a $2,500 deductible despite those subsidies.

"I couldn't afford to pay $120 a month, and if something happened, still have to pay $5,000," he said.

There are three main problems with Obamacare as it now stands;

1. We were told at the beginning that almost everyone's insurance premiums would drop if not at least stabilize, and that generous subsidies will be given up to a good income level. Then the message got switched that certain upper middle classes will have to pay more. Then it was the young subsidizing the old. Now the message seems to the young and healthy with incomes of barely $35K a year are expected to significantly subsidize their peers making $15K a year. Nearly all the young people 2-3 years were expecting a uniform decrease in their costs AND major subsidies for them.

2. In any case, trying to rely on those making ~$30K a year to prop up the system is folly. Paying $100 4-5 years ago was already a burden, now trying to pay $150-200 with a $5000+ deductible is even worse, and they get little to no subsidies whatsoever. The economy has not improved, wages are stagnant and many cases undergoing deflation, and its expected those people have plenty to spare?

3. Finally, the fatal flaw is that it assumes that merely slowing down the cost inflation, or perhaps somewhat stabilizing it, will patch up the healthcare system. Unfortunately, one ultimately needs a income of sorts in order to pay for any of those costs, no mater the level of subsidies or cheapness of the premiums. Even more unfortunately, as global economic forces and technological "progress" continues to ravage incomes and employment levels, the healthy core of payers will continue to decrease until this current Obamacare system is no longer tenable, because there will no longer be any sort of stable working/middle classes capable of paying even a modicum amount to float it.